5. Culture and everyday life

In general, there were many lines of continuity between the culture, everyday life and worldviews of the Late Middle Ages and those of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, many changes can also be identified, several of which were linked to the Lutheran Reformation. Because religion was omnipresent and intertwined with other aspects of Early Modern culture, hardly any sphere of life was left untouched by the Reformation. Concerning how the Reformation made its impact, and how changes were perceived by different people, many other factors were also at play, not least estate and gender.

The Lutheran state Church

With the Reformation in 1536, the king had taken over the Church’s properties. He now had overall responsibility for a number of tasks that had previously fallen under the remit of the Church, for example education and poor relief. The king also became the highest leader of the Church organisation itself, a position understood to be entrusted to him by God and which Christian III and his successors took very seriously. They had to defend the Church with the law and with the sword. Throughout the whole period, Denmark thus had a Lutheran state Church with the king as its head. This consolidation of the power of the monarchy – financially, politically and ideologically – was an important factor behind the development of a strong power state.

Luther’s distinction between a spiritual and a secular ‘regiment’ (often referred to as his doctrine of two kingdoms) is typically highlighted as one of the most important new ideas of the Reformation. According to Luther, there was to be a direct connection between the individual and God, and nobody else was to interfere in this ‘spiritual’ relationship. This did not mean that Church and state needed to be separate, however. On the contrary, as a matter of course the secular government regulated and protected the Church for the sake of the individual Christian, just as the clergy had to ensure that the population obeyed the government.

The new Lutheran Church was organised in a simple and uniform way. Unlike in the Middle Ages, when there had been powerful monastic orders and when the pope was the highest authority, there was now a straight line from the king to the bishops, whom the king appointed, further down to the rural deans and finally down to the pastors. In each diocese, the bishop supervised all the clergymen, but the rural deans played an important role as middle managers. A pastor could be responsible for one, two or sometimes three parishes. In most parishes, a parish clerk (degn) assisted the pastor with teaching children and a number of practical duties, including singing in church services.

Internal communication within the Church organisation took place through meetings or inspection visits by the bishop or rural dean. The 1537/1539 Church ordinance described how the bishop should monitor everything from the church building and the sermon to the parishioners’ knowledge of Christian doctrines. While the bishops had to conduct a visitation to all the churches in the diocese every three years, the rural dean had to pay an annual visit to all the churches in his deanery. In practice, however, such visits did not occur this often; on the smaller islands and in remote regions, many years might pass without one.

Between God and the Devil

The central role of the Church in culture and society was linked to the magical-religious ideas of the time. It was universally accepted that God had created the world and continued to intervene directly in the course of history, and that there was a constant battle between God and the Devil. Post-Reformation theologians rejected the belief in Purgatory as a separate stage, but the Day of Judgement and Hell remained central elements of the Christian universe. When Bishop Peder Palladius visited a church, for example, he threatened that, ‘there is a bailiff in Heaven who sees all hearts and knows all theft. He also has his executioner, the Devil in Hell, who will punish and torment you for it for eternity’.

Regardless of social rank, people shared the perception that they were part of a mutually binding community. A life of sin and contempt of God was thus not only a matter between the individual and God, but could also result in the punishment of society as a whole. When major disasters such as plague or war struck, pastors would often interpret them as ‘the wrath of God’. The king and the Church attempted to mollify this wrath on a number of occasions, especially during the Thirty Years’ War, by introducing collective days of prayer to appease God and by tightening punishments for ungodly behaviour. The idea was to cleanse society of all hardened sinners and practitioners of witchcraft so that they could not corrupt the rest.

Churches and rituals

Many of the churches in towns had been demolished after the Reformation. In Roskilde, for example, only three out of around twenty-one churches remained in 1550. In the rural parishes, in contrast, the churches stayed the same and the medieval mural paintings continued to adorn their vaults. It is a myth that the Reformation led to these being painted over. Much of the old material Church culture also remained in place, though side altars of the Virgin Mary and specific saints were gradually removed. New inventory was introduced, including larger pulpits and pews, so that the congregation could sit down during lengthy sermons. Near large manor houses, the nobility ensured that special family box pews were installed in the local parish churches, and in rural and urban churches alike, large tombstones and painted epitaphs were erected by the nobility, pastors or wealthy town merchants in order to honour God, decorate the church and ensure their own eternal remembrance. Churches thus functioned as places where power, social status and public ideals were communicated. It was not unusual for unrest and fights to break out in church, for example concerning who had access to which pews.

While the Catholic Church had seven sacraments, the Reformation reduced these to two: baptism and communion. Many rituals resembled the old traditions, however. Penance, for example, was no longer an official sacrament, but it was still necessary to go to confession before receiving communion. And, even though the last rites were officially abolished, individuals still needed to be prepared for death, by confessing their sins and receiving communion. Belief in the magical effect of the communion remained widespread, and people attempted to use the consecrated bread or wine as medication.

Uniformity and confession

The post-Reformation church service was a mixture of old and new. Although Latin still featured, Danish was now the main language of worship. Communal hymn singing in the vernacular was incorporated as a central element in the worship of God, and the pastor’s sermon now constituted the longest part of the service. The king and Church leaders worked to ensure greater uniformity in the country’s church services, partly through legislation and partly through the use of standard books, including the authorised Danish Bible (1550) and a common hymn book (1569).

Immediately after the Reformation, the king had sought to regulate printing as a medium. All printed books had to undergo censorship at the University of Copenhagen, and it was forbidden to import Danish-language literature from abroad. Printers were only allowed to work in the capital, and the king granted them privileges to ensure their loyalty, so that they primarily published ‘useful’ books. This was partly due to the experience of the turbulent Reformation years, and partly due to the continued confessional unrest in Europe. The king, the council of the realm and the bishops all wanted stability and ‘uniformity’ in the kingdom. For this reason, in 1569, Frederik II introduced twenty-five articles of faith for foreigners, as a kind of extended Lutheran creed to which all immigrants arriving in Denmark had to swear allegiance. Across Europe, different confessions were keen to distinguish themselves from one another.

The Lutheran parish clergy

After the Reformation, the parish pastor came to play a key role as a mediator between the state and the population. He was now an official of the Crown, representing the state at the local level. The Reformation had thus given the king control over a fine-meshed administrative and communicative apparatus that extended into every single parish. The parish pastor had to read out new statutes from the pulpit and was also obliged to submit local reports to the central administration. From 1645, all pastors had to keep church records in accordance with specific guidelines, with the aim of collecting more uniform information about the population.

The pastor was the shepherd of his flock, required to explain the Christian Gospel, to administer sacraments and rituals according to the new statutes and to interpret Luther’s teaching for all of his parishioners. In many places, change occurred slowly because most of the established pastors remained in their pre-Reformation positions, and it took decades before all clergymen had received Lutheran training. The parish pastor also served as the local expert; he knew Latin, owned books and often had an understanding of the art of medicine. He had to maintain a constant balance between old and new. For example, the bishops had to keep insisting that the parish clergy should not participate in the old tradition of processing over the fields with a cross in order to bless the coming harvest.

The Lutheran pastor should also preferably be a married man. Although priests in the Middle Ages had often cohabited and had children, it was only now that the parsonage became the official setting for a pastor’s family, as the ideal of the Lutheran household. Within a few generations, clerical families emerged, in which many pastors’ wives had been raised as pastors’ daughters and sons of pastors followed in their fathers’ footsteps. In this way, the clerical estate became increasingly self-recruiting.

The parish pastor and his family were the ideal of a pious Lutheran household. This painting is from the epitaph of pastor Søren Hansen Stenderup (from Skåne), his first and second wives and his many children (c. 1667). After the peace of Roskilde in 1658, like all his colleagues in the eastern Danish provinces, Søren became a pastor and official under the Swedish king. The epitaph hangs in Färlöv Church in Skåne, Sweden. Photo: Erik Fjordhede, livinghistory.dk

Marriage law after the Reformation

The Reformation’s rejection of celibacy for the priesthood meant that the monastic system of the Middle Ages had been abolished. It was therefore no longer possible to join a monastic community with other people of the same sex, although a few monasteries, such as the Bridgettine convent in Maribo, temporarily functioned as homes for unmarried members of the nobility. The good Christian life was now lived in this world, within a marriage and a family and through daily work. The regulation of marriage and sex had previously fallen under canon law, so there was a need for new legislation. The church ordinance only contained the outline of such legislation, but a detailed marriage ordinance was issued in 1582.

Divorce became possible in principle, because marriage was no longer a holy sacrament, but it was extremely rare in practice. The main focus was still on regulating sexuality. In Early Modern society, sex was only supposed to take place within marriage. Adultery for married people was classed as ‘fornication’ and was severely punished. Sex before marriage (known as lejermål) was also considered a sin, at least by the Church, in contrast to the medieval tradition in which betrothed parties could begin living together once they had promised themselves to each other. The clergy fought a long and often unsuccessful battle to make marriage in church decisive.

The Lutheran household

Early Modern society was fundamentally patriarchal, and Lutheran ideals did not immediately change this. People had to do their best wherever they were placed, according to their calling and their estate. This also meant that men and women had to carry out their duties as part of a household led by a pious ‘house father’. Important to Luther’s thinking was the doctrine of the three estates (trestandslæren), which supplemented the perception of society as divided into function-determined estates (nobility, clergy, burghers and peasants). Luther’s doctrine of the three estates centred on ties of reciprocal obligations in a Christian society. The three estates were the state, the Church and the household. The state had to protect its subjects, who in return would obey the authorities. The Church (clergymen and teachers) had to educate the rest of society, including kings and the nobility, who in return had to listen and learn. And the household, which was the basic unit of society, received protection and education in return for their obedience and work.

Within the household, there were similar bonds of reciprocity. The male head of the family had to take care of his wife, children and servants in return for their obedience. Children had to obey their parents, who were correspondingly responsible for their care and upbringing. And the servants had to obey the master and mistress of the household in return for shelter, food and protection. Luther’s ideas about the household could be read in his ‘table of duties’ (hustavlen), which was a section in his Small Catechism and – as such – part of the Christian doctrines in Lutheran Denmark that were taught to children, addressed in sermons and referred to in laws and religious literature

The fight against sin and witchcraft

In an effort to establish a Christian society in which sin was combatted and ‘true godliness’ strengthened, the king and the council of the realm issued a number of regulations of a ‘social disciplining’ character. This occurred in particular after the orthodox Lutheran Hans Poulsen Resen became bishop of Sjælland and one of the king’s most senior advisors in 1615. As part of a group of statutes issued in 1617, the centenary of Luther’s theses and thus the beginning of the Reformation, it was decided that sex before marriage should result in a public confession in front of the congregation and in the punishment of both the man and the woman by the secular courts. Sin was thus criminalised. Further regulations followed in a major Church statute in 1629.

Another important statute issued in 1617 concerned witchcraft, the existence of which nobody questioned. For the vast majority of people, the practice of magic was not a problem as such; in local communities, people were usually content if a wise woman or man could bless or exorcise and thus cure sick animals. The danger only arose when such skills were used with malicious intent. If a woman wished harm on somebody and such harm occurred, this was taken as evidence of witchcraft – and the woman was viewed as a witch.

According to the Church, however, ‘white’ and ‘black’ magic alike – that is, both healing and harmful magic – were the Devil’s work. Irrespective of their intentions, people should not manipulate magical forces; if they did, they would become servants of the Devil. Many clergymen wrote about the phenomenon and warned against deals with the Devil, for example, and witches’ sabbaths. It was usually women who were portrayed as witches and accused in local communities. They were seen as the weaker sex, who could be more easily tempted. On a concrete level, women probably resorted to verbal threats more often, while men used their fists.

In the statute ‘against witches and their accomplices’, issued in 1617, white magic was criminalised and it was stated that those who practised black magic should be burned at the stake. Over the following decades, witch burnings took place across the entire country, but the phenomenon began to decline from around 1650. Some of the noble judges at the provincial courts grew increasingly sceptical, and a number of cases ended with acquittals. There was now the risk that women accused of witchcraft would return to their parish and sue their accusers for defamation. The financial costs involved in such cases also contributed to fewer accusations. In total, approximately 1,000 people were burned, and 80%–90% of these were women. The last witch burning took place in 1693, but belief in witchcraft and witches continued.

Christian teaching and literacy

Just as sin had to be fought, the good had to be promoted, and it was with this idea that children’s upbringing came into the picture. As a rule, this was the parents’ responsibility; children were socialised and educated in their own households according to their gender and estate. Boys accompanied their fathers in the field or the workshop while girls helped their mothers, and the children of the nobility and clergy were raised and educated at the manor houses or parsonages respectively, separate from the lower estates. As early as the age of ten or twelve, many children from ordinary backgrounds started work as servants or apprentices, and they therefore had to join a new household and answer to a new master and mistress.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was not compulsory for children to attend school, but the Church ordinance required that all children should be raised according to Christian teaching (den kristne børnelærdom), which was now made synonymous with the content of Luther’s Small Catechism. The parish clerks were given special responsibility for this teaching, and the pastor had to check young people’s knowledge before their first communion, typically when they were sixteen or seventeen. According to the rules, insufficient knowledge should result in exclusion from communion and thus from the right to be betrothed or to take over a tenant farm, and other aspects of adulthood. The clergy became increasingly keen to promote instruction in reading as a means to make teaching more effective.

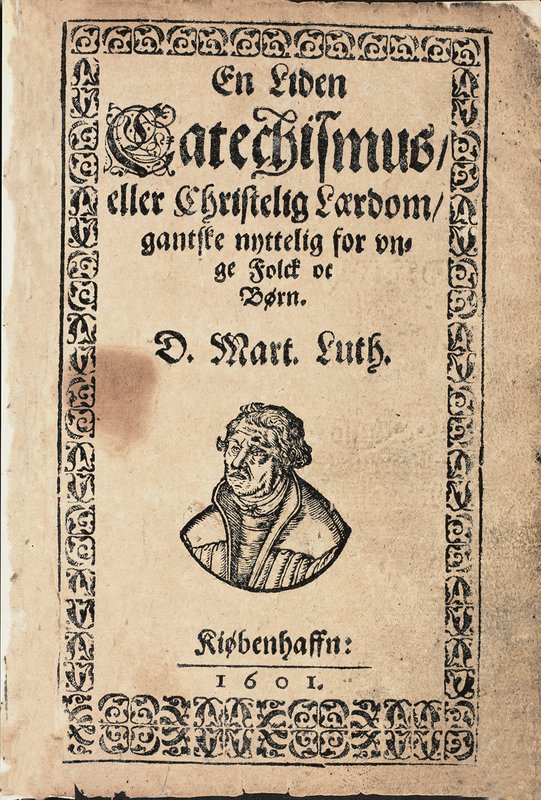

Title page of A Small Catechism (En Liden Catechismus) from 1601. Luther’s Small Catechism was likely the period’s most widespread text, not least because it served as a reading book and textbook for all children. It consisted of five main sections (the ten commandments, the Lord’s prayer, the creed, baptism and communion), which were all accompanied by Luther’s explanations, prayers and additions, such as the table of duties (hustavlen), in which he explained how to live as a good Christian in society. Photo: ProQuest/Royal Danish Library

Permanent school buildings were erected in some places, but as a rule schooling simply took place wherever a willing teacher could be found. This was the case almost everywhere, since an increasing number of men and women had learned to read themselves and could therefore teach the basics with the help of printed primers and catechisms. An entire hierarchy of different reading and writing schools arose. Children first learned to read printed texts in the vernacular; once they had learned to read, they could better learn the full catechism and other texts by heart, guided by the parish clerk. Many children, especially girls and most of the poor, never made it any further. Learning to read handwriting, to write and to calculate required more schooling and higher fees. It was mainly boys who reached this level, provided their parents were willing and able to pay. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, written culture had continued to expand, especially in the towns. Several types of reading material were available – religious literature, almanacs, small stories and broadsheets with news and ballads – and an increasing number of people kept accounts and wrote letters.

Latin schools and university

Some boys also went to a so-called ‘Latin school’ (latinskole) or grammar school. These were a continuation of medieval Church schools. According to the Church ordinance, in order to ensure its quality, there should only be one Latin school per market town, in addition to schools for reading, writing and accounting. The Latin school had a double purpose: to provide education and general support for poor boys (who, as pupils, were allowed to beg and earn money from singing at funerals), and to provide the most talented with an education in Latin and religion, so that they could serve the Church. In the smaller towns, Latin schools were primarily filled with poor boys who learned to read and to master beginner’s Latin, while in the larger cathedral towns, Latin schools were divided into six or seven grades according to the pupils’ levels, so that both Latin and Greek could be taught in the upper grades. Pastors’ sons gradually started to fill the school benches in the higher grades, but for a long time Latin schools were one of the most important means of social mobility for the academically gifted sons of peasants and craftsmen.

If students wanted a career in the Church, the next stop was university. The University of Copenhagen re-opened in 1537, modelled on Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon’s university in Wittenberg. Theology was by far the most important subject, and the theology professors constituted a particular group who also served as official censors and sometimes as an expert committee in legal matters, for example in cases of demonic possession. Some professors also practised subjects such as medicine and astronomy, based on an understanding that, in addition to the Bible, one should also study nature as God’s creation, guided by faith.

Renaissance scholars and cultural developments

Learning was also cultivated outside the university. In Nordic history, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are often referred to as the Renaissance Period. ‘Renaissance’ means ‘rebirth’; it refers to a movement in science, art and culture that began in fourteenth-century Italy and later spread to large parts of Europe. The Renaissance movement venerated Antiquity and humanity’s privileged place in creation, and its followers sought to revive ancient values following the Dark Ages, as they were now called.

In addition to influencing architecture and art, the ideals of the Renaissance manifested themselves in a great interest in science, language and history. From the end of the fifteenth century, a particular type of Biblical Humanism arose, which was concerned partly with studying biblical texts in their original language and partly with the trans-lation of these texts into the vernacular. Christiern Pedersen combined both these interests. He published Saxo’s historical chronicle Gesta Danorum in 1514 and was behind the first complete translation of the Bible into Danish in 1550.

History writing was of particular interest to the monarchy. The history of the kingdom needed to be told, not least to take up the ideological battle against Sweden and to highlight the history and legitimacy of the Danish monarchy. Hans Svaning and Anders Sørensen Vedel, among others, managed to collect extensive materials and begin the project, but did not deliver a full manuscript. Instead, a learned councillor of the realm, Arild Huitfeldt, took on the task and wrote a Danish-language history of Denmark. It was designed to serve as a model for the young Christian IV, and particularly to show how wrong things could go if a king failed to collaborate with the nobility. During the seventeenth century, the king’s historiographers succeeded in completing a history of Denmark in Latin.

Parsonages and manor houses could also house historical, literary and theological studies. Small groups of young noblemen gathered to study at Rosenholm Manor, the home of Holger Rosenkrantz ‘the Learned’. Noblewomen were also intellectually active, especially in collecting medieval ballads. It is not without reason that the period has been referred to as the ‘learned period’. Members of society’s elite were part of two cultural spheres: a more learned and exclusive culture, and a wider ‘popular culture’. In both rural and urban communities, rich cultural traditions existed with regard to storytelling, singing, dancing and performing. Many of these had roots in the Middle Ages, and were only partly changed or modified by new religious and political developments.

♦ From the Reformation to absolute monarchy

The period 1523–1660 began with political unrest, the Reformation movement and, eventually, civil war. In 1536, the victorious Christian III was able to implement the Lutheran Reformation and thus establish important foundation for the following decades.

The Reformation meant a break with the papal Church and the introduction of a national, Lutheran state Church headed by the king. This strengthened the power of the state. Bishops, rural deans and pastors were now royal officials, and the king’s power was increased by the takeover of Church land. Responsibility for a number of social functions that previously fell to the Church now came to lie with the king, including areas such as education and poor relief, though the consequences

of such changes would mainly take effect in the longer term. The Reformation also resulted in a number of changes to church ceremonies and devotional life. The monastic system and the worship of saints were abandoned, while the new Lutheran clerical family emerged as the model to emulate.

Another central theme was the dominance of the nobility as the exclusive elite of Danish society. At the beginning of the period, this estate achieved a monopoly as a ruling estate with the exclusion of the clergy from the government. As a landowning estate, the nobility was also able to take advantage of favourable agricultural conditions in the second half of the sixteenth century and the early decades of the seventeenth century. However, the many wars of the period, not least from the 1640s onwards, put a stop to this development.

The period was further marked by the emergence of a military-fiscal state. The wars with Sweden led to the destruction and surrender of large areas of land, including the definitive loss of the Skåne provinces in 1658, and the rapidly increasing cost of the military resulted in a fast-growing state budget. As the income from the king’s crown lands was no longer enough to fund the wars, an increasing amount of money had to be raised through taxation. This change posed a threat to the nobility’s position, as it meant that their traditional role as defenders of the realm was assumed by a royal army. On several occasions, the nobility attempted to curb taxation and to gain control of the army, but they were only partially successful, and the defeat to Sweden in 1657–1658 ended up as a political defeat for the Danish nobility. Because of this, in 1660 Frederik III was able to carry out a coup in which the old order of elective monarchy and coronation charters was discarded and a new political system introduced: absolute monarchy.