4. The Crown and the nobility

Besides the king, there was only one group with real political power after the Reformation: the nobility. In older historical research, the political system of the period is referred to as adelsvælden (‘noble rule’), in contrast to the enevælde (‘absolute monarchy’) that followed, but the former term is misleading. It is instead more accurate to speak of ‘diarchy’ (two-part rule), in which the king and the nobility shared control of a strengthened state. However, the period came to be characterised by a gradually more intense power struggle, which ended with the king assuming complete political control.

Kings and the monarchy after the Reformation

The centre of power was the king himself. He allocated the Crown’s revenues, he appointed people to many different positions and he made decisions on countless issues on a daily basis. But the king’s power was limited, especially by his obligation to refer important issues to the council of the realm, which also elected kings. After Frederik I’s death in 1533, the country was left without a king, but when civil war broke out, the council of the realm assembled and elected the deceased king’s eldest son. It was difficult to manage without a king, especially during a time of crisis.

Christian III was deeply religious. Having secured the crown and implemented the Reformation, he worked for the rest of his life to consolidate both. In 1536, he had his son Frederik (II) appointed his successor by the council of the realm. This was an expression of strong royal power, where the council’s right to vote was not abolished but weakened in favour of the king.

In the years following his succession in 1559, Frederik II was preoccupied by the rivalry with Sweden, but after the Seven Years’ War, he became interested in more internal issues. As a young man, he had fallen in love with the noblewoman Anna Hardenberg, and many years passed before he finally bowed to tradition and enormous pressure from the women in his family and married a princess in 1572. For this reason his son Christian was only ten years old when Frederik died in 1588. Christian had already been appointed successor, and upon Frederik II’s death the council of the realm installed a noble regency government, which managed the country until Christian IV came of age in 1596.

Christian IV’s reign came to last over fifty years and was marked by great ambitions. He built new palaces and founded new towns to strengthen trade and other urban enterprise. He also tried (and failed) to achieve a leading role for Denmark in northern European great power politics. Just like his own father, Christian appointed his eldest son Christian to be his successor. However, Prince Christian died shortly before his father, and there was therefore no appointed successor to the throne when Christian IV died in 1648. Although there was just one serious candidate – the only surviving son of the king’s royal marriage – the situation gave the council of the realm an unusually strong negotiating position, which came to set the conditions for the new king, Frederik III.

Demonstrations of power

After the Reformation, successive Danish kings were keen to demonstrate their royal power. Christian III had already begun to build new, larger palaces that were more representative of his power. This trend continued under Frederik II, who built Kronborg Castle, but reached its first peak under Christian IV, who built Frederiksborg and Rosenborg. The palaces were clear expressions of the king’s power and position, not only in their size but also in their magnificent decoration and artistic design, which included motifs from both Antiquity and Danish history. In this way, the kings signalled that they were part of a European tradition but also that Denmark had a glorious past. A large number of people, including many nobles, gathered at the king’s court. The court was a place where the king’s power was continuously visible, and also where people could acquire their own power by forging contacts and obtaining favours.

Christian IV had his portrait painted many times, with different staging. This painting combines depictions of the king and Queen Anna Catherine. The focus is on the king as a powerful ruler as well as symbols of warfare, wealth and courtly extravagance. Painted by Pieter Isaacsz (1569–1625), 1612. Photo: Royal Danish Collection, Rosenborg

The state also came to support other cultural projects, which were aimed at strengthening its reputation and prestige. The astronomer Tycho Brahe received large sums from Frederik II and the regency government, and royal historiographers were employed to write the country’s history. A large number of foreign architects and artists came to the country to build and decorate palaces and to paint both the king and members of the nobility.

The noble council of the realm

The king’s main political partner, and opposite part remained the council of the realm (rigsråd). After the Reformation members of the clergy were no longer included, and thus the council was greatly reduced; it usually consisted of around twenty members of the nobility. Just as the council of the realm elected the king, the king appointed the individual members of the council. The king did not have complete freedom to choose: as a general rule, he selected from among the wealthiest and best educated, and from the families who were already influential. Once appointed, councillors usually served for life, just like the king himself. This gave both parties an important independence.

In principle, the council of the realm had tremendous power. In addition to electing the king, it had to approve new taxes and important legislation, and the king could not go to war without its permission. This was set out in the coronation charter (håndfæstning) the king had to sign before he could be crowned. However, in reality, the power of the council was diminished by the fact that it only assembled once or twice a year. Rather than setting the agenda itself, its power consisted in approving, slowing down or rejecting the king’s initiatives. Another limitation was the council’s lack of influence on the governance of the duchies.

Officers of the state and central administration

The intermediaries between the king and the council of the realm were the officers of state (rigsembedsmænd), who were both the king’s foremost advisers and the leaders of the council. The rigshofmester or steward of the realm was the highest ranking amongst them, but this position was vacant for long periods of time, as was the position of marshal of the realm (rigsmarsk), who was chief military officer for the noble forces. The position of chancellor of the king, who was head of the main administrative office, the chancellery, was almost always filled. The first chancellor after the Reformation was Johan Friis, who managed to serve three kings.

The chancellery was the most important office in the central administration, since it received the king’s correspondence and prepared replies. It took care of matters involving Denmark, Norway and the dependencies, as well as correspondence with Sweden. The chancellery was known as the ‘Danish chancellery’, because its working language was Danish. There was also a German chancellery, which handled matters involving the duchies and correspondence with most of the rest of the world. The working language here was German. A third government office was the treasury (Rentekammer), which was responsible for financial administration. The Danish chancellery was staffed by members of the Danish nobility, while the German chancellery and the treasury (although led by noblemen) were primarily staffed by officers from the burgher estate.

The central administration was not overly large – perhaps fifty people in total – and formed only a small part of the court. However, it was a significant development that a central administration existed at all. More issues than previously were presented to the king for decisions, and, across the country, the king’s people had to keep accounts that were centrally controlled.

The len administration and royal stewards

As in the Late Middle Ages, the Crown’s property and power at the local level were still managed by members of the nobility in so-called len. There were several kinds of len. Some of them, referred to by Danish historians as hovedlen, were districts with general administrative authority over one or more hundreds (herreder; singular herred) and management responsibility for some of the Crown’s estates in the area. The main districts or hovedlen usually had a castle as their centre, and, since the king now owned the castles of the former bishops, he had more castles at his disposal than before. The other minor len only included Crown estates, many of them former episcopal or monastic estates.

The royal steward, the lensmand, was responsible for the entire district administration, which included financial, legal and military matters. He was also responsible for collecting the income from all the properties in the districts. He could either send a fixed sum to the king and keep the rest, or submit accounts and receive a fixed sum himself plus a percentage of some of the variable revenues. Owing to the growth of the central administration, which could now keep track of the accounts, the latter practice generally became more common.

Holger Rosenkrantz (1574–1642), whose epithet was ‘the Learned’, was an unusual mix of nobleman and intellectual. He was born into a wealthy noble family, married the equally wealthy Sophie Brahe, and, from a young age, prepared himself for a career in the king’s service. Between 1616 and 1627, he was both a royal steward and a councillor of the realm. For long periods of his life, however, he preferred theological studies, and for a number of years he ran an academy of sorts for young noblemen and burghers at his manor Rosenholm. In 1627, he voluntarily left the council of the realm in order to concentrate on his intellectual activities. Painting from 1636. Photo: Hans Petersen, Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle

The position of royal steward was attractive; it offered income, influence and prestige. As such, it was an important part of the king’s power that he appointed and dismissed the royal stewards. He was obliged, however, to appoint them from the ranks of the Danish nobility. During the period explored in this module, the number of len decreased. This was economically advantageous for the king, since the smaller len made only a modest profit once the royal steward had taken his share, but it also meant that there were fewer attractive positions for the nobility, so the competition for the len intensified. The political and economic elite fared best in this competition, which in turn exacerbated the disparities between the members of the noble estate.

State Church and Power State

Watch this film in which Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen talks about the strengthening of the Danish state power and the development of the military. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The judiciary and social disciplining

Upholding the law required a balance of power from above and below. Most cases were heard in the local hundred court (herredsting), where peasants still served as jurors and official witnesses. The hundred court was led by the bailiff, who was appointed by the royal steward. Well into the seventeenth century, most bailiffs were peasants, who judged on the basis of their practical experience and a certain degree of legal knowledge. The towns had their own council courts (rådstueret) and town courts (byting) with town bailiffs.

Above the rural and urban local courts were the provincial law courts (landsting), which were led by noble judges. These courts functioned primarily as appeal courts, but important cases could be referred directly to the provincial courts. The highest court in the country was the king’s court of final appeal, which consisted of the king and the council of the realm in association. Criminal cases against the nobility had to be brought directly to this court.

The judiciary was given new tasks when the state introduced something that modern historians have dubbed ‘social disciplining’. This meant encouraging people to change their behaviour in certain areas of life, such as sex outside marriage and violence. Great progress was made in reducing violence throughout the period. Over the course of the seventeenth century, the number of homicides in relation to the population fell significantly, to less than a tenth of the previous level, and thus to a level similar to that of twenty-first-century Denmark.

Administration of Norway and the duchies

In connection with the Reformation, the Norwegian council of the realm was dissolved. The Danish council of the realm assumed power over Norway, which was now subject to the Danish chancellery in Copenhagen. In this sense, Norway was treated like a Danish province, but it otherwise kept its own laws and traditions. The local administration followed the same basic model as Denmark, but there were far fewer len in Norway, so the number of noble royal stewards was limited. Instead, the administration was managed by an intermediate group of bailiffs, who were recruited locally from burgher and wealthy peasant families.

The duchies, in contrast, had their own separate nobility, the so-called Knighthood. The Knighthood was also represented by a council (albeit with significantly less influence than the council of the realm), but, in practice, this council ceased to function after 1544. However, the entire nobility and the town mayors were regularly called to meetings of the estates (stændermøder), where issues such as new taxes and legislation were discussed.

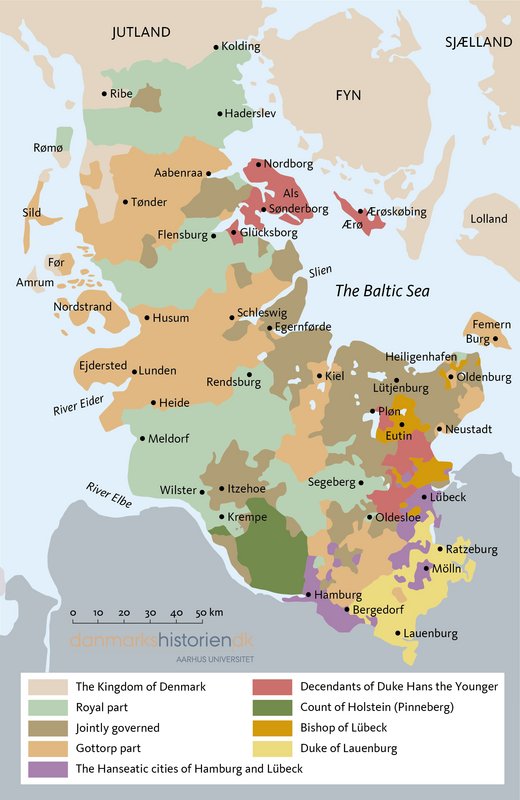

In 1544, during the reign of Christian III, the rule of the duchies was divided between the king and his brothers Hans ‘the Elder’ and Adolf. Henceforth, they each ruled a number of districts, where they appointed the local governors (amtmand) and from which they received income. In addition, the so-called ‘joint government’ (fællesregering), consisting of the three dukes and the nobility, was responsible for matters relating to the nobility and their land, as well as other important topics.

Hans the Elder died without heirs in 1580. From this point onwards, power in the duchies was mainly divided between the two ducal lineages: the royal dukes and the Gottorps, who were descended from the aforementioned Duke Adolf. Another duke had entered the picture when, in 1564, Frederik II’s younger brother, Hans ‘the Younger’, received a small part of the duchies. The estates did not acknowledge him, however, so he was not given a share in the joint government and as a result could only exercise power on the local level.

Map showing the internal borders in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein in 1622. From 1490 onwards, the duchies became a political patchwork as a result of divisions between the kings and other ducal lines. The divisions were dynamic, so the map changed several times, but, from 1582, it was mainly divided into a royal part, a Gottorp part, a jointly governed part (consisting of noble manors) and Hans the Younger’s areas. In 1622, these latter areas were divided into five very small principalities. The next major change occurred when the Danish king gained control of the Gottorp part of Schleswig in 1720 and of Holstein in 1773, which meant that the joint government could also be dissolved. © danmarkshistorien.dk

State income and expenses

The Reformation had given an important boost to the Danish state. Aside from this, the demands of war were the main driving force behind the development of Early Modern European states. Not without reason have these states been described as war machines. In Denmark, this development only became noticeable in the seventeenth century. Between 1536 and 1611, the country was involved in only one war, and in peacetime the king had only the navy and some castles and fortresses.

The king did not dispose of a regular army, however. The Danish nobility were obliged to provide 1,200 cavalrymen when required, and the Schleswig-Holstein nobility six hundred. The towns were also able to provide a certain amount of armed men, and during the Seven Years’ War peasants were drafted into the army. War was mainly conducted with mercenary soldiers. It was expensive, and extra taxes were levied on the population in wartime. During the Seven Years’ War, it was difficult to raise enough funds. The war left the country with a debt that had to be paid, but once this was achieved the taxes could once again be scrapped.

It was possible to pay off the debt because the king had a large income. This came from two major sources: the Sound toll and the Crown land, as the Reformation had left the king as owner of half the country’s land. These sources of income were enough to fund the court and the navy, which were the two most important expenses in peacetime. The Church was financed locally by the tithe and parsonage land, and the judiciary was paid for by those who used it. Unlike most other European rulers, the Danish king therefore had his finances under control.

The military and fiscal state

The king’s strong financial position was challenged once wars became more frequent and the threat of war more constant. After the Kalmar War, Christian IV began to build up a peacetime army, which grew larger in the years that followed. It consisted partly of conscripts – peasants and farm servants, who were given training and could muster when required – and partly of professional soldiers – full-time, salaried mercenaries. The king preferred professional soldiers, who were more effective, but the council of the realm and the nobility preferred conscripted soldiers, who were far cheaper. In practice, therefore, there was a mixture. In 1643, there were 16,000 conscripts in Denmark and almost half this number in Norway, and 11,000 salaried soldiers, who were concentrated in the duchies. This was many more than previously, but it was still not enough to stand up to the Swedes, whose army had grown to a far greater extent.

The army cost money. After the Emperor’s War, taxes were no longer levied occasionally when required, but instead collected annually. The peasants had to pay but the council of the realm had to agree to taxes being levied. The councillors were not enthusiastic about increased taxes, since they reduced the peasants’ ability to pay rent to their noble landowners. The council of the realm managed to make some of their peasants exempt from taxation, but they also had to agree to several rounds of tax increases. Denmark was on the way to becoming a military--fiscal state.

Power struggles between the king and nobility

The battle for a larger army and increased tax revenue gradually became a more general struggle for the development of the state. In 1638, Christian IV decided to summon all adult noblemen and representatives of the towns and clergy to a meeting of the estates, in the hope that the estates would be more compliant than the council of the realm. The meeting agreed to new taxes, but the money had to be managed by a new group of noble commissioners (landkommissærer). During the meeting, the burgher estate challenged the nobility’s tax freedom and income from the len, as they believed these represented good potential sources of income. Nothing really came of this challenge, but the old order had been questioned.

After the Torstensson Feud, the country was once again in need of money, and the king’s prestige had also diminished. The meetings of the estates and the commissioners gained more influence over matters such as the appointment of new councillors of the realm. At the same time, both the burghers and the so-called ‘ordinary’ nobility were critical of the king’s re-armament and the taxes it required. Tensions also arose after Christian IV appointed some of his sons-in-law to powerful positions, including Corfitz Ulfeldt, who was married to the king’s favourite daughter, Leonora Christine.

A decisive test of strength occurred after the death of Christian IV in 1648. The situation was uncertain because there was no elected successor to the throne. At a meeting of the estates, the individual estates raised their usual demands, but the representatives of the nobility also requested that the estate meetings take over much of the council of the realm’s power in connection with tax and legislation. Had this request been granted, it could have steered political developments in the direction of a permanent parliament with real influence, like that in England. However, the council of the realm instead decided to prioritise its own standing. Frederik III’s coronation charter increased the council’s control and, among other things, established rules for how its members should be appointed. In the years after 1648, the council of the realm attempted to re-organise the country’s defence in a way that better suited its ideas. The main emphasis was on conscripted troops, and it sought to increase control of the army.

The royal coup in 1660

Denmark survived the end of the Second Northern War in the summer of 1660, but otherwise the situation looked extremely bleak. Large provinces had been lost, and much of the rest of the country was severely impoverished. In addition, the country was heavily in debt, and there was a lack of money to fund the military contingent that was deemed necessary. A meeting of the estates was convened in Copenhagen in the autumn in order to discuss the situation. The meeting soon gave rise to disagreements about how the necessary money should be raised. The nobility favoured a tax, which would affect traders, while the burghers and clergy wished to reduce the nobility’s tax freedom and benefits from the len. The only matter on which the estates could agree was military cutbacks.

During the meeting, discussions began to centre on the constitution. The burghers demanded more power for the meetings of the estates (stændermøder), just as the nobility had done twelve years previously. Once again, this demand was rejected by the council of the realm. The burghers and the clergy then joined political forces and suggested that the monarchy become hereditary. This would remove an important basis for the power of the council, since it would no longer be able to impose conditions via the coronation charter when a new king was elected. The nobility then gave in on the tax issues, but this offer came too late to satisfy their political opponents.

From this point on, the situation developed into a kind of military coup, which was possible because the army that was formed after 1658 consisted of mercenary soldiers controlled by the king and predominantly foreign officers. On 10 October, Frederik III put Copenhagen into a state of emergency and effectively imprisoned the nobility inside the town. Three days later, the nobility surrendered, and on 17 October the coronation charter was abolished. It was decided that a committee should write a new constitution, but in the end the task was left to the king. In December, he dissolved the meeting of the estates and assumed complete control. Absolute monarchy had been established and would last for approximately two hundred years.