5. Religion and culture

The religious life of the Late Middle Ages has often been interpreted negatively, in the light of the Lutheran Reformation that followed. Not only have the Church and the clergy been portrayed as corrupt and depraved, but the religiosity of the wider population has been described as superficial, institutionalised and materialistic in contrast to the more internal and personal relationship to God that came with Lutheranism. New research has departed from this view.

Religious life and Church reforms

The Church undoubtedly underwent a number of crises in the Late Middle Ages. It was weakened and increasingly secularised as a result of initiatives by the king and the nobility to limit its independence. But the development of the Church was also characterised by reforms, intended to remedy depravation and corruption. It was not possible to reform the papacy itself, but limited and local reforms continued after the collapse of the major reform councils in the mid-fifteenth century. Among other things, attempts were made to improve the behaviour and morality of the parish priests and cathedral chapter clergy. There were also considerable efforts made to reform the monasteries. Such initiatives often came from the old monastic orders themselves, while at the same time completely new orders were founded, which quickly became popular. The reform initiatives were supported by the monarchy (not least the queens), the bishops and the nobility, both out of a sincere desire for reform and also because it allowed them to influence the monasteries and to hold a share in the popularity of the reform movement.

Popular religiosity

Alongside the many Church reforms, religiosity flourished among the general population. One common denominator of many of the outgrowths of late medieval religiosity was that forms of faith that had previously been reserved for the clergy were now adopted by the lay population. For example, the Liturgy of the Hours (prayers recited at specific times of the day), which had hitherto been confined to monastic life, was now taken up by particularly religious people outside the clergy estate. Lay people went from being passive spectators to active participants in living a life of piety, and it is therefore possible to speak of a democratisation of religiosity in the Late Middle Ages.

There were many reasons for this development. An underlying factor was the economic and social processes following the Black Death. This created more self-aware burghers and peasants, who wished to increase their influence over their own material and spiritual life. The crisis within the established Church and the widespread dissatisfaction with the clergy also played a decisive role. Many felt they had to take matters into their own hands, and the relative flexibility of the late medieval Church left room for private religious ventures. In some cases, the inspiration even came from well-established ecclesiastical institutions. The mendicant orders, who participated in wider society to a greater extent than the old orders, played a particularly important role in spreading a Christian life of piety to all layers of the population. One of the main activities of the Dominicans was to preach the word of God in the vernacular, which is why they were also referred to as the ‘preaching brothers’, while the Franciscans worked to promote ordinary people’s use of the confessional.

An important aspect of religious revival in the Late Middle Ages was mysticism. This trend focused on the feelings of the believer for the divine, and its ultimate goal was the mystical union of the individual with God. In the Late Middle Ages, people who were in direct contact with God in this way gained great popularity; they were often women. In the Nordic region, Birgitta of Vadstena (St Bridget of Sweden, c. 1303–1373) became extremely important. Birgitta had experienced a vision in which she entered into matrimony with Christ, and she received regular revelations from Him. In 1370, she founded a monastic order, the Bridgettines, and she was canonised in 1391. In Denmark, the Bridgettine monasteries Maribo and Mariager were founded in 1416 and 1446 respectively. The worship of St Birgitta of Vadstena was supported by the Danish monarchy, who wished to make her a saint of the Kalmar union.

Piety, penance and indulgence

The Black Death and the subsequent epidemics were a major driving force behind the late medieval religious revival. The plague was perceived as God’s punishment for the sins of the people. The individual was left in existential fear of God’s wrath, not only in his or her worldly life, but also in the afterlife. One feared not only the eternal loss of the soul to the torment of Hell but also the flames of Purgatory, where the sinful soul had to be purified before it could potentially enter Heaven. Many religious activities were therefore concerned with avoiding Hell and shortening time in Purgatory.

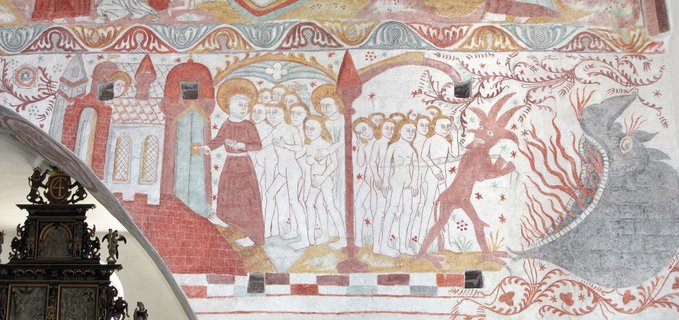

The devil leads sinful souls to Hell, while a monk or saint leads the pure to the gates of Heaven. Fresco in Fanefjord Church on the island of Møn. Photo: Kirsten Trampedach, National Museum of Denmark

One way of striving for salvation was to live a pious life, through refraining as far as possible from sin and practising constant penance. Many people did this by taking Jesus as an example and trying to imitate his life. The imitation of Christ (imitatio Christi) had hitherto been reserved for the ascetic cloistered monks, but the practice spread to the lay population in the Late Middle Ages. Whereas people had previously worshipped the victorious Christ, they now cultivated and imitated the suffering and human Christ. At the same time, they began to worship the sinless Virgin Mary more than ever before.

Even those who took Christ and Mary as their role models could not avoid sin, however, so it was important to do penance and promise improvement. Penance could take many forms. One could confess one’s sins to a confessor, and carry out various acts such as lighting candles in church, reciting an appropriate number of Hail Marys, fasting, giving alms to the poor or undertaking a pilgrimage. It was also possible to shorten one’s time in Purgatory through indulgences. The doctrine of the indulgence was that acts of penance could be converted into other pious deeds sanctioned by the Church. Over time, it became possible to buy indulgences for money. The larger the payment, the more days you were spared in Purgatory. In the Late Middle Ages, the importance of indulgences grew significantly, partly because they spread to the entire population, and partly because the pope realised the enormous revenue potential that the sale of indulgences entailed. According to official theology, the indulgence was only effective if the buyer sincerely repented for his or her sins, but this was often forgotten, and the indulgence thus became a commodity.

Saints, donations and religious associations

There were many ways to shorten one’s time in Purgatory; religious practice in the Late Middle Ages was characterised by people ‘doubly insuring’ themselves in order to be on the safe side, as far as this was possible. Should pious living, penance and indulgence fail, one could also ensure that efforts were made for one’s soul after death, for example by asking a saint to intercede with God. The idolisation of saints was largely centred on the worship of relics. The Church of our Lady in Copenhagen held a piece of the cross on which Jesus had been crucified, a scrap of the Virgin Mary’s underskirt and some of the earth from her grave, and a piece of John the Baptist’s head. Many similar relics could also be found in other churches.

Another way to shorten one’s time in Purgatory was to endow a church mass so that one’s soul could be prayed for eternally. Gifts of economic assets, especially incomes from property, to a church or monastery ensured that masses would be held for the souls of the donor and their family, usually once a year on the day of the donor’s death. In the High Middle Ages, donations had primarily been confined to society’s elite, but in the Late Middle Ages, common people joined together in guilds, corporations and brotherhoods that endowed masses for the souls of deceased members. These associations could be based on a common trade or converging religious interests, such as the worship of a particular saint or a way of practising religion. Guilds, corporations and brotherhoods were also social and solidarity associations in which members jointly solved practical problems and assembled in convivial settings. These religious associations brought together high and low, lay and learned, and a large proportion of the members were women.

Towards the Reformation

In summary, it can be said that popular religiosity was far from languishing before the Reformation. On the contrary, there was a democratisation of faith, which became a precondition of the popular Reformation movement that arose in the 1520s. Many of the new religious practices of the Late Middle Ages competed in some sense with the established Church, but, in most cases, the new tendencies were fully reconciled with the traditional forms of religion under the auspices of the Church. However, the religious revival in the Late Middle Ages also created a number of practices that many at the time viewed as speculation and deception – the trade in indulgences and the worship of relics are two of the most prominent examples. The desire for a radical break with the Roman Catholic Church and some of the popular forms of faith constituted a more ‘negative’ precondition for the Reformation.

Humanism and Reform Catholicism

Towards the end of the fifteenth century, Renaissance culture began to spread from the Italian peninsula into western and northern Europe. One of the most important features of this current was Humanism, which put the individual in the centre and used Classical Antiquity as a model for the ideal person and society. Humanism was originally an elitist and intellectual movement; it assumed a particular form in northwestern Europe as so-called Biblical Humanism. The preoccupation with an exemplary past was directed towards the Bible, which was re-translated from the ancient sources and re-studied. Biblical Humanism was strongly critical of Scholasticism, a tradition which, since the High Middle Ages, had combined the Holy Scriptures with Graeco-Roman philosophy in a complex philosophical-religious thought system. The aim of Biblical Humanism was to return to the Bible as a basis for the renewal of religion. Led by the Dutch thinker Erasmus of Rotterdam, the Biblical Humanists strongly criticised the prevailing conditions in the Church and demanded far-reaching reforms.

A prominent Danish representative of this movement was Christiern Pedersen, a canon at the cathedral in Lund. During the years 1508–1515 he lived in Paris, where he published a number of books, including a Latin–Danish dictionary, Peder Laale’s Proverbs (Peder Laales ordsprog), a collection of sermons in Danish and, not least, Saxo’s History of the Danes (Gesta Danorum). With these publications, Pedersen wished to disseminate Humanist and religious knowledge to the wider Danish public. Another representative of the Biblical Humanist movement was the Carmelite monk Poul Helgesen, who became particularly well known for his scathing criticism of misconduct in the Church. Poul Helgesen showed great interest in Martin Luther’s ideas when they circulated in Denmark around 1520, but he maintained a Reform Catholic position and gradually became a staunch opponent of the Protestant movement. Most of the other Humanists, including Christiern Pedersen and several of Poul Helgesen’s pupils, became convinced Lutherans during the 1520s.

Writing, education and books

The Humanists’ wish to raise the level of education in Denmark – through the dissemination of knowledge in Danish instead of Latin, among other things – was an extension of a development that had begun in the late fourteenth century. In the High Middle Ages, learning had been the preserve of a narrow ecclesiastical elite, and Latin had been the dominant written language. An emerging Danish written language had died out in the fourteenth century, most likely because of the collapse of the monarchy. From the end of the fourteenth century, the re-established monarchy and private individuals alike began to write more letters and documents in Danish, and the volume of documents issued increased dramatically over the fifteenth century. One important reason for this was that from around 1400 the expensive parchment on which letters and documents had previously been written was increasingly replaced by paper, which was far cheaper. Written communication was used more and more not only in the royal administration but also in the administration of the Church, rural estates and towns. The nobility began to write private letters with personal content. In the towns, merchants started to make use of accounting books to keep track of their financial activities, and even the peasantry eventually began to keep documents and accounts in small ‘archives’ on their farms.

Throughout the Late Middle Ages, the educational system functioned under the auspices of the Church. Every cathedral had an associated cathedral school, which was supervised by the bishop and the cathedral chapter. Such schools were primarily for the training of parish priests, but some pupils continued their studies at a university. Before the University of Copenhagen was founded in 1479, it was necessary to travel abroad to pursue higher education, which was a requirement for a career in the upper levels of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Many Danes went to study at foreign universities even after 1479, and in the 1520s the University of Copenhagen dwindled away. Local schools had more success and, from around 1400, such schools were established in more and more towns. This success was primarily due to the fact that many burghers sent their children to Latin schools so they could acquire basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic, which they could then use in a secular career, for example as a merchant.

Reading and literacy increased further with the introduction of the printing press in the second half of the fifteenth century. The first books printed on Danish orders by foreign printers were Church works in Latin, but from the final years of the fifteenth century, these works were supplemented with historical works and law books in Danish. The first Danish printing house was also established in Copenhagen at this time. Within a few decades, book production came to include a large number of works on a wide variety of topics. Printing thus made it possible to spread knowledge, news and religious and political views to broad sections of the population.

Cultural imports – Denmark as a German cultural province

Denmark was in constant contact with the outside world. Religious ideas and practices were introduced via the internationally oriented clergy and laypeople on pilgrimages. Travelling merchants and peasants brought home new ways of conducting trade and accountancy. The king imported ideas about state law, coronation rituals, court ceremonies and administrative methods, and the nobility imitated noble identities and lifestyles in Europe. Denmark was on the periphery of Europe’s cultural centres. Many cultural phenomena – from Church art to fashions in clothing and luxury consumption – were inspired from abroad, but also interpreted within the framework of an older Nordic culture.

Inspiration could come from increasingly distant regions, but the largest influence came from the German territories, which is why late medieval Denmark has been pointedly referred to as a German cultural province. Such German influence was expressed not least in the language. Written Danish, as we know it from around 1400, was characterised by many loanwords from Low German, which was an international language across northern Europe. This influence was of lasting importance. Much of contemporary Danish vocabulary – including almost all words with the prefixes an-, be- and und- and the suffixes -hed, -else and -skab – were borrowed from Low German in the Late Middle Ages. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, Dutch culture also increasingly began to influence Danish society.