1. From the Middle Ages to the Reformation and the Early Modern Period

In European and Danish historiography, the time around 1500 is traditionally viewed as a landmark – the end of the Middle Ages – around which many epoch-making events occurred. Particularly significant were the European discoveries of America and the sea route to India, which were followed by an intensification of global contacts and, subsequently, colonisation in all parts of the world. Other important developments were the religious reformations that took place in Germany and other European countries, which led to the break-up of the old medieval Church under the leadership of the pope and to the creation of a confessionally divided Europe with Lutheran, Calvinist and Catholic regions. A marked strengthening of state power in most countries can be viewed as another good reason to speak of a new period in the history of Europe. Moreover, in a Danish context, it was from around 1500 that the Renaissance began to make its mark on art, architecture and science.

The development towards a stronger central state had begun in the Middle Ages and was intensified in northern Europe by reformations, in which kings and princes took over ecclesiastical estates and gained responsibility for the reformed Churches. This resulted in increased resources, new powers and stronger legitimacy. The military and political developments of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries contributed further to the emergence of what has been called the ‘military-fiscal state’ or simply the ‘power state’ (magtstat). The spread of print media and the establishment of new human-centred paradigms in science and the arts are further reasons to view 1500 as marking the beginning of a new era. In European historiography, c. 1500–1800 is usually referred to as the Early Modern Period, which began with the above-mentioned events and ended with early industrialisation and the French Revolution in 1789.

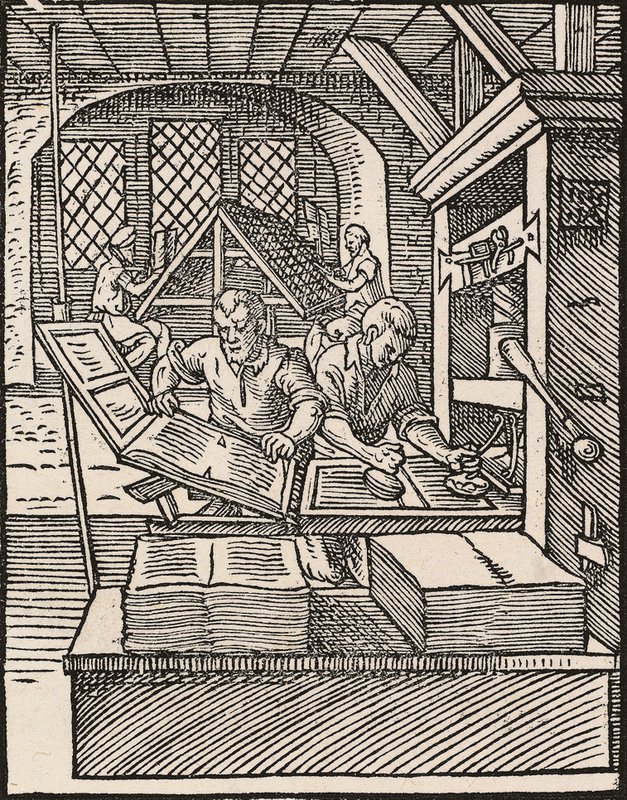

A new printing technique was invented by Johann Gutenberg in Germany around 1440. With strong and movable lead type, durable ink and an effective press, it was now possible to quickly produce thousands of identical copies of the same text. However, handwritten books continued to dominate for a long time, and the first printed books resembled the handwritten ones. Woodcut from 1568 by Jost Amman (1539–1591). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Denmark, Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands

During the Early Modern Period, successive Danish kings ruled a conglomerate state made up of a number of provinces and territories. This state was geographically vast, but sea transport helped to connect the different realms and territories and, as such, brought together areas that would otherwise have remained distant. The core consisted of the kingdom of Denmark, which, at the beginning of the period, stretched from the Jutland peninsula in the west to Skåne, Halland and Blekinge in the east. Norway remained under the Danish crown after the collapse of the Kalmar Union in 1523. Christian III’s coronation charter from 1536 included a section stating that Norway was to be regarded as a Danish province and that the Norwegian rigsråd (council of the realm) should be abolished. In reality, however, Norway continued to be treated as a separate kingdom with its own legislation and a number of particular institutions, which, from 1572, included a statholder (governor-general). The country was of great importance owing to its size and its wealth of natural resources.

Control over Norway also brought with it control over the Norwegian dependencies: the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland. There was virtually no contact with Greenland between the fifteenth century and the 1720s, but Iceland and the Faroe Islands were important for trade, sailing and fishing throughout the entire period. A strong writing culture had existed in Iceland since the Middle Ages, and after the Reformation the Bible was translated into Icelandic, which became the language of the Church, schools and local administration. On the Faroe Islands, in contrast, the official language for these three spheres was Danish.

The duchies and Nordic power relations

The Danish king’s role as duke of Schleswig and Holstein was important for his position. These two duchies had been the subject of inheritance division in the Middle Ages because they were seen as belonging to the royal family’s estate. In 1544, Schleswig and Holstein were again divided, this time into three parts under separate princes. Further divisions followed this. After 1580, the region generally fell into three parts: the area under the control of the Crown; the areas under the duke of Gottorp; and the noble manors, which were governed jointly by the king and the duke. Certain issues, including most defence matters until 1658, also fell under this joint governance. The duchies constituted an important economic and political resource for the king, as he was independent of the Danish council of the realm in these regions. This was something that Christian IV in particular used to his advantage.

Most of the population in Holstein and parts of southern Schleswig spoke Low German, while the rural population in central and northern Schleswig were predominantly Danish-speaking. Frisian was spoken along the west coast. German (High and Low) was dominant in the towns, and the language of the administration was also generally German for the entire period. The duchies functioned as an important cultural corridor for the currents from the south, and many craftsmen, merchants and courtiers in Denmark had emigrated from these regions.

The Nordic region was divided into two spheres of power throughout the entire period: Denmark-Norway and Sweden-Finland. The two sides were both ideologically and militarily armed from the middle of the sixteenth century, which led to several wars, and, in 1658, all of the eastern Danish provinces had to be ceded to Sweden. At the beginning of the period, Copenhagen was situated in the middle of the Danish realms and territories, but from 1658, the capital was located in the most easterly part of an amputated state. Since Denmark lay at the entrance to the Baltic Sea, other European powers regularly intervened in the Danish–Swedish balance of power.

Map of the areas that Denmark-Norway ceded to Sweden as a result of the Swedish wars. © danmarkshistorien.dk

A society of privileges and estates

This module has three main themes: Denmark as a society of privileges and estates; the emergence of a so-called ‘military-fiscal state’; and the consequences of the Reformation. Central to the first theme is the role of the nobility.

Together with the king, the small elite of noble families (0.2% of the population) had the exclusive right to own agricultural land, which was society’s most important means of production. During the period, the nobility succeeded in maintaining and expanding its political, economic and social rights through a system of privileges that defined what all of the estates – including the clergy, the burghers and the peasantry – could and could not do. Regardless of which aspect of societal development is explored, it is important to keep in mind that society during this period was made of up of estates with fundamentally different rights and resources, with a privileged nobility at the top.

In older Danish historiography, there is a strong tradition of referring to the period 1523–1660 as the ‘golden age of the nobility’ (adelsvældens storhedstid), when the power of the nobility reached its zenith. According to this tradition, it was only in the following period that the monarchy could free itself from the nobility by introducing absolute rule. However, recent research has placed more emphasis on collaboration and negotiation between the king and the nobility, as well as on the multiple functions performed by the noble estate.

The growth of a military-fiscal state

The second theme in this module concerns the wars of the period and their significance for a different – and stronger – mode of state formation. The six wars in the period 1563–1660 resulted in an explosion in state expenditure, which had to be financed through dramatic tax increases, also during peacetime. This development resulted in radical changes to the administrative and state apparatus, which became a type of ‘military-fiscal state’ – also called a ‘power state’ – and ultimately a new political system, namely an absolute monarchy.

The dynamics behind the growth of a power state became a key topic for historians during the last decades of the twentieth century. Previously, research had centered on the strengthening of the king’s power at the expense of the nobility. However, in more recent research, historians have placed less weight on the king and the nobility as competitors and concentrated instead on the changes to state power itself, including the growth of the administrative apparatus and the state budget.

The impact of the Reformation

The third main theme in this module centres on the impact of the Reformation. The Reformation movement and the new Reformation order from 1536–1537 led to short- and long-term changes. A number of specific changes to the liturgy and the Church’s organisation were visible from the outset, as were the practical consequences of the king’s acquisition of Church land. But there were also more gradual changes to religious beliefs and practices, and to the way people viewed gender roles, the family and the upbringing of children.

Traditionally, historical research on the Reformation has consisted of two relatively separate strands: a Church history strand emphasising the religious ideas and the restructuring of the Church itself, and a political-historical strand examining the Reformation’s significance for the power struggles between the nobility and the king. In more recent research, however, a broader concept of the Reformation has been introduced, according to which it is seen as part of wider social and cultural historical changes. Historians are also increasingly viewing the Reformation as a transnational phenomenon, placing developments in Denmark into wider European contexts within which different confessional cultures emerged. Finally, the Reformation is now more often understood as a protracted and complex process, as opposed to a complete and predefined theological programme that could be introduced quickly ‘from above’ based on Luther’s ideas.

Since the turbulent Reformation years between 1523 and 1537 mark the beginning of the period discussed in this module, it is worth outlining some of the main features and events of Danish Reformation history.

The preconditions of the Reformation

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, everyone lived with a magico-religious worldview. They understood their own existence and society’s composition in the light of biblical narratives, and it was widely believed that the Day of Judgement was approaching. The Church, monasteries and clergy were essential mediators between God and the individual, and many people participated in religious ceremonies and devotional life in connection with ecclesiastical institutions. This meant that any criticism of the Church’s teaching and legitimacy concerned not only theology and internal ecclesiastical affairs, but also social and political conditions and the norms that bound society together.

Criticism of the papal Church had been voiced since the late Middle Ages, along with a demand for ‘reformation’ – a restoration of the Church so that it could return to its original and true foundation. This occurred in connection with the Biblical Humanist movement, which emphasised the importance of the word of the Bible, and with Conciliarism, which advocated increasing the authority of the general Church council, or synod, for all parts of the Catholic Church. Such criticisms were directed particularly at the pope in Rome and his cardinals and bishops. Many interpreted the clergy’s ‘abuse’ of their position and other signs of crisis as tangible expressions of the imminent advent of the Day of Judgement. Meanwhile, in European towns, as print culture and literacy became more widespread, an increasing number of people could read biblical texts and critical works for themselves. During the decades preceding the Reformation, social tensions and political power struggles also contributed to a state of crisis in many places.

Luther’s teachings

When the monk Martin Luther published his ninety-five theses in Wittenberg in 1517 and criticised the Church’s trade in indulgences, neither he nor his contemporaries could have predicted that it would mark the beginning of the division of the old Church. Within a few years, however, an open and radical critique of the dogmas of the old Church was growing in strength. News of Luther’s challenge to the papacy and of the German Peasants’ War (1524–1526) spread throughout Europe, as did the writings of Luther and other reformers. Such news could travel quickly and efficiently because of the printing press.

Reformation ideas addressed a number of issues. The central message was that the Church should not stand between God and the individual. God alone could ensure the sinner’s grace and salvation. According to the reformers, the trade in indulgences, which were intended to shorten one’s time in Purgatory, was a human invention, just like monasticism, pilgrimage and the worship of saints. What mattered was faith, not deeds. Everybody should have direct access to God’s word, and it was therefore important that the Bible was translated and that pastors could deliver their sermons in the vernacular. Only the sacraments used by Jesus in the Bible (baptism and communion) should be recognised, and, at communion, bread and wine should be available to all believers, not just the priests. Bishops and priests would no longer be required to be celibate, because they were not seen to occupy a particularly holy position. Instead, Luther underlined the importance of obeying the secular authorities appointed by God.

A princely reformation and several urban reformations

Frederik I’s coronation charter from 1523 declared that the king was not to allow ‘any heretics, Luther’s disciples or others’ to preach against the Church and its teachings. Only a few years later, however, in 1526, the Carmelite monk Poul Helgesen, who had himself read and translated some of Luther’s works, described how ‘the poison of Lutheranism was creeping through the whole of Jutland’.

In the district of Haderslev in the duchies, the Reformation was imposed ‘from above’ by the ruler, Frederik I’s son Christian, between 1526 and 1528. A passionate supporter of Luther, Christian introduced a Reformation order in Haderslev, which included evangelical services, a pastoral seminary and the abolition of celibacy.

The movement also gathered momentum in many Danish towns. In Viborg, the Johannite monk Hans Tausen, who had studied in Wittenberg, began preaching ‘according to the Gospels’ in 1525, and was therefore excluded from his monastic order. He obtained special legal protection from Frederik I. Soon after, a seminary was founded and a German printer set up a press in Viborg. By 1530, the Reformation was visible to all in Viborg: the monasteries had been shut and the monks driven out, twelve churches were closed, a new liturgy was introduced and the first pastors had got married. A similar urban reformation took place from 1527 onwards in Malmö. At this stage, ‘Lutheran’ was an insult used by opponents of the Reformation, and the preachers referred to themselves as ‘evangelicals’. Danish reformers were inspired not only by Luther himself but also by different reformation trends, including some southern German and more radical movements. Among other things, this found expression in attempts to undertake an immediate reformation of society with the Bible as a guiding principle.

Political divisions and civil war

Frederik I had to strike a fine balance between the powerful, Catholic-dominated council of the realm and the more pro-Reformation forces. It can be assumed that he was positively disposed towards the new trends, as he had two daughters married to Protestant German princes. First and foremost, however, he was a pragmatist who wished to retain power in a difficult situation; there was unrest among the peasants and the deposed Christian II presented a constant threat from his exile in the Netherlands.

1526 was a pivotal year. At an annual assembly of the council of the realm in Odense, Frederik persuaded council members to accept that the appointment of bishops and high ecclesiastical officials no longer required approval from the pope in Rome. In this way, the Danish Church became a de facto territorial or national Church. In the following years, tensions and antagonisms escalated, and, in 1530, a violent iconoclastic attack took place in the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen, resulting in the destruction of several Catholic altars and paintings. In 1531, the exiled king Christian II arrived in Norway with troops, supported by his brother-in-law, the Holy Roman emperor, Charles V. Christian II was only partly successful, and negotiations were initiated between him and the new government. Christian was promised free passage, but, instead, he was sailed to Sønderborg Castle and imprisoned. On Fyn, the evangelical-minded bishop carried out the first reformation of an entire diocese in 1532.

Frederik I died suddenly in the summer of 1533, and the council of the realm was paralysed. For the majority of the council, the king’s eldest son, the Lutheran duke Christian, was not an acceptable candidate for the throne, while his younger brother Hans was only twelve years old. A majority in the council managed to postpone the royal election, and the Catholic bishops sensed an opportunity to impede their opponents. Hans Tausen was summoned to the council and charged with defamation and heresy by the bishops. No judgement was passed, however, and it soon became clear that the country could not be ruled without a king.

The following years were characterised by discord and civil war. Long-term dissatisfaction and unrest among the peasantry regarding the bishop’s tithe and other taxes led to a rebellion in northern Jutland, called Clement’s Feud after its leader, Skipper Clement. Manor houses were set on fire and there were also uprisings in several towns. The rebels received support from the Hanseatic city state of Lübeck, and a commander was appointed, Count Christopher of Oldenburg, who was supposed to seize power on behalf of the imprisoned Christian II. It was for this reason that the civil war came to be known as the Count’s Feud. Eventually, the majority of the nobility had to conclude that Duke Christian (III) was the only acceptable candidate for the throne, and he was proclaimed king in 1534. A campaign was launched with Commander Johan Rantzau leading the duke’s troops. He first conquered Jutland and Fyn, after which, following a long siege, he managed to force Copenhagen to surrender.

Reformation and the Danish Church ordinance

Following urban reformations that took place ‘from below’, the turbulent Reformation years in Denmark ended with a Lutheran reformation imposed ‘from above’. Christian III had already imposed a reformation in Haderslev, and he now wished to reform the entire Danish realm. With his army behind him, Christian III had the Catholic bishops imprisoned, and, on 30 October 1536, a treaty was issued announcing that the king was now the head of the Church and had taken over the Church estates with immediate effect.

The ideal Lutheran church service with sacraments is shown here on an antependium from 1561. On the left is the baptism and in the middle is the communion, where the two clergymen give out both bread and wine to the parishioners. On the right, the pastor preaches to the congregation on the basis of the Bible, and, as the important background, Christ on the cross can be seen. The painting is from Torslunde Church, near Roskilde, but is now part of the collection at the National Museum of Denmark. Photo: National Museum of Denmark

It soon became clear that a Reformation ordinance based on the Wittenberg model was required. Christian III corresponded with Luther himself, and not long afterwards one of the latter’s chief advisers, Johannes Bugenhagen, came to Copenhagen. He arranged the coronation of the king and queen in the city’s main church and prepared a new Church ordinance together with royally selected experts, including the young Peder Palladius, who had studied in Wittenberg.

A new Church ordinance was issued in Latin in 1537 and in Danish in 1539. This document acted as a kind of constitution for the Church for approximately a hundred and fifty years and in practice for even longer, since most of its provisions were included in subsequent legislation. Having acquired the Church’s properties and institutions, the king assumed responsibility for several societal functions that had previously been carried out by the Church, such as worship, education and poor relief. Bugenhagen was also the driving force behind a new foundation for the re-opened University of Copenhagen, which had been closed during the turbulent Reformation years. This was where future Lutheran clergymen were to be educated.

The formal conditions for a successful reformation were now in place, but the major task of re-organising the Church and state administration – and not least of building a Christian evangelical community – still lay ahead.

The Influence of the Reformation on Society and Culture

In this film, Charlotte Appel discusses the significance of the Reformation on society and culture in Denmark. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose ' English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.