3. Revolution, constitutional struggles and mass politics

The development of the two political-national movements mentioned in the previous section was connected to the creation of political spheres in the kingdom and the duchies, and the emergence of national thinking as a guide for political action.

The introduction of the advisory assemblies of the estates in 1831 played an important role in the early phase of politicisation. These assemblies created a political public sphere in which the organisation of society and the state was up for discussion. Yet there were limits to this discussion because the absolutist regime had strict laws on censorship. Despite confiscations and fines, censorship laws failed to prevent the development of a critical liberal opposition.

The emerging liberal opposition was made up of associations. Political associations were forbidden, so those that were created were either single-issue or civic educational associations. Political and informative communication took place through the most important mass medium of the time, the newspaper, which was a means to disseminate political and national views as well as to mobilise support for them. Newspapers provided the basis for the development of political life in the kingdom and the duchies, and they were mainly read by the urban middle class, especially in Copenhagen.

State and Society

Watch this film in which Claus Møller Jørgensen talks about the politicisation process after 1830, the end of absolute monarchy in 1848 and the dissolution of the composite state in 1864 as three central and interwoven elements in the history of the Danish state in the 19th century. The film is in Danish with English subtitles and lasts about nine minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The advisory Assembly of the Estates

The constitution of the Assembly of the Estates changed the absolute power of the King’s Code by introducing estate assemblies, elected by property-owners, to advise the absolutist government. The purpose of these assemblies was not to create a basis for the development of a political public sphere. As well as fulfilling his obligations under the peace treaty of Vienna 1814–1815, which obliged the Danish king as duke of Holstein to establish an assembly there, the king’s motives were defensive. In other words, the Crown sought to accommodate liberal forces by giving them a forum to express their opinions, and thus attempted to prevent the development of a strong opposition to absolutism.

The introduction of the estate assembly system in 1831 was linked to a revolutionary wave that swept across several European states, initiated by the July Revolution in Paris in 1830. Encouraged by the German Confederation, which considered it necessary to respond to the revolutionary events, advisory estate assemblies were introduced throughout the composite state, more as an expression of external pressure than of internal opposition.

There were four estate assemblies in total, based in Roskilde (covering Sjælland and Fyn), Viborg (covering Jutland), the city of Schleswig (covering the duchy of Schleswig) and Itzehoe (covering Holstein). The assemblies were advisory only, meaning that decision-making power was still in the hands of the king. They met for the first time in 1835. It was ultimately up to the king and his government whether or not they followed the advice of the assemblies, though often they did. A number of members were appointed by the king, and the rest were elected by the large landowners, urban landowners and wealthy farmers who owned land. The right to elect and be elected was based solely on the payment of land and property tax and was reserved for male heads of households. This was a corollary of the idea that different rural and urban vocations should be represented in order for the assembly to reflect the interests of the population.

In the kingdom of Denmark, the law meant that 50% of farmers did not have the right to vote, and that 90% were not eligible to stand for election. Only 3% of the population as a whole had the right to vote, but due to the property ownership requirement this fell to 1.4% in Copenhagen. Even fewer people could be elected. The same applied to the duchies.

Contrary to the intentions of the absolutist regime, the estate assemblies became a political platform for the Danish and Schleswig-Holstein national movements, which developed into a destructive opposition to the absolute monarchy and the composite state.

The Schleswig-Holstein movement

Until the late 1840s, the Schleswig-Holstein movement was a regional movement that wanted an independent Schleswig-Holstein in which the two duchies remained connected to each other within the framework of the composite state. On the one hand, supporters of this movement emphasised German language and culture, fearing the imposition of ‘Danishness’ and the centralisation efforts of the absolutist government during the Napoleonic wars. On the other hand, however, they wished to maintain a distance from the German countries and to remain a part of the Danish state. The ideal was that Schleswig-Holstein would enter into a personal union with the Danish kingdom and share the same king, making the region politically closer to Denmark but culturally closer to the German countries.

After 1831, Schleswig-Holstein regionalism was connected to the desire for a free constitution. The movement was rooted in the urban middle-class population; the city of Kiel with its university and its liberal middle class played a central role in the politicisation process and the creation of a newspaper-reading political public sphere in the duchies. The majority of people in the countryside remained indifferent or loyal to the absolutist government and king.

The Danish national movement

Copenhagen was the centre of the politicisation process and the Danish national movement in the Danish kingdom. The leading figures in the political public sphere were the National Liberals and the most influential newspaper of the time was Fædrelandet (The Fatherland), which was published from 1834. Associations, newspapers and journals that were vital to political life were founded in Copenhagen and reached out to the affluent and educated part of the middle class in the provincial towns.

The dream of extending Denmark to the River Eider was proclaimed in an 1842 speech by the most important National Liberal politician of the 1840s, Orla Lehmann. Following this speech, the main objective of the National Liberals’ policy was to create a nation state consisting of Denmark and Schleswig; this dominated their policy until 1864. The argument was based partly on the national principle that a large part of Schleswig was Danish-speaking, and partly on the idea that, historically and politically, Denmark and Schleswig formed one unit. The historical and political argument became decisive for the claim that, despite the German-speaking population in central and southern Schleswig, Schleswig in its entirety should be part of the future Danish nation state.

Absolutism and the national question

Political demands for a free constitution and a nation state were tightly intertwined in the national movements of the composite state. These demands represented a double challenge for absolutism as a form of governance and as a system of state formation. Christian VIII could not agree to a free constitution; nor could he accept that the composite state be reformed according to the wishes of the national movements. The king and his government thus perceived the movements as driven by partisan motives that created division and opposition instead of solutions based on reason.

Christian VIII equated people and language, believing that the language spoken on a daily basis should be the language spoken in all contexts. But this did not mean that the composite state was an ungovernable construction. On the contrary, it meant that the absolutist government had to pursue a policy that gave language communities the rights they were reasonably entitled to whilst respecting other language communities, and not least existing traditions.

It was the role of the absolutist government to strike the right balance between all these considerations. The government alone could achieve this balance, for only it could view the situation impartially without taking particular interests into account. It was irrelevant whether the members of government spoke Danish or German; what mattered was their work for the benefit of the composite state and the common good.

A.S. Ørsted, who was a central figure in the absolutist government from 1842, made this point in the state-sponsored Berlingske Tidende, the government’s most important medium and the kingdom’s most-read newspaper. It should be noted that support for the composite state, absolutism and nationalism was not confined to the political elite, but could also be found more generally among conservatives in both the duchies and the kingdom.

Schleswig and the language question

Leading figures in the emerging Danish national movement in northern Schleswig adhered to this conservative viewpoint until the Three Years’ War of 1848–1850. Others, such as Christian Flor, who was Danish and educated in Copenhagen, were National Liberals and had close connections to the National Liberals in the capital.

The Danish national movement appealed to farmers, because they were mainly Danish-speaking, whereas the urban middle class and civil servants generally spoke German. Aside from this, it resembled the other national movements, with its associations and its newspaper Dannevirke (published from 1838). Its main aim was to awaken Danish consciousness and protect the Danish language from the advance of German northwards.

However, many Schleswigians preferred to answer the question of nationality by claiming to be both Danish and German, instead of either Danish or German. This also applied to the Danish-orientated German-speakers in cities such as Flensburg, who wanted Schleswig to maintain its independent status between the Danish kingdom and Holstein. These people distanced themselves from both the Schleswig-Holstein movement and the Danish national movement.

Many Danish speakers in Schleswig shared a political goal with the duchy’s German speakers. They considered Danish their native language and valued it, but they also recognised the importance of their connection to Holstein and their position between Danish and German. Supporters of this Schleswig-oriented view therefore tried to avoid adopting a position in favour of one of the national movements. They wanted to remain what they were: Danish-speaking Schleswegians.

Polarisation after 1840

From the early 1840s, the national question attracted attention in public debates, and the issue became increasingly polarised. Between 1838 and 1842, the language question became politicised; as language ceased to be a matter of everyday practicality and became instead a decisive political issue and a marker of nationality.

There were three main actors behind the dynamics of this development: the Danish national movement in Copenhagen; the Schleswig-Holstein movement; and the absolutist government, which had to attempt to reconcile the opposition between the first two. Demands from the Danish movement sparked a response from the Schleswig-Holstein movement, from the absolutist government, or from both. This in turn triggered a new reaction from the Danish movement.

Increased polarisation led to a radicalisation of the two national movements, which made it impossible for the government to propose solutions that would not be interpreted as violations by at least one side. This polarisation culminated in 1846, when the government proclaimed in an open letter that the Danish royal family had succession rights in the Danish kingdom and in Schleswig in perpetuity, while the situation in Holstein was unclear.

This letter pleased Danish national circles in the kingdom and in northern Schleswig. In southern Schleswig, however, it triggered demonstrations and protest letters to the king. The assemblies of the estates in Schleswig and Holstein were dissolved prematurely in protest, and demonstrations in several towns – including one that required military intervention – reflected an unprecedented level of mobilisation and confrontation.

The open letter proved to be a disaster for the mood in Holstein. It alienated more of the population from the monarchy, and fuelled the demand for a German Schleswig-Holstein with as few connections to the rest of the Danish kingdom as possible.

The revolutions of 1848

On 20 January 1848, Christian VIII died following a short illness. He was succeeded by Frederik VII, who was generally recognised as lacking the personal skills to rule. Christian VIII had therefore provided him with a government that consisted of conservative members loyal to the absolutist composite state. On 28 January, the government made a public announcement that a new constitution was planned. This stipulated a new state constitution with a joint assembly, in addition to four regional advisory assemblies of the estates. The envisioned joint assembly was to handle issues concerning the composite state as a whole, with extended power and a modest democratisation of voting rights. The purpose of the change was to create unity and agreement across national dividing lines.

On 25 February, news of the revolution in Paris reached Kiel, and spread to Copenhagen the day after. Throughout February, the revolution spread to other European capitals, including Vienna and Berlin. In several places, war-like confrontations ensued between the military and protesters.

The news of the revolution opened up a window of opportunity that elevated political activity in Copenhagen to a new level. The pattern of polarisation between reaction and counter-reaction continued in an intensified form with almost daily demonstrations, mass gatherings, written protests and mobilisation. Polarisation also meant that the two national projects – the Danish national ‘Denmark to the Eider’ demand and the Schleswig-Holstein demand for an independent Schleswig-Holstein state, possibly as part of a united Germany – now had to be implemented, and no compromise would be accepted.

Revolutionary crisis in the composite state

The revolutions in Berlin and Vienna led activists in Kiel to begin to consider the unification of Germany as a real possibility, to which the Schleswig-Holstein project should commit itself. The future of Schleswig-Holstein lay not in being connected to the Danish state but in being part of a united Germany.

Several mass rallies were held in Copenhagen and the duchies. The moderate voices on both sides, who wanted to negotiate on the basis of law, were silenced. The newspapers played their part in raising expectations for a better future through the implementation of national and political projects, but mass rallies also showed what talented orators could achieve with the spoken word.

On 17 March, the Schleswig-Holstein movement demanded an independent Schleswig-Holstein with a free constitution and membership of the German Confederation – a demand that no government in Copenhagen would be able to accept. On 20 March, at a rally with approximately 2,500 participants in the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen, the Danish national movement demanded a free constitution for Denmark and Schleswig.

Frederik VII and the National Liberal takeover of power

At the beginning of his reign, it seems that Frederik VII was willing to reject the demands of the National Liberals and to uphold Christian VIII’s policy of preserving the composite state and absolutism. In the end, however, he decided that the era of absolutism and the composite state was passing. Nor did he have any desire to take on the role of absolute monarch himself.

This did not mean that the National Liberals were to join the government, or that a free constitution was just around the corner. The supporters of the composite state remained relatively strong, and negotiations with the National Liberals did not bear fruit. The situation changed only after Frederik VII received a letter from Kiel on 22 March and concluded that open rebellion had erupted in the duchies. This prompted the king to send for the National Liberal leaders. A government was formed led by A.W. Moltke, who was not himself a National Liberal, but recognised the merits of the points presented at the Casino Theatre rally. Of the nine ministers, five were National Liberals, with Orla Lehmann and D.G. Monrad as leading figures.

The March Ministry and the Schleswig-Holstein rebellion

The so-called March Ministry (Martsministeriet) was formed with the policy of ‘Denmark to the Eider’. In Kiel, a provisional government was formed for Schleswig-Holstein. This provisional government legitimised itself by appealing to the fact that, following the National Liberal takeover of power in Copenhagen, authority now lay in the hands of those hostile to the duchies. This meant that the legitimate ruler of the duchies, Frederik VII, could no longer act freely. The provisional government in Schleswig-Holstein therefore had to assume power in the king’s place and do its utmost to align itself with the cause of German unification and freedom. To prepare for an uprising, civilian militias were formed in the cities, and on 24 March the provisional government took over the military base in Rendsburg.

The allegation that the king’s hands were tied was necessary to convince the public in the duchies that it was legitimate to set up a provisional separatist government. Many royalists in the duchies were regionalists who wished to maintain a political connection to the Danish monarchy. Accordingly, there were strong forces prepared to side with the king. These included various individuals associated with the inner circle of power, in the state apparatus, and parts of the population in both the kingdom and the duchies.

The National Constituent Assembly

Upon appointment of the March Ministry, Frederik VII declared that he considered himself to be a constitutional king without absolute power. The government could therefore begin working towards a free constitution by calling elections for a national constituent assembly. The right to vote was extended to ‘respectable’ (uberygtede) men over thirty with their own household. These voters would elect one hundred and fourteen of the one hundred and fifty-two members of the assembly, and the remaining members would be appointed by the king. Elections for the assembly were held on 5 October 1848, while the war was still underway, and they resulted in an assembly that consisted of three almost equal factions: the Friends of the Peasants (bondevennerne), conservatives (helstatsmænd) and National Liberals (nationalliberale).

The most organised faction, throughout the election campaign and in the assembly, was the Friends of the Peasants, which had emerged as a political movement during the 1840s. They advocated democracy and suffrage for all men over twenty-five, a limited role for the king in decision-making processes and a one-chamber parliament.

At the other end of the political spectrum was an unorganised group of conservatives loyal to the absolutist state, such as A.S. Ørsted. They recognised the inevitability of a constitutional process, but they tried to avoid it becoming a slippery slope to democracy.

The third faction consisted of the National Liberals. In the constituent assembly created to draft a constitution, the division of roles and power was clear. The National Liberals, as a governing group, were accepted as leaders in the negotiations, and a draft constitution had to come from them.

Draft constitution

The draft of the constitution was written by D.G. Monrad and its language revised by Orla Lehmann. Monrad and Lehmann did not support the democratic one-chamber system advocated by the Friends of the Peasants. They believed that the parliament (Rigsdagen) should consist of two chambers, an upper house (Landsting) and a lower house (Folketing), with the Landsting acting as a conservative guarantee against majority rule in the Folketing. Extending voting rights too widely would be dangerous, since the majority of peasants was uninformed and impressionable.

The draft was directly inspired by the Belgian constitution from 1831, and also to some extent the Norwegian constitution from 1814. Characteristic of all the available models was the exclusion of women and the lower strata of society from the political process.

The June Constitution of 1849

On 5 June 1849, while the Three Years’ War was still being fought, the National Constituent Assembly adopted a constitution. The franchise for both chambers remained the same, meaning that only men over thirty with their own household could vote. In order to vote, these men were required not to have received poor relief or to have lost power of disposal of their property. Having their own household ensured their independence. As the head of the household, they represented the rest of the household, including their wives and their servants of both sexes. If a man over thirty ceased to be employed in service and gained his own household, he was given the right to vote. Women were excluded by virtue of their sex. The right to be elected to the Folketing was granted to men over twenty-five with the same restrictions as the right to vote.

Elections to the Landsting were indirect, and eligibility for election was limited to men over forty who, in the previous year, had paid 200 rigsbankdaler in tax to the state or the municipality, or who had an annual income of 1,200 rigsbankdaler. Socially this meant that voters were middle-aged men from the upper middle and upper classes. The idea was that men with this status would be more prudent, responsible and conservative than men with a lower income. By virtue of their economic status, they were expected to be in a position to serve the fatherland rather than their own interests. They would therefore be able to counter-balance or prevent hasty decisions made in the Folketing, which included members from more diverse backgrounds.

With the introduction of the constitution, approximately 15% of the population received the right to vote. This marked a break with the more restrictive status- and property-based franchise for the old assemblies, where only 3% of the population had the vote.

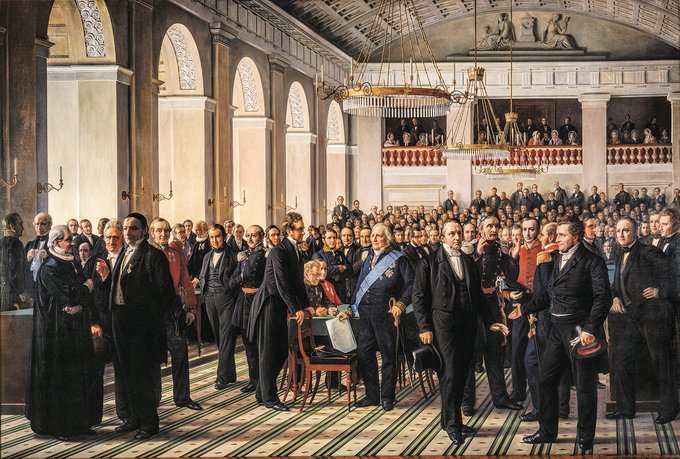

Constantin Hansen’s (1804–1880) painting of the first meeting of the National Constituent Assembly on 23 October 1848 was completed between 1860 and 1864. Some of the people depicted had died before the painting was finished, and Constantin Hansen also took artistic liberties with the composition. The National Liberals, whom he supported, were given a prominent place; Orla Lehmann, who can be seen in the foreground on the right, was not even a member of the assembly. Photo: Wikimedia Commons; original in the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle

King and parliament

The constitution provided for a three-part division of power between the judiciary, the legislature and the executive. Judicial power lay with the courts. Legislative power lay with the Rigsdag, and executive power lay with the king, who also shared some of the legislative power with the Rigsdag.

The king was intended to have a real function in the political process, especially in foreign policy. After a constitutional review in 1855, the Crown became the highest authority of the army and navy, but it also had a role in government and parliament. The king’s signature was required for a law to be passed, and Section 19 of the constitution stated that ‘the king appoints and dismisses his ministers’, which meant that a government could only sit for as long as it had the king’s support. The king thus had more power over the government than the parliament, which suggests continuity rather than change. The National Liberals understood the monarchy as working actively alongside the people’s representatives under a free constitution – a co-existence of royal and popular sovereignty.

The rest of the constitution’s one hundred sections dealt with a number of traditional freedoms such as a ban on arbitrary imprisonment, property rights, freedom of religion and the press, the right of assembly and the right to form associations. The context in which the constitution was written was reflected in its preamble, which stated the intention to introduce the constitution in Schleswig once the war was over. This never happened.

The 1848 revolution and its consequences

The war between Danish and Schleswig-Holstein citizens within the composite state lasted until 1850. When it ended, the great powers demanded the re-establishment of the composite state, though the June constitution was retained. This was in contrast to other parts of Europe, where constitutions were repealed and revolutions were suppressed with military force; it was due mainly to Frederik VII’s reluctance to assume the role of absolute monarch. Frederik VII did not take the lead in a military counter-revolution, which meant that, by virtue of its loyalty to the king, the military did not emerge as a counter-revolutionary force in Denmark. Over time, the officer corps had become increasingly composed of men with middle-class backgrounds, meaning that, unlike in other countries with aristocratic officer corps, it did not have the incentive to react to the removal of aristocratic privileges under the June constitution.

None of the national movements had achieved their objectives with regard to the composite state, but the war had mobilised wider sections of the population behind the national projects. This included those who were initially indifferent to the question of nationality, and, as in Schleswig, these people were forced to choose sides. The conflict and the national movements had thus created a deep rift between members of the composite state that had not previously existed. The aim of the Schleswig-Holstein project was clearly to become part of a united Germany, while the aim of the Danish national movement was to remain within a unified Danish state – with Schleswig but without Holstein.

The nation state, politicisation and national integration after 1864

The war in 1864 created a Danish nation state, but one without Schleswig and its Danish-speaking population. This nation state became the framework for continued politicisation, though the national question was no longer its focal point.

The years after 1870 saw the emergence of political parties – as well as the creation of channels for political communication through newspapers connected to these parties – and the establishment of a political culture with rallies and processions, particularly in celebration of Constitution Day on 5 June.

As political communication became socially broader, a larger section of the population began to take part in national politics. At the same time, parties directed their political activity towards various social classes and groups, supporting individuals’ awareness of belonging both to a particular social group with specific interests and to the Danish nation.

Politicisation became part of a national integration process that strengthened the awareness of being Danish. Schools played an important role in this process, since children learned about national history and literature, while the country also became more connected by roads, railways and steamships.

By 1864, national thinking extended beyond the urban middle class to include farmers, who had shown little interest in nationality or national issues before 1848. By 1914, nationality had apparently become universal, as a way for individuals to orientate themselves in the world.

Constitutional review, 1864–1866, and the revised constitution, 1866

The politicisation process had activated a group of large landowners who were sceptical about popular participation in politics. After 1864, the opportunity arose to roll back the peasantry’s potential majority power and to secure the influence of large landowners, which they believed they were entitled to by virtue of their property and taxes. With the creation of the landowners’ association (Grundejerforeningen) in 1843 and further subsequent associations, a group of politically active landowners was formed; they came to play a crucial role in the revision of the constitution in 1866 and formed the backbone of the political party Højre (the Right) until 1901.

The parliamentary basis for the revision of the constitution was secured by the National Liberals, who were similarly worried about what could happen if the uneducated general population gained political power. There was also a group of politicians from the group known as the Friends of the Peasants, who wished to establish a political alliance based on the common interests of the rural community. Shortly after the constitution was introduced, however, this alliance ceased to exist.

Demands for reform led to the Revised Constitution in 1866. As far as the Folketing was concerned, the Revised Constitution retained many of the basic provisions of the June Constitution from 1849. The most significant revision was that the Landsting was changed in order to safeguard against a possible peasant majority, or ‘smock-wearing absolutism’, as it was called in conservative circles.

The composition of the Landsting was changed so that twelve of the sixty-six members were appointed by the king (in practice the incumbent government). A complex set of election rules was drawn up for the remaining seats, which gave the country’s 1,000 wealthiest landowners special voting rights. This ensured that the Landsting became a chamber of landowners and that the incumbent government was able to stay in power for as long as it had the support of the king. This arrangement provided the basis for a government that lasted until 1901, under the leadership of landowner J.B.S. Estrup until 1894.

Political parties and politicisation

As mentioned above, politics assumed a modern character after 1870 with the formation of political parties, associated organisations and a partisan press based on the so-called ‘four-party system’. Actually only three parties were involved: Venstre, Højre and the Social Democrats. In practice, however, Venstre consisted of two groups: Det nationale Venstre (the National Liberals) and Det europæiske Venstre (the European Liberals), the latter of which formed the basis of Det Radikale Venstre (the Social Liberals) in 1905.

Political activity now became organised. Local electoral associations were formed, which nominated a candidate whom the party worked to get elected. In the years after 1870, this created an intricate network of political associations in the countryside and towns.

Political participation and its relevance had to be learned, just like identification with the national community. This took time. At the election in 1855, only 15% of the 135,000-strong electorate voted; in the 1860s, this figure rose to between 30% and 40%, and in the 1880s it reached 70%. This eventual mobilisation of the electorate was connected to a significant expansion of the political public sphere, which was primarily driven by the newspaper as a medium. In the period after 1880, the majority of the Danish population read a newspaper as part of their daily routine, which signified a democratisation of access to culture and politics. Political knowledge and debate were spread through the so-called ‘four-paper system’ (firebladssystem), where each party had its own associated newspaper. These newspapers mainly discussed politics, but they also contained information on all the major and minor events of the day. In 1914, the four-paper system reached its peak with two hundred and forty-one newspaper titles. Some were national publications based in Copenhagen, but most were local editions of titles such as Socialdemokraten (The Social Democrat).

Venstre

Det Forenede Venstre (the United Liberals) was founded in 1870 and enjoyed a majority in the Folketing for most of the period. The two strands of the party – the national or Grundtvigian, named after the pastor and national poet N.F.S. Grundtvig, and the European (or radical) – were strongly critical of one another. Although they agreed on democracy, parliamentarianism, private property rights and civil rights, they were plagued by internal divisions, particularly concerning the question of defence. The party’s campaign issue was the parliamentary principle: that no government could remain in power if they had a majority opposing them in the Folketing.

The national or Grundtvigian strand wanted the electoral provisions from the 1849 constitution reinstated over the provisions in the 1866 constitution, and the party gradually came to advocate giving women and servants the right to vote and be elected. This strand of the party also campaigned for economic liberalism and limited state expenditure, although they acknowledged the importance of building up military defences against Germany.

The national strand of Venstre had its electoral base in the countryside, especially among the farming community. At the election in 1913, Venstre won forty-four of the one hundred and four seats in the Folketing. In the 1880s and 1890s Venstre was led by Frede Bojsen and Chresten Berg. J.C. Christensen led the party into government in 1901; like Chresten Berg, he was a schoolteacher.

The leadership of the party was divided over whether to negotiate with the Højre government, which Bojsen supported and Berg and Christensen opposed. Bojsen reached a settlement with the government in 1894; in 1895 Christensen formed the Venstrereformpartiet (the Venstre Reform Party) without him.

The European strand of Venstre consisted of democrats who believed that political citizenship should include the entire adult population. They were closer to the Social Democrats in their views on the social question than their national or Grundtvigian counterparts. They regarded society as characterised by class oppositions, and considered it the state’s responsibility to reduce class tensions and ensure better conditions for the least well-off classes. The ‘Europeans’ were anti-militarist and did not believe in military re-armament. As mentioned above, in 1905 the European strand seceded from Venstre to form Det Radikale Venstre (the Social Liberals).

The ‘Europeans’ mobilised support from Copenhagen intellectuals and rural smallholders, who thus became politically mobilised around 1900. In 1913, the Social Liberals won thirty-one seats in the Folketing. The party’s leading figures were the university-trained academics Edvard Brandes and, until his death in 1902, Viggo Hørup.

The Social Democrats

The Social Democratic party (Socialdemokratiet) was founded as a branch of the International Workers’ Association (Den Socialistiske Internationale) in 1871 and saw itself as a party for the working class. Especially in its early years, the social democratic movement encountered scepticism from parts of the middle class and the authorities. Socialism was seen as a revolutionary movement intended to overthrow existing social powers through violence. Despite the imprisonment of its leaders following police officers’ violent dispersal of a demonstration known as the Battle of the Common (Slaget på Fælleden) in 1872, the Social Democrats became an accepted part of the political landscape relatively quickly. Their aim was to eliminate political and social inequality, to improve the living and working conditions of the workers and, in the long term, to create a socialist society in which the means of production were shared. The state was to play an active role in this project; in order to secure power over the state, the party assumed a parliamentary approach. Its 1876 manifesto stated that men and women over the age of twenty-two should have the right to vote and that the battle for democracy and parliamentarianism was the party’s main priority. The Social Democrats were anti-militarist and advocates of international understanding between countries.

The party mobilised urban workers in particular. In 1884, it won two seats, making it the smallest party in the Folketing, but by 1913 it had thirty-two seats. Until 1910, the Social Democrats were led by P. Knudsen, who came from the Jutland town of Randers and was a glove-maker by trade.

Højre (the Right)

Højre was the conservative party representing landowners and former National Liberals. The cornerstone of conservative politics was the right to own private property. Landowners had entered politics in order to protect this right and to prevent a popular majority depriving them of their land. They emphasised the role of the monarch as the custodian of the common good, and had little to say in favour of democracy or parliamentarianism. They supported rebuilding the military, especially the fortifications in Copenhagen, which they thought would safeguard Denmark against the Germans and arouse a sense of national pride in the population.

The party mobilised support among the landowners, but also at times from the middle and working classes in the towns. In its heyday in the 1870s, it had around forty-five seats in the Folketing, but by 1913 it was in crisis, with only seven seats. Until 1894, Estrup was the undisputed political leader of the conservatives, though his cousin Jacob Scavenius also assumed a prominent position in the party. Both were landowners.

The constitutional struggle, 1875–1901

The ‘constitutional struggle’ (forfatningskampen), as it is usually called, concerned the distribution of power between the Folketing, dominated by Venstre, and the Landsting, in which Højre had a majority. Venstre believed that power lay in the Folketing and that the government should reflect its composition. The incumbent Højre government believed the government had a mandate from the king and could remain in office for as long as it had the king’s support.

In 1877, the two houses of the Danish parliament were unable to agree on a final version of the Finance Act. Estrup therefore suspended parliament and issued a temporary or provisional Finance Act, which authorised the government to collect taxes and to allocate state funds to those areas already approved by both houses. As such, the provisional Finance Act did not transgress the decisions already taken by parliament.

However, the issuing of this act marked the beginning of an irreconcilable power struggle between the Estrup government and Venstre in the Folketing. The issue of defence and the Copenhagen fortification were central to this conflict. At the beginning of the 1880s, the leader of Venstre, Chresten Berg, used the ‘politics of obstruction’ (visnepolitikken) to attempt to halt legislative work in order to force out the government, but he was unsuccessful. In response, the Estrup government became increasingly dictatorial in what resembled autocratic rule.

During the years 1885 to 1894, Estrup suspended the Rigsdag every year before the conclusion of the Finance Act negotiations and governed on the basis of the provisional Finance Act without parliamentary backing. Estrup and his government thus decided how state revenue should be spent without the Rigsdag, sidelining the legislature. The largest expense, amounting to 41% of the budget in some years, was spent on the fortification of Copenhagen, which was hugely controversial both in the Rigsdag and among the general population. For Estrup, the fortification could be used not only to fulfil his military policy but also to create divisions among the opposition. Members of Venstre were united in their opposition to Estrup but divided on the issue of defence. The fortification therefore became the focal point of the ongoing constitutional struggle; it created general mistrust between the government and the political parties, and divisions in the population.

The political situation resulted in a surge of political activism, including mass demonstrations on Constitution Day directed against the Estrup government. 100,000 people took part in such an event in Copenhagen in 1885. Rifle associations were established and people were encouraged to withhold tax. The government responded by banning state employees from being politically active, setting up a military police force and punishing instances of inciting agitation in the press.

Constitutional Struggle and Mass Politics

Watch this film in which Claus Møller Jørgensen talks about the constitutional struggle and fundamental changes in political life and parliament (Rigsdagen). The film is in Danish with English subtitles and lasts about nine minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The social state

Social legislation was introduced in the early 1890s. Scholars use the term ‘social state’ to denote the limited way in which the social consequences of the self-regulating economy were corrected. The first social insurance legislation was adopted in 1891–1892, as the first results of collaboration between Det nationale Venstre and Højre. The initiators agreed that people were not to blame for the economic problems they faced. They were thus deserving of help, and should be supported without forfeiting the right to vote. In addition, a general increase in prosperity made it easier for individuals and the state alike to contribute to social security. Social insurance inspired by German legislation was also seen as a means to limit the increasing influence of the Social Democrats among the workers.

Under the new legislation, those over the age of sixty classified as the ‘deserving poor’ had the right to old age relief without loss of political rights. State support for sickness insurance provided some degree of security for those unable to work because of illness. The Poverty Act (Fattigloven), which was essentially a codification of earlier legislation, was limited in scope but extended eligibility for assistance. Overall, the social insurance legislation of 1891–1892 meant that greater numbers joined the category of the deserving poor, and the state assumed responsibility for addressing the social question.

Social insurance schemes were organised by civil society, but the state part-funded individual contributions to schemes for accident insurance (1898) and unemployment insurance (1907). This co-funding system was designed to increase security while ensuring that the individual still bore some financial responsibility.

Another area in which the state played an active role was providing cheap loans to enable people to set up smallholdings. Through legislation enacted in 1899, the state guaranteed such loans in an attempt to stem the migration of labour from the countryside to the towns. However, the owners of the new smallholdings were still expected to earn a significant part of their living working for others, since the smallholdings themselves were too small to support a family. The intention behind this initiative was that farm workers would have enough land to cultivate crops to support their household, and a labour force would be secured for landowners and farmers. The political aim was to reduce social tensions in the countryside and to prevent the spread of socialism.

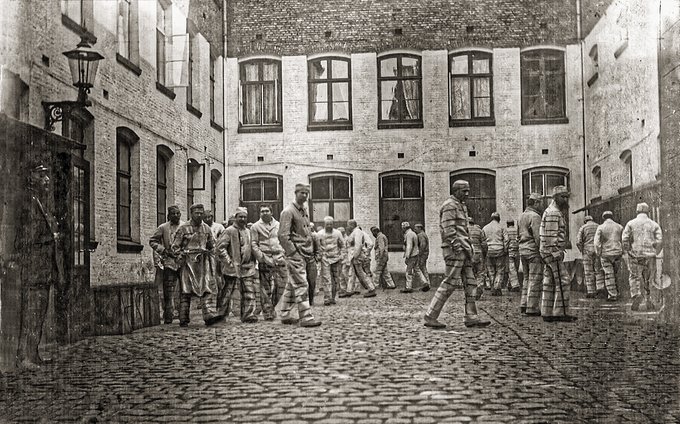

Daily exercise for the ‘paupers’ in the Ladegården workhouse, near the lakes in Copenhagen, around 1900. Ladegården was established in 1822 and housed the poor, homeless, disabled and sick, who were obliged to work in return for their food and lodging. Inmates of the workhouse lost their civil rights: the right to vote and own property, custody of their children and the right to marry. In 1908, Ladegården was replaced by Sundholm on the island of Amager. Photo: Royal Danish Library

The first Venstre government, 1901

The constitutional conflict came to an end in 1894 with a settlement between the conservatives, who believed Estrup was becoming too autocratic, and the moderate (national) Venstre, who were prepared to vote for military spending. This settlement required Estrup to step down as leader of the government. The two groups began – and continued – to collaborate on social legislation.

The settlement in 1894 meant that Estrup stepped down, but Venstre did not gain power. Instead, it split following the formation of the Venstre Reform Party, led by J.C. Christensen. He and the majority of Venstre viewed the settlement with Højre as a betrayal. Even though the Venstre Reform Party won a majority in the Folketing in 1895 and again in 1901, it was unable to persuade Christian IX to let J.C. Christensen form a government, despite the fact that the party had seventy-six out of one hundred and four seats in the Folketing, while Højre had only eight.

Although Venstre had long had a solid majority in the Folketing, it was actually a group of conservatives, frustrated at what they saw as an unsustainable political situation, who recommended the party to the king in 1901 and thus brought it into power. A few months after the catastrophic conservative defeat in the 1901 election, King Christian IX dissolved the conservative government and appointed a Venstre one, albeit headed by the politically unaffiliated – and thus acceptable – J.H. Deuntzer, who was a law professor.

The first Venstre government in 1901 is often referred to as the ‘System Change’ (Systemskiftet) in Danish politics, because after this date parliamentarianism in the Lower House was accepted as the principle for forming governments, even though this was not enshrined in the constitution until 1953.