2. Living conditions and society

Denmark experienced demographic and economic growth throughout most of the period. Society was still made up of estates, just as it had been in the Late Middle Ages, but the Church’s role was weakened and the nobility’s role strengthened. Agriculture was by far the most important sector, with more than 80% of people living in the countryside, and most of the towns depended upon their hinterland. During this period, however, Copenhagen began to grow faster than other towns and gradually developed a community of burghers to rival the nobility.

Climate and disease

Nature was a decisive factor in human life. People were able to understand and work with natural forces sufficiently to ensure that the peasant population could produce enough food for themselves and a surplus, but the balance was always fragile, and basic conditions became somewhat worse during the period. The general decline in average temperatures, which had begun in the Late Middle Ages, continued and resulted in poorer conditions for agriculture. Cold springs and wet summers and autumns could lead to the failure of the harvest, which increased the price of grain and meant that poorer people found it difficult to buy enough food.

The population was also subject to changing natural conditions in other ways. There was no effective cure for common infectious diseases or other illnesses, and every year disease killed off some of the weakest members of society. Around a third of children died before the age of five, but chances of survival improved beyond early childhood. Although it was not uncommon to live beyond the age of 60, epidemics could still take people in their strongest years.

Population growth in the sixteenth century

Despite the challenges of climate, bad harvests and disease, most years between 1536 and 1660 saw more children born than people carried to the cemetery. The population of the kingdom grew significantly. Precise data is lacking, but a rough estimate is that the number of families or households in the countryside increased from around 75,000 at the beginning of the period to 100,000–120,000 in 1640. This estimate includes Skåne, Halland and Blekinge but not Schleswig. The urban population also grew. It is difficult to provide exact figures for the total population, but it would be safe to assume that the population increased from 500,000–600,000 at the beginning of the period to around 800,000 in 1640. Compared with southern and western Europe, however, Denmark was still sparsely populated.

Population growth in Denmark ended in the final decade of the period, when severe epidemics devastated several parts of the country one after the other. The worst of the epidemics hit the southern part of Jutland and Schleswig in 1659 and killed over half the population in the most affected areas. Alongside these epidemics, there was also war. Population growth in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries coincided with a period of relative peace, but when this peace gave way to war, there were consequences for everyone.

The society of estates after the Reformation

Denmark continued to be a society of estates (standssamfund), with different rules and conditions for each estate. The nobility was now undoubtedly the country’s most important estate. More closed than ever before, the nobility was limited to those who were born into it.

Before the Reformation, the nobility had shared its elevated status with the clerical estate. After the Reformation, the clergy was still an estate in its own right with specific privileges, but it now had more in common with the burghers than with the nobility. The burghers and the clergy both had privileges but were not granted any significant share in the political leadership of society. Access to the two estates was gained by obtaining an ecclesiastical position or by acquiring burgher status as a merchant or a craftsman. While it was common for a son to follow in his father’s footsteps as a pastor, merchant or craftsman, it was by no means guaranteed. Both estates were built on qualification. Workers and servants in towns were townspeople but not burghers.

The fourth estate was the peasantry. In principle, the peasantry included all those who lived in the countryside who were not pastors or members of the nobility – in other words, everyone from farmers with access to land to cottars and servants. The vast majority of children born into the peasant estate remained peasants, but there was a certain amount of exchange with the burgher estate and the clergy, so that some peasant children advanced while a few children of pastors and burghers joined the peasantry. One of the most famous Danish reformers, Hans Tausen, who eventually became a bishop, was the son of peasants. Outside the four estates were groups such as nomadic beggars and Romani populations, who were not considered full members of society.

Peasant society

Approximately 80% of the population lived in the countryside and belonged to the peasant estate in the broadest sense. With certain exceptions, this was the case across the whole of Europe: only in places like the Netherlands and northern Italy did the urban population account for a significantly larger proportion of society. In Denmark, technology did not advance significantly during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There was little progress in the way of new tools, crops or cultivation methods.

The basic unit in the countryside was the farm. Danish farms varied in size, but most of them were large enough to support a family while being small enough for the family to provide most of the necessary labour to run the farm.

Farm, family and household

Marriage usually went together with taking over a farm. This was because Denmark, like other areas in northern Europe, was dominated by the nuclear family model, where the family was built around a married couple and marriage meant the founding of a new family. Couples married only when there was a farm to take over, and this was often relatively late. Sporadic data from the seventeenth century suggest that most people got married for the first time around the age of 30. If the husband became a widower, he usually remarried. A widowed wife often remarried too, as long as she was still young enough to have children. If not, she handed over the farm.

Husband and wife had a number of sharply divided work tasks, none of which could be dispensed with. It was the man’s job to plough with horses, to sow crops and to harvest them with a scythe, while the woman’s tasks included looking after the cows, making butter and beer and baking bread. A man and a woman on their own were seldom able to run a farm without extra hands. Children helped from an early age; if a couple did not have adolescent or adult children at home, they supplemented the labour force with male and female farm servants. The family and the servants constituted the household, which worked and lived together. This formed the basic unit of society in contemporary legislation and religious prescriptions alike.

Servants and cottars

The vast majority of servants were young and unmarried, and the time they spent in service was viewed as a kind of training. The idea was that, after a number of years, they would themselves be able to take over a farm. At the beginning of the period, there were almost enough farms for everyone, but this ceased to be the case as the population grew. The rural society reacted in one of two ways: by dividing the existing farms into two, or by building new houses without accompanying land. For various reasons, the first method was more widespread in Jutland and Schleswig, and the second on the islands and in Skåne, where there emerged a large group of landless cottars (husmand; plural husmænd) as a consequence. Even though population growth itself is a sign of a surplus in society, it conversely led to an increasing number of people living in poor social conditions.

Villages and farms

In most of Denmark, farms and houses were located together in villages. It was only in certain parts of the provinces east of the Øresund, including Bornholm, and in large parts of western Jutland that the farms were more scattered. The villages in the rest of the country varied consider-ably in size, from just a handful to over fifty farms and houses, though the average village consisted of between ten and twenty farms and houses. This corresponded to a community of between fifty and one hundred and fifty people, who lived closely alongside one another but typically a few kilometres from neighbouring villages. Each individual farm was an independent economic unit, but people were very dependent on their neighbours. Cultivated land consisted of large fields, each one of which was divided into several hundred long and narrow strips, or ‘selions’, called agre. Every farm had its own strips spread across the village fields, meaning that all the inhabitants had a share of the different types of land the village had at its disposal.

Co-ordination and common grazing

Every peasant and his household ploughed, sowed, fertilised and harvested their own strips. It was essential, however, that everyone cultivated the same crop in the same part of the field in a given year, and that everyone worked at the same time. Only part of the land was ploughed and cultivated every year. The rest was left to produce wild grasses and herbs, and it was here that the village’s animals were grazed together. In most of the country, common fencing separated the pastures from the arable land.

This meant it was important to co-ordinate work in the village; peasants thus attended bystævner (village gatherings), where joint decisions were made. Only peasants with the use of a farm and associated land (gårdmand; plural gårdmænd) had the right to vote at these gatherings, but everyone had to follow the rules they imposed. These rules also began to be written down during the period, and are known as ‘village bylaws’ (vider or vedtægter).

The whole system has been described as a collectively regulated system of cultivation, not because the cultivation of the fields itself was collective but referring instead to a system in which cultivation was co-ordinated and grazing was common. Nor was the system characterised by solidarity. Some farms had wider strips and thus more land on which to cultivate grain than their neighbours, and these farms also had the right to graze more animals on the village’s pastures and fallows. All this became increasingly important; as the population grew, more people came to use the same area, and the pressure on natural resources increased.

Social frameworks and meeting places

The collectively regulated open-field system of cultivation, dyrkningsfællesskab, was thus both a close physical neighbourhood and a way of co-ordinating work and the rights of people to the natural resources on which they depended. Since people lived so closely alongside each other and resources were scarce, conflicts often arose. Insults, fights and protracted disputes were common, and it was important for individuals to assert what they saw as their rights and honour – both to maintain their status and to retain their share of natural resources. Villagers were fined for actions that damaged the community. This could include failing to maintain a fence adequately so that animals were able to enter the grain field and eat the crop that the villagers’ lives depended upon. Many of the fines were paid in beer, which was drunk at village festivals during which the positive side of close community life was cultivated. The community also united for weddings, funerals and religious festivals.

Although people lived most of their daily life within the village, the world was by no means closed to them. At church, people met those from other villages in the parish. They had connections to manors and towns, and they gathered at the local courts or assemblies (herredsting). Marriages were often between people from different villages.

Subsistence and the market economy

The production of grain, especially rye and barley, was by far the most labour-intensive and crucial part of farming, since grain provided the basic elements of the diet, such as bread, porridge and beer. Horses, cattle, sheep, pigs and poultry were reared. Horses were used as draft animals, while cattle, sheep and pigs ensured the villagers had meat, milk, butter and wool.

Most of what was produced was used by the villagers themselves. To meet household needs it was necessary to produce a range of different crops and animals, even in places where natural conditions were less than ideal. The peasant population was not only occupied with farming the land and raising livestock; peasants also spun yarn and wove cloth, and produced tools and repaired buildings. The right to fish in rivers and lakes was usually reserved for the king or the nobility, but coastal fishing was permitted, and, even in the sixteenth century, peasants travelled long distances to fish in coastal waters.

Farms produced not only enough for their own subsistence but also a surplus to cover duties to the Church, the landowner and the king, as well as to have something to sell. Grain was by far the largest part of production and it was also an important tradeable commodity, especially from regions with fertile soil. The other main tradeable commodity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was the steer (a castrated bullock raised for beef). Steers were produced across the country but particularly in the western regions. Increasingly, the nobility monopolized the most profitable parts of this production.

Danish farmers generally had something to sell during the period. Production kept pace with the growing population, and increasing quantities of goods were exported, stimulated by rising prices for agricultural commodities until 1630–1640. The market economy was on the rise.

Wealthy peasants

A number of peasants became traders and sources of credit, lending money to their neighbours, and, in some areas, charging interest. Peder Hansen and Karen Jakobsdatter from Solrød, southwest of Copenhagen, had a fortune of no less than 3,000 rigsdaler upon their deaths in 1643. They had lent out 1,000 of these rigsdaler against promissory notes, and belonged to the very top of the peasant estate.

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, gårdmænd generally enjoyed good conditions. They took advantage of the opportunities to sell cattle, grain and other products, and they benefitted from a period of peace and low tax burdens. They spent some of the money they earned on goods that the peasant community did not produce, including clothes, cooking utensils made of copper, brass or tin, spices, beer and spirits. Some of the wealthier households owned silver cups, spoons, buttons and buckles. In Peder and Karen’s home in Solrød, there were two silver pitchers, six silver cups and twenty silver spoons.

The landless and the poor

By no means was everyone as lucky as Peder and Karen. Some farmers (gårdmænd) experienced difficulties, but it was the growing class of cottars (husmænd) who had a particularly challenging existence. Cottars had very little or no land and therefore no grain or steers to sell. They often had the right to graze a few animals on village commons, but they could not grow their own grain, making rising grain prices a problem for them. Some cottars specialised in different crafts, but typically only blacksmiths had a stable and secure business. Other cottars lived as day labourers, doing odd jobs for payment, often in the form of food.

Some found it difficult to earn enough to live, particularly those who were physically debilitated. The so-called ‘deserving poor’ were, in principle, entitled to help from the rest of the parish. The Church collected alms for the poor and some buildings were turned into poorhouses or asylums. Paupers without local connections were excluded, however, and some ended up as vagabonds. It is estimated that over 5% of the population in the mid-seventeenth century belonged to a group of poor people without proper employment or a secure livelihood.

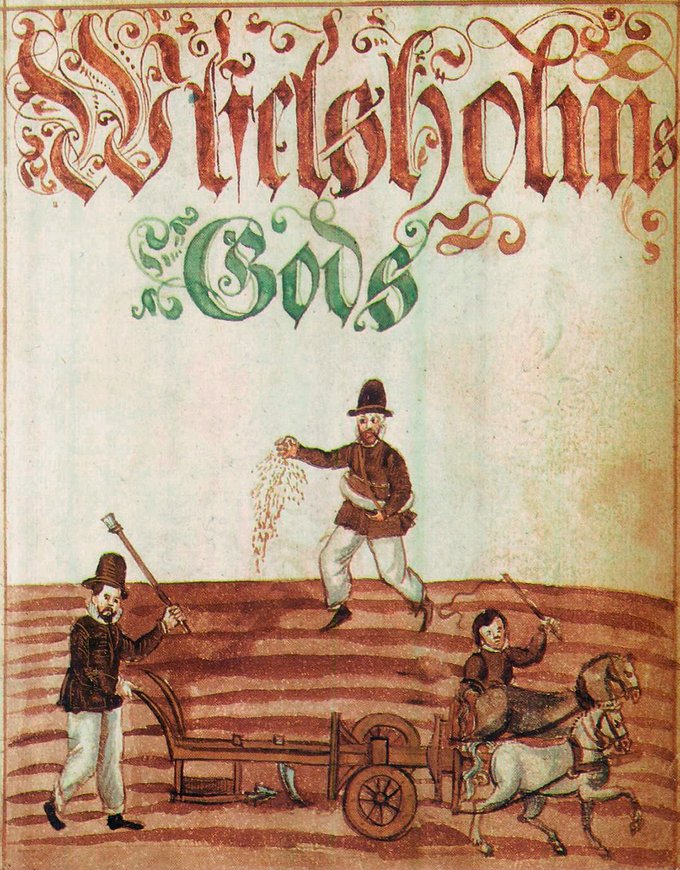

Peasants carrying out two of the most important agricultural tasks: ploughing and sowing. Ploughing was heavy work that usually required four horses for the plough and two men. Sowing the precious grain was a highly entrusted job that the peasant farmer usually performed himself. This picture is from the front page of an urbarium, a list of properties, that nobleman Jacob Ulfeldt (died 1593) had made in 1584. The urbarium is a part of the collection of the National Museum of Denmark. Photo: National Museum of Denmark

The tenancy system

Only a few Danish peasants owned their own farm. The vast majority, with the exception of most of those on Bornholm and in Schleswig, were tenant farmers (fæstebønder; singular fæstebonde). The tenant relationship meant more than simply renting the land and farm – a tenant farmer was the subject of a noble landowner, to whom he owed not only work and duties but also fidelity and obedience.

The Danish term fæstebonde comes from the word fæste, which means ‘to enter into a fixed agreement’. After the Reformation, it was part of Danish law that tenure was for life. Farms were not formally inherited, but, in practice, it was quite common for them to be passed down the generations, though such an inheritance had to be negotiated and paid for.

The peasant had to pay an annual fixed fee to the landowner for the right to use the farm, the landgilde (land rent). This usually consisted of a portion of the farm’s produce, particularly grain. The land rent remained more or less stable throughout the period. It was relatively moderate compared with what it had been around 1300, but the combined tax and rent burden rose throughout the seventeenth century, particularly after 1660.

As well as paying fixed and variable duties, tenant farmers were also obliged to perform hoveri (corvée) for the noble landowner. This was of limited significance until the mid-sixteenth century, however, since most of the demesnes (herregårde) farmed directly by the nobles were small. Most landowners had their peasants spread over vast areas of land, so it was difficult to get them to perform hoveri at the demesnes.

Land ownership and use

After the Reformation, the king was direct lord over approximately half of the country’s peasants; the majority of the rest were subjects of noble landlords. In many villages, the peasants of different landowners lived alongside each other. From the second half of the sixteenth century, the king and the nobility began to exchange farms with each other on a large scale, and the nobility also exchanged, bought and sold land among themselves. The king sought to gather his land holdings in certain areas around important castles, motivated by the desire to hunt and to rule over entire areas.

The nobility, in contrast, became large-scale farmers. They wished to take advantage of favourable prices by producing grain and steers in large quantities. Noble landowners made their own demesnes larger by appropriating land from peasant farms. Labour on the demesne fields was carried out as hoveri, so the landowners wanted to own as many peasant farms close to the demesne as possible. The king and the country’s highest court gave the noble landowners free rein to appropriate peasant farms and increase unpaid labour.

In the middle of the seventeenth century, around half of the nobility’s tenant peasants were ugedagsmænd (‘weekday men’), who had to provide at least one day’s unpaid labour a week. This was a big change, though not as dramatic as that which occurred in eastern Germany and Poland, where demesnes and hoveri increased even more and the peasants were subjected to a lifelong type of serfdom (livegenskab). Even within Denmark, the development differed; the king’s tenant farmers, for example, were significantly less affected by hoveri than others.

In Schleswig, the majority of peasants were direct subjects of the king or dukes, as tenants of the Crown or freeholders. Most of these peasants were completely free of hoveri from the 1630s, and, in this region, farms were hereditary. Peasants in northern Schleswig generally had a freer position and a better financial situation than those in the kingdom of Denmark, but the opposite was the case for peasants working on noble farms in southern Schleswig and southeast Holstein, where a type of serfdom was introduced.

The nobility

In the period explored in this module, approximately two to three people in every thousand were members of the nobility, which amounts to a couple of thousand people in total. The nobility was a very closed estate. Only children of marriages between two members of the nobility became members themselves; the only other additions to the estate came through the steady immigration of foreign noblemen.

The economic basis of the nobility was land, and, overall, the Danish nobility was wealthy. Around five hundred noblemen and noble widows held somewhere in the region of eight hundred demesnes and 30,000 peasant farms. There were, however, significant differences between individual members of the nobility. In 1625, the country’s wealthiest nobleman, Eske Brock, owned eight demesnes and around a thousand peasant farms, while the least wealthy noblemen could own as few as ten peasant farms. These differences were overall smaller than those in other countries, not least neighbouring countries such as Poland and Sweden, where the nobility was split between a small group who were very wealthy and a large group who were poorer. In contrast to this, the majority of Danish noblemen were relatively well off.

The wealth of individual people or families changed continually as inheritance was divided between siblings. This led to fragmentation, but, on the other hand, it meant that land could be re-combined with every marriage within the relatively small community of nobles. This all created a great deal of dynamism in land ownership, which intensified at the end of the period when a strong market for land developed. In general, however, the wealthiest noblemen were themselves the sons of rich men, while the fathers of the poorest had rarely owned much, and a poor nobleman had limited chances of marrying into money.

The Nobility and the Society of Estates

In this film, Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen discusses the society of estates, the development of the nobility, and the relationships between the different estates. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The nobility as the first estate

The social role of the nobility was to be landowners, warriors and administrators. Most members of the nobility were active in farming during this period, taking advantage of favourable times. Although the Danish nobility tried to hold on to their role as warriors, this status gradually declined. On the other hand, their role as administrators on behalf of the king became increasingly important. The nobility retained the monopoly on a number of positions in the country’s central government as well as in the local and regional administration, primarily the powerful and lucrative offices of councillor of the realm and steward of districts and royal manors (lensmand).

After the Reformation the nobility replaced the Church as the first estate of the realm and played a leading cultural role. Top members of the clergy moved down the hierarchy whilst the nobility received a tremendous cultural boost. Before the Reformation, university education had been designed to prepare people for an ecclesiastical career and was reserved for noblemen or others who wished to pursue this path. From the mid-sixteenth century onwards, however, members of the nobility prepared for careers in the king’s service by undertaking educational journeys in Europe, often lasting several years. They studied at universities (without taking exams), resided at courts and knightly academies and came home with a higher level of literacy and linguistic competence than before – as well as a completely different view of the world.

New noble manor houses sprang up in the landscape. The earliest still resembled fortified castles, since the peasant uprisings during the Count’s Feud were not easily forgotten by the nobility. But soon the design of these manor houses came to be guided by the desire to demonstrate power and splendour according to the latest fashion. Hesselager Manor on Fyn was built in the 1540s by councillor of the realm and chancellor Johan Friis (1494–1570). It combines defence elements with gables in the Italian Renaissance style. Photo: hesselagergaard.dk

Together with the king, the nobility now set the trends in architecture and art. Manor houses became larger and more magnificent than before – not only the main buildings but also the large barns and stables. The nobility dressed in a far more distinguished way than the rest of the population, and they had the exclusive right to wear certain items, such as gold chains. They had their portraits painted and, on their deaths, their power was manifested in printed funeral sermons with long biographies and large tombstones in churches. Many noblemen also marked themselves out as good Lutherans by donating money to the poor and to schools. All of this was based on the enhanced political role, economic progress and increased level of education of the nobility, and the changes of the Reformation.

Schleswig and Holstein had their own nobility, the Schleswig-Holstein Knighthood (Ritterschaft). This group went even further than the Danish nobility with regard to large-scale agriculture, and experienced much of the same progress and educational development.

Towns of different sizes

There was a sharp formal distinction between the town and the countryside in Denmark. Privileged towns were subject to completely different rules from the countryside, and they were governed by their own mayor and council. Towns lived by selling the surplus produce from the surrounding countryside and by supplying the hinterland with imported goods and the products of more sophisticated craftsmanship – and they had the monopoly on both. A minimal amount of trade and some basic crafts (blacksmiths, wheelwrights, cobblers) were tolerated among the peasants, but only in Schleswig and on some small islands could peasants trade on a larger scale. For a long time, it was the nobility that posed the greatest competition for the towns, since many noblemen exported their own grain and steers, but this practice declined towards the end of the period. Towns also engaged in agriculture themselves in order to cover some of their own needs.

Denmark had relatively many towns, but most of them were small, with under a thousand inhabitants, and had little significance for the general economy. However, the larger urban centres such as Aalborg, Aarhus, Ribe, Odense, Helsingør and Malmö – with populations of around 3,000–6,000 – flourished. This also applied to towns such as Haderslev, Tønder and Flensburg in Schleswig.

Merchants and craftsmen

The trendsetting class in the towns in this period were wealthy merchants, who built solid houses of two or even three storeys, with space for dwellings, shops and warehouses. The wealthy merchants in the provincial towns engaged in the export of Danish food products and the import of consumer goods. Among the more important customers were the noble landowners in the area, but peasants also contributed to turnover. Some of the wealthiest merchants had their own ships, many of which remained in local waters, though some sailed around Skagen and on to the Netherlands.

Merchants were at the apex of the urban hierarchy, while the craftsmen constituted its base. Some of them sold to the town’s burghers; others earmarked their products for the nobility, pastors and peasants in the countryside. Again, the larger towns in particular had craftsmen capable of satisfying a discerning noble clientele. However, even in the larger towns, craftsmen did not produce goods for more distant markets. Danish craftsmen worked for customers in their own town and its hinterland, and in some cases for a broader region, but their market did not extend beyond this. Most craft production was still regulated by guilds, which varied in number according to the town’s size.

The burghers included merchants and craftsmen. Widows could gain permission to run a workshop or business and thus become burghers themselves, but women, children, servants and day labourers were otherwise only townspeople – not burghers. Journeymen and apprentices were in principle employed in the same way as servants in the countryside and belonged to their master’s household. The towns included households whose heads were not burghers but married journeymen or day labourers. In addition, there was a small group of clergymen (pastors, bell ringers and schoolteachers), as well as a significant number of poor people. These included the town’s ‘own’ poor, who received alms from the Church or perhaps through a small ‘hospital’, and the non-local and thus unwanted poor.

Growth of the capital

At the end of the Middle Ages, Copenhagen was already Denmark’s largest urban settlement, closely followed by Malmö and Flensburg. Between 1536 and 1660, Copenhagen began to grow much faster than other towns and by 1660, it was as big as all the Danish provincial towns combined. The first relatively reliable population figure is from 1672, showing that 42,000 people – or nearly ten times the population of the kingdom’s largest provincial towns – lived in Copenhagen. It has been estimated that around 10,000 people lived in Copenhagen during the Reformation period, which means that by 1660, the city’s population had more or less quadrupled.

One of the reasons for this was that the city had effectively been made the capital, as it was home to two of the country’s central institutions: the royal court and the navy. These two institutions were by far the country’s largest employers and customers. They brought many people to the city, and created a huge turnover for its traders – from wealthy merchants to craftsmen, innkeepers and prostitutes.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, Copenhagen boasted a burgher estate, the most affluent members of which could match the wealth of the nobility and was unrivalled in the provincial towns. Christian IV gave the city a new boost when, in the spirit of the time, he tried to promote economic growth by establishing trading companies and large, organised workshops (manufakturer) intended to promote Danish trade and craftsmanship through economies of scale and privileges. This policy, which historians have subsequently referred to as ‘mercantilism’, was concentrated in Copenhagen, though it had few lasting results aside from the establishment of a trading post in Tharangambadi (known as Tranquebar) in India.

Craftsmen also had good opportunities in Copenhagen because the city’s size and growth led to increased demand for particular services and products. Socially, there were greater internal differences in Copenhagen than in other urban settlements, since some masters had large workshops with several journeymen and apprentices. The city was also home to a large group of servants as well as a poor underclass, who survived by doing casual work or begging.

Copenhagen was an international city that attracted people from the king’s many territories and countries but also from northern Germany and, to a lesser extent, other parts of Europe. German was spoken widely in Copenhagen, where the German-speaking community had their own church, St Peter’s.