1. The Danish kingdom

From 1814, the kingdom of Denmark was part of the absolutist king’s realm – a conglomerate state, which in addition to the kingdom also included the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg. In the present module, this will be referred to as the ‘composite state’. The extent of the state was determined not by the language or culture of the inhabitants, but by the territory over which the monarch had sovereignty. Several languages were spoken in the composite state. The two most prevalent were Danish, which was spoken in the kingdom itself and in northern Schleswig, and German, which was spoken in southern Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

The composite state was governed by the king, who bound the state together as a common point of reference. Loyalty, rather than uniformity, was the aim of the state project. In addition to this, the Danish monarchy also ruled the colonies of Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) and Serampore (now part of Kolkata) in India and trading posts on the Gold Coast of Africa (now Ghana), the Danish West Indies (now the US Virgin Islands), and the dependencies Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Iceland.

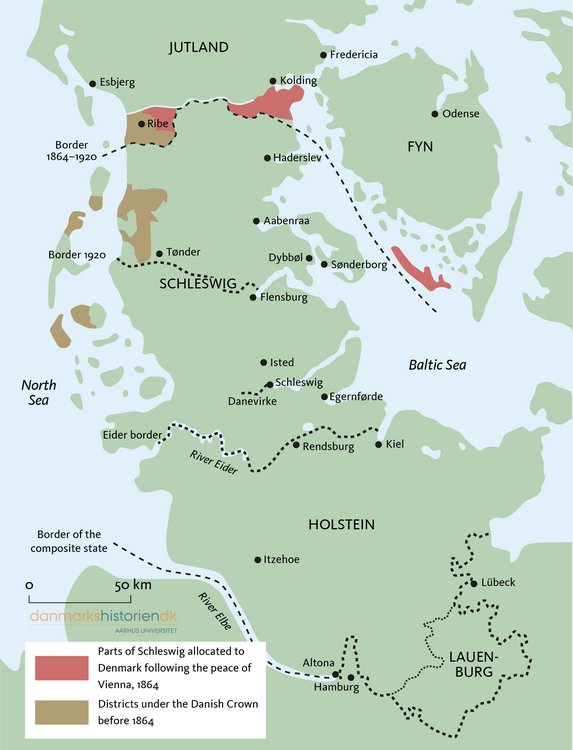

Schleswig and Holstein and their borders with the Danish kingdom in 1864 and 1920. In the Middle Ages, the River Eider marked the border between the duchy of Holstein and the Danish kingdom; in the nineteenth century, it came to play a political role as a slogan in the Danish argument for including Schleswig in the Danish kingdom. The borders of the composite state marked the extent of the Danish monarchy’s rule between 1814 and 1864. The two upper lines on the map show the border after the war in 1864 and the current border following the referendums in northern Schleswig in 1920 respectively. From a Danish perspective, these demarcations reflect a process whereby the Danish-speaking Schleswigians in the north of the duchy went from identifying regionally as Schleswigians to identifying nationally as Danish. © danmarkshistorien.dk

The period 1814–1914

This module explores the period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars – which as far as Denmark was concerned occurred in 1814 – and the beginning of the First World War in 1914. Following its involvement in the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden at the regional peace treaty of Kiel in 1814; Norway thus ceased to be a part of the Danish kingdom for the first time since the Middle Ages. The cession of Norway, combined with the loss of the fleet in 1807, meant that the composite state became a small state. It also meant the end of the monopoly on the trade in grain in southern Norway. At the same time, new trade connections were established with the Netherlands and Britain, which led to a re-organisation of foreign trade. Culturally, however, the connections between Denmark and Norway lasted throughout the century.

The end of the period in 1914 was marked by the beginning of a new European and global major war, the First World War. From a Danish perspective, the century 1814–1914 was also defined by the pivotal events of 1864, when military defeat and the loss of the duchies meant that Denmark became a nation. The presentation of political history in this module is also shaped by these events. In the years before 1864, emphasis is placed on the political-national movements in the composite state, which eventually led to its collapse, while in the years after 1864, the focus is on political developments in the Danish nation state.

Long-term economic and social changes took place relatively independently of the wars. The decades after 1814 were affected by economic crises caused by Denmark’s participation in the Napoleonic Wars, but these crises proved relatively insignificant in the long term. Longer-term developments, including urbanisation and population growth – from 900,000 in 1800 to 2,700,000 in 1910 within the kingdom of Denmark – as well as the modernisation of infrastructure and agriculture, the emergence of industrialisation after 1870 and a re-ordering of society, continued throughout the nineteenth century.

The colonies

The rationale behind the Danish colonies was purely economic. The Danish state was interested in the colonies and their populations only as long as they could make money from them. This was the case for both the slave-based colonies in West Africa and the Danish West Indies, and the trading stations in India. When it became clear that the African and Indian colonies were no longer profitable, they were sold to Britain, an expanding imperial power, in the 1840s.

The exception was the Danish West Indies. Although these islands also made a loss, it was impossible to find a buyer for them despite several attempts made after 1867. The enslaved population was emancipated after a rebellion in 1848, but as the century progressed their living conditions deteriorated rather than improved. The Danish state ceased to regulate the treatment of the emancipated slaves; nor did it invest in education, hospitals or infrastructure, since the islands did not yield any returns.

Greenland received only modest attention from the Danish state – a situation that only began to change after the start of the twentieth century. Colonial policy in Greenland was based on maintaining the Danish trade monopoly, the Christian mission and the insistence that Greenland remain a nation of seal catchers. Nevertheless, Danish presence changed Greenlandic society, partly by creating a Danish upper class and partly because the Inuit population of around 11,000 people increasingly began to settle in the twelve colonial towns, which led to social problems.

Iceland’s position was significantly different. It was defined by a marked independence movement after 1830, which resulted in a gradual extension of the island’s autonomy at the same time as commercial modernisation was taking place in areas such as agriculture, sheep farming and sea fisheries. The Faroe Islands were in a similar position to Greenland, but here the abolition of the Danish trade monopoly in 1856 also led to commercial modernisation, just as it had in Iceland. At the end of the century, a national revival emerged which emphasised Faroese cultural identity. After the turn of the century, two political camps were formed with opposing views on whether the future of the Faroe Islands should take place with or without constitutional links to Denmark.