4. Modernisation, internationalisation and urbanisation

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Denmark became a modern, class-divided society. Material growth was not distributed equally, and the different classes in the towns and cities experienced considerably different living conditions and ways of life. The boundaries between classes were fluid, however, and a degree of upward and downward social mobility was possible.

A significant feature of the period in Denmark was population growth, which in relative terms was one of the largest in Europe. The population grew from around 900,000 in 1800 to 2.7 million in 1910. One of the reasons for this was the declining infant mortality rate, which was linked to better sanitation, living conditions and nutrition. Infant mortality was highest among the most socially disadvantaged. There was also a high level of emigration; approximately 390,000 people left Denmark between the middle of the nineteenth century and the outbreak of the First World War. These emigrants were replaced by 81,000 Swedish immigrants who arrived between 1850 and 1910, mainly taking up work in agriculture, and by Polish immigrants, who helped to cultivate sugar beet. In 1914, 14,000 Polish women worked in the sugar beet fields on the islands of Lolland and Falster.

Urbanisation meant that large parts of the population moved from the countryside to settle in the towns and cities. In 1814, 20% of Denmark’s population lived in urban areas, but this figure had reached 49% by 1911. Almost half a million people – corresponding to 19% of the population – lived in the capital in 1911, compared with only 120,000 in 1840. By 1911 Aarhus had become the country’s second largest city, with 52,000 inhabitants, compared with 4,000 in 1840. A number of provincial towns had increased their populations to around 10,000.

Urbanisation was connected to overpopulation in the rural areas, where employment opportunities were lacking, and to the industrial and commercial development of the towns. Craft businesses and industry proliferated in the cities, where there was a more varied occupational structure and diverse labour market, along with generally higher wages. Urban growth also increased opportunities for work in construction, trade and services.

Economic development

The period 1840–1914 saw general economic growth interrupted only by short-term setbacks. After around 1880, agriculture became increasingly industrialised and new industrial enterprises emerged in the towns and cities. It was also at this point that the first multinational companies appeared in Denmark.

All sectors of the economy had to adjust to new conditions. Urban industries and agriculture were integrated in the market economy and thus exposed to the effects of market forces – which were not always positive. Seen over the entire period, there was a continual shift from agriculture to the industrial and service sectors. This went alongside a continual technological development, which affected industry in particular.

Agriculture remained an important sector throughout the period due to exports and foreign currency earnings, but by 1914 most of the country’s production value was created outside agriculture. Industry grew at the expense of agriculture, and became the most important sector for economic growth, together with the tertiary sector. The traditional structure of the Danish economy, in which the majority of the population was involved in food production and the country was largely self-sufficient, no longer existed. By the end of the period, Denmark had an advanced economy in which sales-oriented production was specialised and relied on the division of labour. This was the basis for the growing importance of the trade and service industry, which, along with the division of labour, is the mark of the modern capitalist economy.

The state and the economy

The state set the political framework for development. After 1814, the absolutist regime no longer attempted to control trade and industry directly. This was because the right to own property, which also applied in the countryside, had turned land into a commodity that could be traded freely. From the 1830s, a liberal policy was pursued, which emphasised the division of labour, free competition and the market economy.

At the same time, the absolutist government pursued a cautious policy in relation to the long-established rights of city merchants. The market towns’ monopoly on trade and the guilds’ monopoly on crafts were retained. In practice, craftsmen were able to establish businesses outside the market towns, even though it was forbidden, since this was seen as beneficial to agriculture. After the end of absolutism in 1848–1849, the liberal government did not feel bound by the vested rights of the merchants and guilds. With the Freedom of Trade Act (Næringsfrihedsloven) of 1857, it repealed the privileges of the market towns and guilds, marking the final breakthrough for economic liberalism.

Apart from this, the state played a hands-off role in the regulation of business and industry. It ensured the preconditions of economic growth through education, and, perhaps more importantly, by expanding infrastructure.

The integration of the country

The expansion of infrastructure in the form of roads, harbours, railways and postal and telegraph communication was a prerequisite for the development of a specialised and market-oriented economy. While at the beginning of the period there was only 8 Danish miles (approximately 51 km) of road with solid foundations in Jutland, by the end of the period there was an extensive road network across the entire country. Steam power was important throughout the entire period. Steamships connected Denmark to international markets and also linked areas of the country to each other, aided by the expansion of the railway network and steam locomotives.

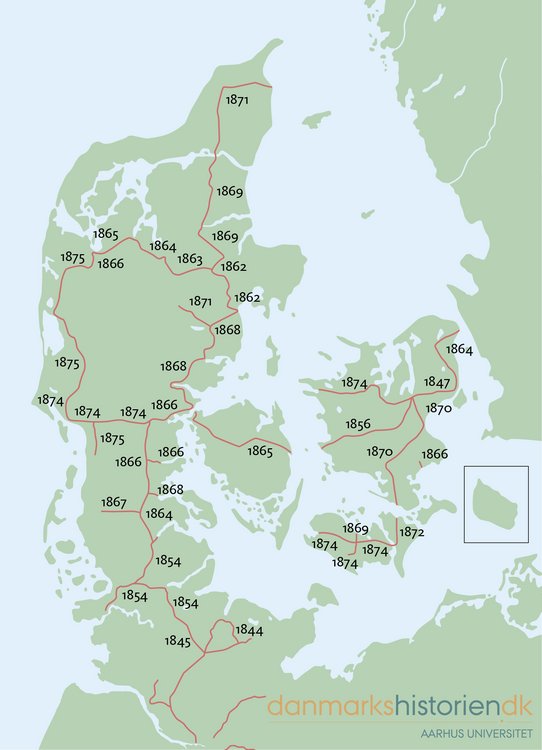

In 1847, the country’s first 37 km of railway opened between Copenhagen and Roskilde, and by 1870 most of the larger towns and cities were connected by 868 km of main lines. By 1910, local private railways had extended the network to 4,044 km. Railway ferries started operating between Jutland and Fyn in 1872 and between Fyn and Sjælland in 1883.

In 1868, a new state port was built in Esbjerg, underlining the state’s interest in promoting business infrastructure. As a consequence of its 1864 defeat, Denmark had lost Tønning Harbour in Schleswig, which until then had served as a shipping port for exports to Britain. With the expanding British market, the new harbour, which was connected to the railway network in 1874, became essential for sustaining Danish exports.

The Danish railway network, as it expanded between 1844 and 1875. The loss of Schleswig and Holstein following the war in 1864 cut off the southern part of the network, but it was expanded with several private lines after 1875. © danmarkshistorien.dk

Agriculture, 1814–1840

The period after the Napoleonic Wars was marked by economic crises caused by falling grain prices, which had a significant impact on the mainly grain-producing agricultural sector. A number of bankruptcies followed, but the sector survived the crisis by increasing its production and sales in the domestic market, where population growth had led to a rise in the demand for food commodities. The increase in production corresponded to the increase in population. At the same time, new markets opened in the Netherlands and Britain, where merchants from the provincial towns sold Danish products.

It was possible to increase grain production by improving the soil quality, cultivating new land and also growing new commercial crops – such as potatoes, clover and legumes – whilst retaining the same traditional technology. Animal production also increased, mainly to cater for the domestic market. The fluctuations that hit the agricultural sector came from the export market, which accounted for about 20% of total production in 1830.

Agriculture, 1840–1870

The years between 1840 and 1870 are known as the ‘corn period’ (kornsalgsperioden) in Danish history. Animal products for the domestic market still made up the majority of agricultural production, but there was major growth in grain production for the international market. The increasing grain prices were stimulated by the repeal of the Corn Laws in Britain in 1846.

In contrast to the previous period, the increase in production was now linked to new technologies in the form of new tools and machines, especially ploughs and harrows, produced by the dozens of iron foundries that were built in the Danish provincial towns. New methods to improve the soil were also employed, such as spreading lime, growing new crops and refining grain varieties. The establishment of the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University (Den Kongelige Veterinær- og Landbohøjskole) in 1858 was essential for promoting a more scientific approach to agricultural production.

Agriculture, 1870–1914

From the beginning of the 1870s, cheap grain from the USA and Russia led to a sharp fall in prices and ended the lucrative Danish trade in grain on the international market. The agricultural sector responded to this challenge by converting from grain to animal production. Grain was no longer exported but was instead used as animal feed; some feed was also imported for use in cattle production.

The income from animal production was largely used to construct industrial premises to process milk. The construction of new agri-cultural industries took place in close connection with the introduction of the co-operative business model as an organisational innovation. The first co-operative dairy was founded in 1882 and became the model for the hundreds of co-operative enterprises that followed. In 1909, there were 1,157 co-operative dairies in Denmark.

Co-operative dairies were established, managed and owned by producers, who agreed to deliver all their milk to the co-operative for a certain number of years. The members of the co-operative shared economic liability according to the number of cows they owned; in other words, both profits and losses were divided between the co-operative’s members depending on the number of cows they owned and supplied milk from. However, each member had only one vote at the annual general meeting, where strategic decisions were made.

The by-products from butter production were used for pig feed. This led to an increase in pig production, and bacon became a major export and a huge success on the British market. Between 1887 and 1914, forty-four slaughterhouses and pork-processing plants were built across the entire country, the majority of which were set up according to the co-operative dairy model.

The co-operative movement

The efforts of the farmers to organise themselves resulted in a network of associations, of which the co-operative movement (andelsbevægelsen) was a central part. In such economically precarious times, the co-operative model was the only financially sustainable way for farmers to operate their dairies. The farmers had no intention of leaving the processing of agricultural products to urban capitalists. Wealthy merchants from the towns attempted to get a foothold in the meat-processing industry, but they encountered fierce resistance from leading farmers, who were reluctant to allow outsiders to take profits.

Co-operative businesses were thus organised more democratically than the traditional capitalist business models found in the towns and cities. However, despite the principle of ‘one member, one vote’, the wealthier farmers (gårdmænd) dominated the management of the co-operatives; as major suppliers, they could quickly threaten the existence of the dairy if decisions went against them. Nevertheless, the fact that an increasing number of smallholders joined the co-operative dairies meant that all parties enjoyed economies of scale.

Savings banks and credit unions, also organised by the farmers and inspired by similar banks and unions in Germany, supported the co-operative movement economically. Their aim was to facilitate saving and to finance small land purchases and investments at low risk.

Modernisation of agriculture

The re-organisation of the agricultural sector entailed not only new co-operative institutions but also new technology for primary production and processing. Such technologies were promoted by farmers’ associations, which disseminated research results and new operation methods, and by agricultural schools, which trained farmers in more efficient, technological and long-term production. A system for knowledge collection and quality control was established, which was channelled back to the producers and ensured products of a high standard. Efforts were made to increase productivity through refining, better feeding and an increased use of fertilisers and agricultural machinery. Processes that had previously been carried out by hand were taken over by machines for sowing, mowing and threshing, in addition to harrows to remove weeds and new steel ploughs, which increased productivity within the animal feed industry.

In 1914, agriculture made up 60% of Denmark’s exports and accounted for most of the country’s foreign currency earnings; it was thus of great importance for the country’s overall economy. Livestock production quadrupled between 1870 and 1914. Pork production rose from 50 million kilograms in 1870 to 229 million kilograms in 1914. In the decade before the First World War, two products in particular – butter and bacon – accounted for two thirds of the agricultural sector’s production value and exports, with markets primarily in Britain and Germany.

Agricultural production became increasingly intensified, with an overall increase of 40% in yields per hectare between 1860 and 1914. During the same period, the area available for agriculture increased by 25%, due to damming, drainage and the cultivation of heathland. In terms of production, growth was massive and generated revenues that could be used for further investment in modern tools and production facilities. As such, the impact of livestock farming on the natural environment was huge, but there is no evidence that this impact – and its implications for nature and livestock – was discussed at the time.

Overall, the modernisation of Danish agriculture in the late nineteenth century gave Danish exports in semi-processed agricultural products a strong competitive edge in international markets, which accounts for agriculture’s very high export quota. At the same time it also made the country’s exports vulnerable in the long run due to this specialisation, especially when, from the 1930s onwards, agricultural markets were hit by increased protectionism.

Industrialisation in the provincial towns

Development within the agricultural sector was linked to small industrial enterprises in the provincial towns, which produced industrial processing equipment and agricultural machinery to support the continued industrialisation of farming. This machinery was often developed in England or the USA and presented to the Danish agricultural community by salesmen at various exhibitions around the country. This made it possible to produce local versions of the different machines at the factories that sprang up all over Denmark.

Smaller companies emerged, earning a profit from servicing and repairing the machines. Transport and service industries also had a markedly more significant role in creating value – a further indication of the transition to a capitalist society based on the division of labour and specialisation.

The Copenhagen business community

The business community in the capital operated according to a top-down model. Private investment banks put money into projects with potentially high profits and high risk. Inspired by the British model, companies were set up as joint-stock companies, where each shareholder was only liable for the capital originally invested, so that the investor did not lose everything if the project failed. C.F. Tietgen played a central role in the development of this sector. He became the director of Privatbanken (Denmark’s first investment bank) in 1857. His education gave him close ties to the British business and banking world; he also had an international perspective on the new business opportunities created by new technologies within the communication and transport sectors.

With Privatbanken behind him, Tietgen was the driving force behind the creation of the United Steamship Company (Det Forenede Dampskibs-Selskab, or DFDS) in 1866, which controlled steamships within Denmark and Danish shipping abroad. In many ways, DFDS was exemplary of developments after 1870. First, it was part of the transition from sail to steam, which was the dominant technological achievement of the period between 1870 and 1914, based on technological innovation, the economic climate and the ability of the shipping industry to adapt to new conditions. It was not until the end of the period that diesel-powered motor ships arrived, at which point the steamship fleet was five times larger than the sailing fleet, which had been almost totally dominant until 1850.

Second, DFDS was exemplary of the new type of company model and business strategy. Steamships were far more expensive to produce than sailing ships, and the joint-stock company therefore offered a solution. The business strategy was to acquire as many steamships as possible within a single shipping company. This would provide economies of scale, but it also had other advantages. Once the company had enough ships on relatively safe and income-generating domestic routes, it was possible to expand into the far more volatile area of international shipping. The former was designed to support the latter. As the wealthy company acquired new ships, it was able to offer new routes, and during the 1870s and the 1880s most of the small shipping companies were absorbed by DFDS.

DFDS also dominated sea routes to Britain, which increased thirteen-fold in the years up to 1890, due to the export of agricultural products from the new port in Esbjerg. In the 1870s, live animals were transported, but in the 1880s the focus shifted to butter, and from the 1890s to pork rather than live pigs.

This illustrates the growth and importance of the tertiary sector – that is, economic activities not connected with the production or processing of raw materials. DFDS served the agricultural sector, which provided the basis for huge growth, since transport was vital for the development of an international and specialised capitalist economy. Along with the railway and the telegraph, steamships created completely new conditions for trade and communication.

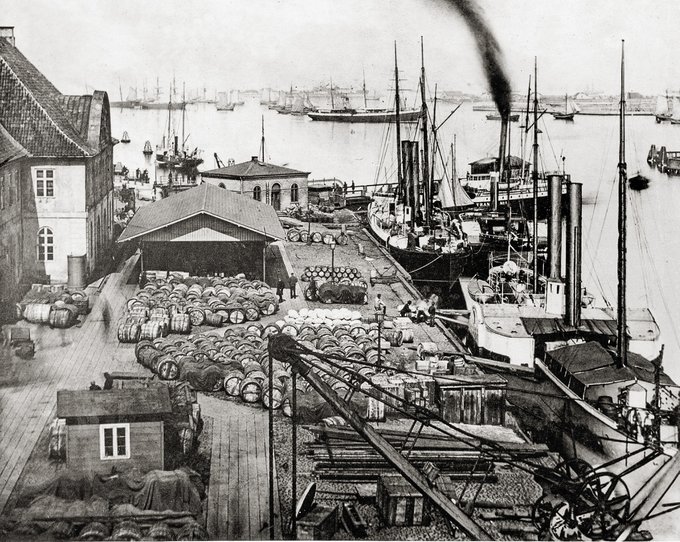

Søndre Toldbod (South Customs Station) in the port of Copenhagen, c. 1870. New types of ships are seen together with older ones, as the port continued to be the most important Danish hub for transport and the import/export of goods. At the quayside at the back is the steamship S/S Transit. The old paddle steamer at the front is most likely S/S Najaden. There are many sailing ships in the background. Photo: M/S Maritime Museum

Industry and internationalisation

The business model of international expansion from a domestic base was also used by the Great Northern Telegraph Company (Det Store Nordiske Telegraf-Selskab), which was founded in 1869. Located in a harmless small state on the fringes of Western imperialism, Tietgen managed – with the help of the Danish royal family and diplomacy – to secure large construction contracts in the face of competition from British firms. Tietgen also had the advantage of operating in a new and unregulated sector, which allowed him and Privatbanken to engage in financial transactions in ways that would later become illegal, and to provide information to investors as it suited him. This new industrial empire also included the Danish Sugar Factories (De Danske Sukkerfabrikker), which dominated sugar production, and the shipyard Burmeister & Wain, which became the largest industrial workplace of the period in Copenhagen.

A number of companies outside Tietgen’s empire followed the same model and strategy in the production of margarine, cement, cables and telecommunication. Many of these companies became multinational organisations on the basis of technological development, and engineering now became an essential, state-educated profession. It was this sector that carried the industrial revolution forward after 1870 and into the twentieth century. The period up to 1920 marks a heyday for Danish multinational companies, also by international standards.

Craft businesses

It is worth noting that large, industrial enterprises were the exception. Production in the towns and cities was characterised by many small artisan businesses. In the first official industrial census in 1897, the number of companies was calculated as 77,000 and the number of employees as 274,000 (including owners and salaried employees). One hundred and seventy companies had more than a hundred employees, which represented a doubling from 1870, but the vast majority were small workshops with a couple of employees.

Overall, craft businesses maintained their large share in the secondary sector. There was a great need for small building firms during the period, since the five-fold increase in the urban population meant more houses were required, and many large construction projects were launched in both the towns and countryside. Traditional manufacturing industries, on the other hand, began to decline in the face of competition from industrial goods and from cheap, unskilled – often female – labour. Weavers and basket-makers disappeared, the number of tailors decreased and shoemakers had to adapt to repairing factory-made shoes. Production in these areas became industrial and characterised by new methods, which typically required less labour, and by many innovations that gave rise to new professions, such as electricians and bicycle mechanics. Around the turn of the century, it was common for urban populations to ride cheap, factory-made bicycles, and bicycle mechanics are one of many examples of new trades that emerged at this time.

The Danish labour market and the September Compromise, 1899

The year 1899 was a pivotal one for the Danish labour market. The September Compromise (Septemberforliget) 1899 marked the culmination of the use of conflicts as a strategy for workers and employers to determine the price of work.

From the beginning of the 1880s, workers began to organise themselves in occupational trade unions. In the 1890s, membership of such unions increased dramatically; around 1899, they had a total membership of 96,000. Importantly, these locally based unions could also form part of a nationwide umbrella organisation: the Federation of Unions (De Samvirkende Fagforbund). In 1900, this federation consisted of 1,086 local trade associations affiliated to forty-one different national trade unions.

Employers organised themselves in a similar way, forming the Danish Organisation of Employers and Masters (Dansk Arbejdsgiver- og Mesterforening). The September Compromise was a settlement reached between the workers’ federation and the employers’ organisation, representing the conclusion of a major labour dispute from 1897 to 1899. During this period, two hundred work stoppages cost the workers around 13 million Danish kroner in lost wages and the employers around 3.1 million Danish kroner in lost working hours. The labour dispute culminated in a large-scale lockout in response to the workers’ strikes, affecting over half of all Danish trade union members.

The result of the September Compromise was that the employers’ organisation accepted the workers’ right to organise, while the union federation recognised the employers’ right to manage and allocate work.

The Danish labour market model

The September Compromise is often viewed as the starting point for the development of the Danish corporatist labour market model. In 1910, a labour market arbitration institution was established to mediate between parties when they failed to agree. This model resulted in a regulated labour market in which employers and employees entered into voluntary collective agreements, usually without state interference.

After the September Compromise in 1899, labour disputes thus played out in a regulated framework. Workers were united in respon-sible organisations that followed the rules of the game, and collective agreements were respected. Industrial disputes generally occurred in an organised and disciplined manner. But this did not mean that labour disputes ceased. In 1911, there was another large-scale lockout, brought under control within the framework laid out in the September Compromise. It is also worth noting that labour disputes moved from local to national settings. The historical pattern of Danish labour disputes thus followed a continued line of expansion: from a labour dispute in an individual workplace to local, regional and national disputes, and from disputes in single trades to disputes that concerned several sectors.

The rural community: estate-owners and farmers

The six hundred and fifty aristocratic landowners and their families constituted the top layer of the rural community. The 1849 constitution had removed all official privileges from the aristocracy, so the aristocratic landowner was simply a major landowner and producer operating under the same conditions as the farmers. However, in terms of wealth and prestige, the distance between estate-owners and farmers remained large.

Most aristocratic landowners understood the need to respond to the market, and they modernised their operations to exploit the favourable economic conditions after 1840. The sale of tenant farms generated additional income for the landowners. Their estates varied in size, but the larger ones had an extensive workforce of servants, smallholders and farm labourers, equivalent to a medium-sized business. Together, these estates employed as many workers as the whole of the industrial sector.

The landowning farmers (gårdmænd; singular gårdmand), who, along with their families, now occupied a total of 70,000 medium-sized farms across the country, also experienced a significant increase in prosperity. This group of farmers was mainly self-recruiting, since the custom was that the oldest son took over the farm.

Work on the farm was divided according to gender. This was nothing new, but these divisions gradually became more pronounced, as women’s roles in the home focused increasingly on the family and household spending, and men’s roles focused increasingly on production. The industrialisation of dairy farming moved women’s work away from the farm and rendered superfluous the work they had previously performed in butter production, for example.

The landowning farmers employed servants, smallholders and farm labourers to work for them. The relationship between the landowning farmers and those they employed became more contractual and official. It gradually became more important for these farmers to establish a distance between themselves and the underclass of the rural community, and to define themselves in relation to the estate-owners, civil servants and the better-off urban middle-class population. However, the notion of a common agricultural culture persisted for a long time as a result of the mutual dependence between landowning farmers and smallholders. As mentioned above, it was only after 1900 that the smallholders separated themselves politically from Venstre, which was dominated by the interests of the landowning farmers.

Rural society: smallholders and farm labourers

The landowning farmers constituted a minority in the countryside. Outside of this group were approximately 750,000 smallholders and farm labourers who gained only a limited share of the profit of economic growth, and whose lives were characterised by poverty and limited opportunities.

There were 160,000 smallholder families who lived on the edge of starvation, or occasionally below it. A quarter of smallholder families had enough land to support themselves, but the category of smallholder (husmand) included cottages with little or no land and some were therefore forced to seek work. They were all dependent on the labour their children could provide – children who were physically smaller and spent less time in school than those of the landowning farmers. The rapid growth of this class can be seen in the increase in the number of cottages to 212,000 by the end of the period. A quarter of these had no land attached. A total of 90% of the emigrants from the Danish countryside were sons of smallholders, who found opportunities for upward social mobility in the USA that were not available in Denmark.

The division of labour between smallholders and their wives was different. In order for the family to survive, it was necessary that everybody – men, women and children – contributed to the household. As soon as they were old enough, children were sent out into service, and absence from school was common. Unlike the wives of the wealthier, landowning farmers, the wives of smallholders were responsible for a large part of household production, and the men had to supplement their income by working for others.

A smallholding in Karup in central Jutland, between Herning and Viborg, 1895. The building was constructed in about 1884 as a farmhouse and barn. The picture shows owner Mads Chr. Nielsen with a horse and cattle and, to his left, his wife Ane and his three daughters and son-in-law. Mads supplemented the family’s low income by delivering post on foot between Viborg and Karup. The heather-thatched outbuilding on the right was used as a barn for sheep and hens. Photo: Local History Archive, Karup

Urban society: the middle classes

The wealthiest members of the middle class included businessmen, civil servants and the rapidly growing liberal professions, such as doctors, lawyers, dentists and veterinary surgeons. Groups such as bankers, engineers and businessmen expanded quickly as a result of the growth of large industries – a social elite that consisted of a few thousand people nationwide.

Around 1870, civil servants earned seven times as much as skilled workers, and businesspeople even more. They lived in large apartments or in detached properties on the outskirts of town, with carpets on the floor and oak furniture in the parlour. In the middle class, gender roles were clearly defined. The men went to work and the married women were housewives. The women made the home a welcoming place to be, and along with the housemaid they took care of the children and family life. Middle-class values played a key role in this way of life, primarily the idea that one had to manage for oneself. Respectability, cleanliness and self-discipline were prioritised, and the middle classes sought to disseminate these norms to the socially disadvantaged through philanthropic activities.

The lower middle classes traditionally consisted of minor business owners and those employed in service trades. During the last third of the nineteenth century a new social group of public servants emerged in connection with the development of the railway, the postal service, the police and the like. This group comprised approximately 140,000 employees, who enjoyed a secure livelihood and in many ways lived up to middle-class values. The number of small business owners increased steadily but doing business was often a fallback option for those who had not succeeded in agriculture or other urban vocations. The lower middle class was thus a heterogeneous social category that spanned both the materially well-off and the materially precarious.

Interior of the home of Chr. Bang, owner of an Aarhus oil factory, in Mejlgade, Aarhus, c. 1895. This was an urban, middle-class home furnished with heirlooms and modern furniture of the time. The middle class was far above the other classes socially and financially, but it was the upper part of this class whose lifestyle became the ideal for the urban middle class in general, the landowning farmers and the workers. Photo: Den Gamle By, Aarhus

Urban society: the working class

The working class earned their living through waged labour in the production of goods and services. It was a growing class, characterised by internal divisions between skilled workers – such as bricklayers and carpenters – and unskilled workers, and between the sexes. Only some of the skilled married men were able to earn enough for their wives to stay at home and fulfil the ideal of the housewife. In order to put enough food on the table, women most often worked outside the home, even though unskilled female labour was poorly paid. Even when both adults worked, money had to be saved wherever possible, and those with an insufficient income went hungry. This applied in particular to unskilled men and women and their families, since they were paid much less than skilled workers. Working-class women usually occupied the lowest-paid and least-qualified positions.

A working-class home in Ægirsgade in Nørrebro in Copenhagen, 1914. Better-off members of the working class enjoyed comfortable material conditions. Their clothes and house interiors were inspired by those of the upper middle class. Women and children often worked too. The women had a double workload, since they also took care of the home and children, which was not regarded as men’s work. Photo: The Workers Museum, Copenhagen

Poverty in the towns and cities

In some working-class districts in the industrial cities, families of up to six lived in one- or two-room apartments, with a shared privy in the backyard. Such conditions were most commonly found in Copenhagen, but they existed in other towns and cities as well, albeit on a smaller scale. The most disadvantaged lived in even worse conditions in basement and loft apartments, and in Copenhagen there were proper slums. There were also several impoverished tenement houses (fattigkaserner) in Copenhagen, where forty-five people lived in a space of one hundred square metres.

In 1853, 5,000 people died in a major cholera epidemic in Copenhagen, which highlighted the poor levels of sanitation for the most deprived in the city. Waste was disposed of through the street gutters, but the drainage was insufficient so sewage often built up. All sewage and rubbish was poured into the gutter – from butcher’s and tannery waste to the contents of chamber pots – and the gutters thus became an unparalleled source of infection. The understanding of contagion at the time was that infection was carried by germs in the air, which was used as the basis to improve the sewerage system. The cholera epidemic also gave rise to housing associations (byggeforeninger), which were set up to improve housing conditions for the urban working population, though these associations enjoyed only limited success.

Poverty was visible in the second half of the nineteenth century, and the mass poverty that came with urbanisation was as widespread in Copenhagen as it was in other European cities. From the servants and apprentices, it was only a small step to the people of the street, criminals, beggars, prostitutes and recipients of poor relief – all of those who lived on the fringes of the normal social order.

The development of Copenhagen: 1840, 1880 and 1920. The population grew rapidly during the period, while urbanisation meant that many people sought work and housing in the towns and cities. In 1840, approximately 120,000 people lived in Copenhagen; by 1911, this figure had risen to almost 500,000. In this way, the city expanded beyond its walls into new districts and suburbs. © danmarkshistorien.dk

Prostitution was nothing new, and had been punishable since the Reformation. However, it began to be regulated in the nineteenth century in order to limit the spread of syphilis. Such regulation was inspired by the situation in France and was applied unofficially in Copenhagen until it became law in 1874. Women who earned a living through prostitution were now forced to register, and were also subjected to regular medical and police checks that restricted their personal freedom. Servants and girls who supplemented their low factory wages with occasional prostitution also had to register. The law applied to all the women who sold their bodies, but no regulation was imposed on the men who bought their services, even though these men were just as likely to spread sexually transmitted disease. This reflected a clear, gender-defined double standard concerning sexual morality.