3. Denmark and the rest of the world

Throughout the entire period, the Danish kingdom was a part of a larger state formation. The Kalmar Union was over, but the Danish king remained king of Norway and duke of Schleswig and Holstein. He also ruled over the dependencies (bilande) Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Gotland. Historians like to use the term ‘conglomerate state’ to describe these different countries and territories under the same king but with different local systems. The conglomerate state meant that the king had interests from the North Cape to northern Germany, and from the Atlantic to the Baltic Sea.

Lutheran Europe and north German neighbours

Close ties between countries in northern Europe were nothing new, but the Reformation made them closer by establishing a common confessional community in the region. The Lutheran Church became the state Church in the Nordic countries and in most northern and eastern German states, and it came to separate the region from the Catholic south. Culture and ideas flowed into Denmark from the rest of Protestant Europe. The Danish clergy studied in the Lutheran areas; young journeymen travelled there to seek work, and it was also from these areas that many immigrants came to Denmark.

Denmark was therefore closely connected to northern Germany. Holstein was a north German duchy, and there was also strong German influence in Schleswig. German was one of the two languages of the central administration – and Low German gradually gave way to High German as a language for writing and culture. The four queens of the period were German, as were most sons-in-law of the royal family, so German was an everyday language for the kings and much of the court.

Although the German language shaped cultural relations between Denmark and its southern neighbours, in political matters the Danish kingdom was the dominant force. The Lutheran areas of northern and eastern Germany were divided into many principalities, duchies and counties, all of which were significantly smaller than the Danish kingdom, so the king of Denmark usually had no reason to fear his German neighbours. This was also the case for the once-powerful Hanseatic League, which was declining in influence.

The Netherlands as an important trading partner

From an economic perspective, the Hanseatic towns began to lose significance for Denmark as the Netherlands started to emerge as a strong trading partner. The Netherlands was home to northern Europe’s highest concentration of large urban settlements, with a much larger merchant fleet than their north German competitors. In the first two thirds of the sixteenth century, the Netherlands belonged to the House of Habsburg, but the northern provinces became an independent federal republic following an uprising in 1568.

Over the course of the sixteenth century, the Netherlands became the most important trading partner for the entire monarchy. It bought grain and steers from Denmark and the duchies, as well as fish and timber from Norway, and exported processed and exotic goods in return. In addition, the Dutch hunted whales in the North Atlantic, in waters that the Danish kings claimed sovereignty over. The Netherlands also contributed significantly to the king’s revenue through the Sound toll, since they were engaged in a large part of the extensive trade between the Baltic region and northwestern Europe. The Dutch Republic became a major military power over the course of the seventeenth century, which further increased its opportunities to exert influence on Denmark. It was also culturally influential. Most of the painters who portrayed the Danish kings and the master builders who designed their palaces were from the Netherlands.

Foreign policy in the Reformation period

1523 marked not only the end of Christian II’s reign but also, in practice, the end of the Kalmar Union. In this year, Denmark and Sweden gained their own kings, who both came to power as a result of an uprising against Christian II. Frederik I’s major task was to consolidate his royal power. He was unable to secure the succession, so his death in 1533 left a void that led to a civil war, and it was only in 1536 that Christian III ruled over the whole of Denmark. After this, Christian III’s major project was to implement the Reformation.

Following the fall of Christian II, the most significant external threat came from the Habsburgs, his influential family by marriage, and especially from his brother-in-law, Emperor Charles V, who was head of the Holy Roman empire, ruler of the Netherlands and defender of the Roman Catholic Church. Fortunately, Charles V had other concerns. In 1531, he gave Christian II resources to launch an attempt at reconquest, but these means were limited, and he stopped funding the deposed king the following year. The threat posed by the emperor was not completely extinguished, however, until he and Christian III entered into a peace treaty in 1544.

The Danish kings had tacitly left Sweden to Gustav Vasa, who, in the meantime, had implemented the Reformation and created a more centralised monarchy with the consent of Christian III, who had even helped to suppress a Swedish peasant uprising.

From the Seven Years’ War to the Kalmar War

When Frederik II and Erik XIV came to the thrones of Denmark and Sweden respectively in 1559 and 1560, they each inherited a strengthened monarchy. A mutual rivalry soon developed over supremacy in the Nordic and Baltic regions. This matured into a period of recurrent wars that would last approximately two hundred years.

At first, the two Nordic states competed and fought without much interference from others. The first major war, known as the Nordic Seven Years’ War, took place between 1563 and 1570 and was fought mainly as battles over fortifications and raids into enemy territory. Swedish armies attacked Skåne, Halland, Blekinge and Norway, while Danish armies moved into the southern Swedish provinces and, on one occasion, so far into Sweden that they approached Stockholm. Both parties hoped that the areas they reached would change sides, but both were disappointed. It became a war of attrition that drained resources and undermined the will to fight in both countries. Denmark took control of the island of Øsel in Estonia, but otherwise gained nothing from the long and costly war.

For the next forty years, Denmark followed a cautious foreign policy and accepted continued Swedish expansion in the Baltic region. However, this position was challenged by Christian IV when he came to power in 1596, and he eventually pressured the council of the realm into declaring war with Sweden. What became known as the Kalmar War was fought between 1611 and 1613. It began with attacks on the Swedish fortresses Kalmar and Älvsborg, which the Danish army conquered, but then stalled. This time, however, there was greater mutual willingness to enter into a peace agreement. Denmark received a sum of money for the Swedish fortresses, and a long-standing dispute about the demarcation of the border between Norway and Sweden in the far north was settled in favour of Norway.

Denmark, Sweden and the Thirty Years’ War

Danish foreign policy had long focused on the north, and Danish kings had felt safe in the knowledge that northern Germany was a thoroughly divided area. This was undermined by the start of the Thirty Years’ War in the German and central European region. In the early 1620s, the imperial and Catholic party won important victories and took several hitherto Protestant areas. This troubled both the German Protestant states and the other major powers that rivalled the Holy Roman emperor.

England, the Netherlands and France urged the Danish and Swedish kings to intervene. Christian IV was willing. If he could establish himself as leader and protector of the German Protestants, it would strengthen his position, and he feared that Sweden would pick up the baton if he failed to act. The council of the realm was against the idea and blocked Christian IV from acting as king of Denmark. It was therefore as the duke of Holstein that Christian re-armed and became more active in north German politics. In the long term, this led to a war, which Christian lost as he was confronted with both the emperor and an association of other German Catholic states called the Catholic League. In 1626, the Catholic League defeated the king at Lutter am Barenberg, and, the following year, the emperor’s army under General Wallenstein occupied the duchies and the whole of Jutland, though the Danish King remained in control of the sea.

Peace negotiations were initiated, but they stalled. In February 1629, Christian IV met his Swedish counterpart Gustav Adolf in Ulvsbäck parsonage at the Danish–Swedish border. Gustav Adolf suggested the two countries join forces and continue the war under Swedish leadership. However, Christian IV did not wish to play second fiddle in a Swedish orchestra, so he declined. Instead, he used the negotiations with Sweden to put pressure on the emperor’s negotiators, so that he could receive tolerable conditions in the peace settlement at Lübeck in May 1629.

The peace marked the end of a section of the Thirty Years’ War from 1625 to 1629 known internationally as the Danish Phase; in Danish history it is called the Emperor’s War (Kejserkrigen).

The Torstensson Feud

While Denmark withdrew from the Thirty Years’ War, Sweden joined it; in the following years, the Swedish armies won major victories – from 1635, in alliance with France. This troubled the Danish king, who prepared the army and navy and also made diplomatic approaches to the emperor. In 1643, the Swedish army attacked the duchies without warning. The war between Sweden and Denmark became known as the Torstensson Feud after the commander of the Swedish army, Lennart Torstensson. The Danish defence collapsed, and the duchies and Jutland were occupied once again. The situation went from bad to worse when the united Swedish-Dutch fleet defeated the Danish navy at Fehmarn. Christian IV had aroused the wrath of the Netherlands because he had raised the Sound toll in order to finance his re-armament.

Denmark had to sign a humiliating peace treaty in Brømsebro. It ceded to Sweden the islands of Gotland and Øsel in the Baltic Sea, the sparsely populated Norwegian provinces of Jämtland and Härjedalen, and the Danish territory of Halland – though Halland only formally for thirty years.

Denmark and Sweden at war, 1657–1658

In 1648, the Thirty Years’ War finally ended. Sweden was one of the biggest victors and retained several areas in northern Germany. It also maintained a very large army. The new Danish king, Frederik III, wanted revenge but assumed that war would break out again between Sweden and Denmark sooner or later. Meanwhile, a treaty with the Netherlands settled the issue of the Sound toll and removed a possible threat from the Dutch. When the Swedes appeared to be entrenched in a war with Poland, Frederik III declared war with Sweden in 1657, thus starting what in Denmark has become known as the Karl Gustav Wars, after the Swedish king. King Karl Gustav (Charles X Gustavus) acted resolutely. He left Poland with his best troops and swept aside the Danish defences in the duchies and Jutland.

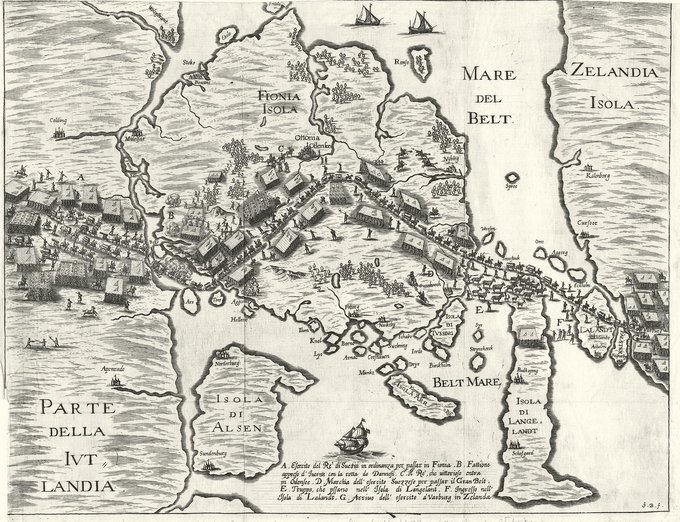

Swedish army raids across the frozen straits in January and February 1658 attracted international attention. Here they are depicted by an Italian artist on a copperplate engraving from 1670. The picture is more of a symbolic than a specific depiction, and the route is not entirely accurate. In reality, the army travelled from Jutland to Fyn over the frozen Little Belt a little further north, and crossed the Great Belt somewhat further south, than the map depicts – via Tåsinge and Langeland and on to Lolland. Photo: Royal Danish Library

Karl Gustav risked getting trapped in Jutland, as Denmark had allies who were gathering their troops to help. But a harsh winter meant that both the Little Belt (between Jutland and Fyn) and the Great Belt (between Fyn and Sjælland) froze over. The Swedish troops could thus cross the Little Belt and further over the Great Belt via Langeland and Lolland. This led to panic in Copenhagen. In the Peace of Roskilde on 26 February 1658, Denmark ceded Skåne, Halland (definitively), Blekinge and Bornholm, as well as the Norwegian districts of Bohus and Trondheim. At the same time, the king’s relative, the Duke of Gottorp, was declared ‘sovereign’ over his areas of Schleswig, which were slightly expanded. Since the Emperor’s War, the duke had had to follow the foreign policy advocated by Christian IV, even though he was against most of it, but now he changed sides and allied himself with Sweden.

Over the spring, Karl Gustav regretted that he had not taken the entire country. The Swedes still controlled Jutland, and a Swedish army moved ashore on the west coast of Sjælland. This time, however, Denmark did not surrender. Copenhagen was fortified and prepared itself for resistance. In February 1659, the Swedish army failed in its attempt to storm Copenhagen. At the same time, troops from Poland, Austria and Brandenburg moved into the duchies and Jutland, and the Netherlands sent a fleet to help. The Dutch were keen to avoid the same state having control of both sides of the entrance to the Baltic Sea. With this support, Denmark was able to build a new army, which defeated the Swedish army at Nyborg in November 1659. The inhabitants of Bornholm liberated themselves, and a Norwegian army recaptured Trondheim. At the peace negotiations in Copenhagen in 1660, the Danish king was allowed to keep these two areas, but the Roskilde peace treaty otherwise remained in force. The Danish conglomerate state still existed, but it was diminished and weakened.

The horrors of war

The wars of the period were felt by the civilian population. The Seven Years’ War in particular was waged with great brutality. Extensive destruction of the occupied areas was a dominant feature of warfare. The worst effects of this war were seen in the small town of Ronneby in Blekinge: when the town refused to surrender to the Swedish army, the Swedish king ordered his army to kill everyone – men, women and children.

In the wars that followed, systematic destruction and massive violence against civilians were reduced. Instead, the armies developed a system in which they promised not to murder, burn or plunder the occupied areas in return for regular supplies of money, food and other resources. The cost of such supplies was significantly higher than the taxes usually paid by the civilian population, and this system therefore represented a huge burden on the economy. The population in the duchies and Jutland felt this burden during the occupations of 1627–1629, 1644–1645 and 1657–1660, and the islands were also affected in the latter period.

The economic cost of war became increasingly difficult to bear. The country was able to recover from the first occupation relatively quickly, but the following occupation was worse and the wars of 1657–1660 put a particularly large strain on the economy. It was severely weakened in nearly all of the country – almost to economic collapse in northern Schleswig and southern Jutland, which were also hit by epidemics.

When foreign troops were in the country, many people buried their money and valuable objects, and several of these deposits have subsequently been found. Such finds testify to the fact that many people actually owned something of value, but they also show that many people never returned to dig up their treasures.

It made little difference whether the soldiers were allies or enemies. In 1659, it was even stated that the allies were worse. In relation to the war itself, the peasants were usually passive, but in 1659–1660 there were also bouts of guerrilla warfare in Sjælland, carried out by partisans: the so-called snaphaner. They were also called gønger because many of them came from the Gønge border region in Skåne, where people were more used to resisting.