2. National conflict, war and neutrality

After the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, which ended the Napoleonic Wars for the Danish state, Frederik VI had to accept the cession of Norway to Sweden. If he wished to salvage the rest of his conglomerate state, there was no choice but to relinquish Norway. As compensation, Frederik VI became ruler of the duchy of Lauenburg and its 40,000 inhabitants.

In terms of military, population and resources, Frederik VI was left with a severely weakened state in 1814. The war itself had led to economic ruin, and the loss of the Danish fleet in 1807 meant that the composite state could not guarantee its own safety. The major European powers could no longer consider appealing to Denmark for military or political assistance. The continued existence of the kingdom as an independent state was dependent on the major powers valuing its existence.

The German Confederation and Holstein

At the Congress of Vienna, which took place between November 1814 and June 1815, the major powers determined the state borders of the future without consulting the representatives of the Danish king.

The most significant consequence for the future of the Danish composite state was Holstein’s membership of the German Confederation. Holstein had previously been a member of the Holy Roman Empire, which Napoleon had dissolved in 1806, and it was now made a member of the German Confederation, which was formed in Vienna in 1815. The federation was a relatively loose union consisting of thirty-five sovereign states and four city states, which, in principle, were obliged to support each other militarily in the event of war with external states. The dominant states in the confederation were Austria and Prussia. Holstein’s membership meant that distinguishing between Danish domestic policy and foreign policy in important situations was rendered meaningless.

In 1831, four advisory assemblies of the estates (stænderforsamlinger) were established, not because Frederik VI wanted them but because Holstein was a member of the German Confederation and he was therefore obliged to establish them.

The Three Years’ War, 1848–1850

The unclear distinction between domestic and foreign policy manifested itself during the war between the Danish and Schleswig-Holstein citizens of the composite state in the years 1848–1850. The war was the result of confrontations between the two national movements, both of which wanted a nation state.

The Danish movement, whose prime movers were National Liberals led by the jurist Orla Lehmann, wanted a nation state with a free constitution that consisted of the kingdom of Denmark and Schleswig. Their slogan was ‘Denmark to the Eider’ (Danmark til Ejderen), with the River Eider marking the border between Schleswig and Holstein. In contrast, the Schleswig-Holstein movement wanted a nation state with a free constitution for Holstein and Schleswig.

The National Liberals came to power at the fall of absolutism in March 1848, and implemented their policy. In response, the Schleswig-Holstein movement launched an armed uprising and formed its own government in Kiel. This resulted in the First Schleswig War, also known as the Three Years’ War.

The course of the war

In the initial phase of the war, the Danish army defeated that of Schleswig-Holstein, which then received assistance from the German Confederation and Prussia. This meant that the Danish army was put on the defensive, and following heavy fighting near the town of Schleswig it was forced to retreat to the north. Pressure from Russia stopped the advance of the German army, however.

The decisive factor that ended the participation of the German Confederation was that Russia ultimately put pressure on Prussia to make peace with Denmark, both on its own behalf and on behalf of the German Confederation. This occurred on 2 July 1850. Without the help of Prussia and the German Confederation, the war once again became a matter between the armies of Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. On 13 July 1850, a Schleswig-Holstein army of approximately 30,000 men crossed the Eider into Schleswig, and three days later 37,000 Danish troops entered northern Schleswig. On 25 July, the decisive battle was fought at Isted, between Flensburg and the city of Schleswig. The battle itself did not decide the war, but pressure on the Schleswig-Holstein government from Prussia and Austria meant that the Schleswig-Holstein army had to lay down its arms. The composite state was thus once again re-established under one sovereign, the Danish king Frederik VII, even though neither of the warring parties had wished for this outcome. The considerable loss of life had led to nothing. The war had killed approximately 2,100 and left 5,800 wounded on the Danish side; on the Schleswig-Holstein/German side there were around 1,300 dead and 4,700 wounded.

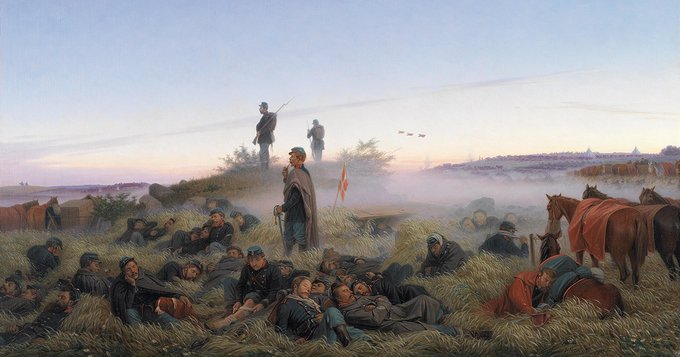

The morning after the Battle of Isted on 25 July 1850, painted in 1876. Some years after the battle, the painter J.V. Sonne (1801–1890) portrayed the victorious Danish soldiers with idyllic and nationalist undertones. From the 1840s, the Danish flag (Dannebrog) became a national symbol in middle-class circles. The volunteer soldiers from middle-class backgrounds were often motivated by national sentiment to take part in war. In contrast, the conscripted soldiers from the bottom layer of rural society were driven by loyalty to God and the king. Photo: National Gallery of Denmark

The composite state after 1850

The re-establishment of the composite state meant that neither of the two nation state projects could be realised. The major powers dictated that the composite state should consist of three separate parts: Denmark, Schleswig and Holstein. There were therefore no winners, a situation which shaped internal relations between the different parts of the monarchy after 1850.

Successive governments tried to find a constitutional form to make the state work, but without success. Once again, the unclear relationship between domestic and foreign policy came into play, as Prussia, Austria and the German Confederation took an active part in internal constitutional issues based on the membership of Holstein and Lauenburg in the confederation.

In 1858, the National Liberals once again formed a government in Copenhagen. Before 1861, the government tried unsuccessfully to establish a defence alliance with Sweden-Norway. After 1861, the idea of a composite state was abandoned and, instead, steps were taken towards realising the basic National Liberal idea of ‘Denmark to the Eider’.

The November Constitution 1863

On 13 November 1863, a joint constitution was issued for Denmark and Schleswig. The constitution of 1849 was not repealed, but a common council of the realm (rigsråd) was created to deal with issues pertaining to the two areas. Connecting Schleswig to Denmark in this way was a deliberate violation of the peace agreement that concluded the Three Years’ War. The government, the king, the opposition and all those in the political sphere were well aware that the November Constitution would result in war – and this put massive pressure on the National Liberal government. The Prussian chancellor Bismarck, backed by the German Confederation, threatened to move troops into Holstein if the constitution was not withdrawn. The new king, Christian IX, initially refused to sign the constitution and begin a war, and he tried to persuade conservative proponents of the composite state to form a government. It was only when this failed that he signed the new constitution. Envoys from France, Britain and Russia also tried to persuade the Danish government to withdraw the November Constitution in order to avoid armed conflict.

But the government upheld the constitution and, as such, opted for war. It is difficult to know why they made this choice. One possible reason is that there were no remaining options for compromise to resolve the opposing interests in the Danish composite state. In addition, the government counted on assistance from Sweden-Norway, even though they had no official alliance, and France, which had major power interests to nurture. It also seems that the prevailing feeling was that war was more or less inevitable. These factors are likely to have contributed to such a desperate move.

The war in 1864

The war began on 1 February 1864. The fortification known as the Danevirke – an extensive and symbolically significant system of ramparts built in the Early Middle Ages west of the city of Schleswig (see Module 1) – was designated as the battlefield. South of the Danevirke a deployment of 60,000 Prussian and Austrian soldiers was in place. The Danish army consisted of only 40,000 men. As early as 4 February, the army command decided that the Danevirke fortification could not hold and that the forces needed to retreat to the fortification in Dybbøl, 40 kilometres to the north. While the Danish troops fought at Dybbøl, 30,000 Prussian and Austrian troops marched through Jutland and occupied the country up to the Limfjord in northern Jutland, with the intention of exhausting Denmark economically.

On 18 April, the Prussians were ready for the final major attack. In the morning, the six nearest forts were bombarded with over 7,000 shells. At this point, 37,000 fresh and well-trained soldiers ran to their posts. The result was a devastating Danish military defeat with between 2,000 and 3,000 Danish casualties on the battlefield, 3,400 wounded and 1,900 missing. The Prussian losses were considerably smaller.

A ceasefire was subsequently agreed, and peace negotiations began in London. The main topic of these negotiations was how Schleswig should be divided. The Danish negotiators stuck to their demand that Schleswig should be divided south of Flensburg, which led to the collapse of the peace talks. Britain’s representatives had acted as mediators in the peace negotiations, and it was clear that Britain would not support the Danish demands militarily. On 26 June, the ceasefire ended. Approximately 30,000 Prussian troops crossed the narrow strait between Jutland and the island of Als, where 12,000 Danish soldiers were stationed. By the evening, the Danish troops had been forced to evacuate the island; they had exhausted their fighting power, and Britain’s position had shown that Denmark had no international support.

The peace treaty was concluded on 30 October 1864 and the victors dictated the conditions. Denmark had to cede the three duchies Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg, except for eight parishes south of Kolding, the island of Ærø and the area around Ribe, which the Danish state was allowed to keep. Disregarding the sparsely populated territories in the North Atlantic and the Danish West Indies, the conglomerate state had become a nation state, and the population identifying themselves as Danish in northern Schleswig had become a national minority in Prussia. With its 1.5 million inhabitants, Denmark was now one of the smallest states in Europe.

Prussian troops pose at the Danish fortification at Dybbøl after the battle on 18 April 1864. The 1864 war was one of the first to be documented by war photographers, but the technique was still dependent on long exposure times and therefore could not capture moving people or objects. For this picture, the German photographer arranged a line-up in front of Dybbøl Mill, which served as an observation and signal post for the Danish troops and was destroyed during the battle. After 1864, the mill was rebuilt and became a Danish national symbol, while the Germans erected several monuments and a cemetery in the area to mark their victory. Photo: The Gallery of the Danish Armed Forces

Foreign policy after 1864

Immediately after the war, Danish political life was marked by the fear of obliteration (undergangsangst) and the hope of recovery. Hope came from the prospect that northern Schleswig would be reunited with Denmark following a major European war that was expected to be imminent. In 1866, Prussia and Austria went to war. The Danish government offered Prussia an alliance in the hope of receiving northern Schleswig in return, but the offer was declined. At the peace talks in 1864, the French government, acting as a mediator, introduced the provision that the border in northern Schleswig should be revised following a referendum in the area. This Section 5 of the peace treaty gave the Danish hope, until Prussia and France went to war in 1870. France offered Denmark an alliance, but before the government could respond it received the first reports of a French defeat. The Danish government thus did not enter into an alliance with France.

The defeat of France was the last step in the unification of Germany under Prussian domination in 1871. The united Germany now became the dominant military and political power on the continent.

The events of 1870–1871 meant that Danish hopes of a recovery were shattered. After 1870, northern Schleswig became a matter between Denmark and Germany only. There were no longer any major powers which could be expected to support Denmark’s claim to northern Schleswig. When the German chancellor Bismarck decided to repeal Section 5 of the 1864 treaty in 1879, there was nothing that the Danish state could do. Consequently, after 1870, Denmark abandoned all attempts to forge alliances and returned to a policy of neutrality, which was viewed by all its politicians as the only way to keep the country out of future conflicts between major powers and to ensure its existence.

Højre’s policy of neutrality, 1879–1901

The question of how neutrality should be ensured militarily came to influence Danish politics until 1914. Between 1879 and 1901, the policy of the Højre (the Right – from 1915 the Conservative People’s Party) government was that Denmark should have the military force to hold off attacks until opponents of the aggressive party could come to Denmark’s rescue. The main part of this defence was to be a ring fortification system in Copenhagen (Københavns befæstning), an extensive and expensive system of cannon stations on strategically placed sea and land forts, and the capacity to flood areas in front of the city. Work on this fortification system began in 1886. The aim of the fortification was to protect the country’s political institutions and to give the government some room for manoeuvre in the event of war. Constructing fortifi-cations was a widespread defensive practice in Europe at the time and was therefore considered the best form of defence for a neutral state.

Another advantage of the fortification system was that the country could support it economically, while funding a nationwide defence was considered impossible.

Venstre’s foreign and defence policy, 1901–1914

In 1905, the question of defence led to the founding of Det Radikale Venstre, which literally means ‘the Radical Left’ but is often translated as ‘the Social Liberal Party’. This party had previously constituted the anti-military section of Venstre, which was the party of the Danish farmers and translates literally as ‘Left’. The Social Liberals believed the ring fortification system in Copenhagen and the military in general was a waste of money, and in the worst case a threat to neutrality, since it could provoke an attack from a major power. However, until 1909, it was Venstre which held power in government. This party had a more positive approach to military defence and also pursued a more accommodating foreign policy in relation to Germany.

This line was adopted in the hope that Germany would at some point voluntarily cede northern Schleswig to Denmark. This became relevant in 1909, when Denmark expanded its defence capabilities and augmented the fortifications in Copenhagen, albeit only on the seaward side. The expansion of the sea forts was interpreted as a re-orientation in foreign policy away from Britain and towards Germany, expressed also through diplomatic assurances that Denmark would never side with Germany’s opponents. It was not this German-leaning policy that ensured Denmark’s neutrality during the First World War, however, but rather the fact that Denmark was irrelevant to the military interests of the warring parties.

Policy of Neutrality in Germany's Shadow

In this film, Claus Møller Jørgensen discusses the Danish policy of neutrality and how it unfolded in the shadow of the rise of Germany as a major power. The film is in Danish with English subtitles and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.