2. Population and the structure of society

The plague arrived in Europe in 1347. Having raged in Asia for years, it came via the Middle East to the ports of southern Italy and southern France, crossed the Alps to the west and spread through France towards the north. In 1348, it reached England, northern Germany and Norway. The plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, was apparently carried by fleas, which lived on rats and then humans; it is also possible that the infection was spread directly from human to human. The plague may well have reached Denmark in the same or following year, but it was only in 1350 that it broke out in full force. The Skånske Årbog (Skåne Annal) for 1350 stated simply that ‘there was a very large epidemic throughout the year across the world’. Records of requiem masses from the cathedrals in Ribe, Roskilde and Lund testify to a sharp increase in donations received for masses for the dead in 1350.

It is not known exactly how many Danes died of the plague. More accurate source material is available for England, Germany and France, and it has been estimated that around 40–50% of the population in these countries succumbed to the disease. There is no reason to doubt that a similar proportion of the Danish population died in the first wave of the plague in 1350. New plague epidemics in 1360, 1368–1369 and 1379 also killed many people, most likely around 10–15% of the population each time. More epidemics followed later, though these were not as deadly.

Climate change and population decline

The Black Death was not the only disaster to hit Denmark in the fourteenth century. Even before the middle of the century, the effects of the Little Ice Age had begun to take hold in the form of episodic failed harvests and famine. The warm period during the High Middle Ages had contributed to a growth in population, which, combined with society’s highly unequal distribution of resources, meant that parts of the population were living at minimum subsistence level. There is evidence to suggest that the poorest sections of the Danish population succumbed more easily to the plague epidemics because they were already weakened in terms of nutrition and health.

It is uncertain exactly how many people lived in Denmark in the Middle Ages, both before and after the Black Death. It has been estimated that approximately 950,000 people lived in the kingdom immediately before the Black Death, somewhat fewer than in the middle of the thirteenth century. The population fell to approximately 550,000 from 1350 and only really started to grow again in the middle of the fifteenth century, because subsequent plague epidemics checked any emerging population increase. From 1450 to 1500, it is estimated that the population rose to approximately 600,000.

Population decline led to a number of social and economic changes. In the countryside, many farms and villages stood deserted because their inhabitants had died, and land owners had to reduce the peasants’ duties in order to attract labour. Yet those peasants who survived the plague experienced economic progress, since their duties were reduced and more land was available for cultivation. It also became possible for peasants to convert part of their production to livestock, in order to export cattle in particular. The Black Death cost many more lives in the town than in the countryside, but urban population levels recovered more quickly due to migration from rural areas. New export opportunities led to growth in Danish towns throughout the fifteenth century.

The four estates

Let us now look more closely at the various social groups and how they interacted and developed in the Late Middle Ages. We will explore, among other things, the importance of economic and demographic conditions for the different layers of society. Over the course of the Late Middle Ages, Denmark became a society of estates (stændersamfund), the members of which were divided into rather distinct social groups with increasingly well-defined rights and functions. The description of society in this chapter is structured according to the four estates – the nobility (adelen), the clergy (gejstligheden), the burghers (borgerstanden) and the peasants (bondestanden) – and thus follows the ideological categories of the Late Middle Ages. However, as we shall see, the individual estates were themselves relatively diverse, and the boundaries between them were not as clear as the official estate ideology would suggest.

The nobility – position, duties and privileges

The nobility was the dominant social group in late medieval society. They had roots in the aristocracy and herremænd of the High Middle Ages. Their primary function was to defend the realm and the other estates from both internal and external enemies. In return for their loyalty to the Crown and military service, the nobility enjoyed a number of privileges and an elevated status that the other estates did not. Since war horses, equipment and military training were expensive and time-onsuming, the status of professional warrior was reserved for the landowning elite. In the course of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, noble status became hereditary, handed down from parents to children of both sexes. The nobility maintained a strong warrior identity throughout the Late Middle Ages. The word ‘nobility’ (adel) itself was used only from the beginning of the sixteenth century. A common way to refer to the nobility was as ‘honest and well-born men’, which placed noble deeds before birth right. Other terms were ‘knight’ (ridder, miles) and ‘squire’ (væbner, armiger), which underlined the warrior ideal. Any man born into the nobility was a squire and therefore could potentially be knighted. Such an elevation in title often occurred because of valorous deeds on the battlefield or in connection with coronations.

The hereditary nature of the nobility led to a strong family identity, which members demonstrated by wearing ancestral coats of arms. Some members of the nobility also used family names that signalled membership of a specific family (for example, Brok, Hak and Frille), though far from all. Some of the most powerful and self-assured families (for example Gyldenstjerne, Thott and Rosenkrantz) did not. They only began to do this after a royal decree in 1526 demanded that all members of the nobility adopt a fixed family name.

The most important noble privilege was exemption from paying taxes to the king. This applied not only to the nobleman personally but also to his peasant subjects. However, peasants did not benefit from this tax-free privilege, which merely allowed the noble landowners to levy higher duties from them. The birth-given tax exemption was so central to the concept of nobility that noblemen were sometimes referred to as ‘freeborn’. To be free was to be tax-free. Another privilege of the nobility was the right to fine their peasants when they broke the law. This initially only applied to minor penalties but, in the course of the Late Middle Ages, it also came to include the highest sums. The nobility also benefitted from a variety of exceptions from general rules, such as trade restrictions.

Diversity within the nobility

The privileges of the nobility defined them legally and constitutionally as a particular estate demarcated from the others. Unlike in other realms, there was no formal hierarchy within the Danish nobility; all members enjoyed the same rights and were bound by the same duties. In reality, however, the nobility was by no means a homogeneous social group. First and foremost, there were vast differences in the amount of land they owned. The wealthiest noblemen owned hundreds of farms, the poorest only a few – perhaps only the farm on which they lived.

These differences were exacerbated in the Late Middle Ages as a result of the economic crisis among landowners, which was caused by the Black Death. Many lesser nobles found it difficult to maintain their noble status, which required them to perform their military duties and generally lead a lifestyle appropriate to their noble estate. It is not known how large the nobility was before the Black Death, but it is estimated that it was much larger than it was around 1500, the reason being that many of the poorer noblemen were forced to relinquish their noble status and become members of the peasant or burgher estate. Other minor nobles clung on to their status by taking on service positions for high nobles, ecclesiastical institutions or the king.

The middle and higher levels of the nobility were also hit hard by the crisis initially, but those who were able to survive it were ultimately in a position to buy land from lesser nobles who went bankrupt. This was the origin of the very large noble estates that accumulated towards the end of the Middle Ages. In total, the nobility at this point owned approximately 35–40% of the agricultural land in Denmark.

On paper, the nobility was sharply demarcated from the other social estates, but the situation was more nuanced in reality. It was especially difficult to distinguish lesser nobles from well-off peasants and townsmen. There are examples of commoners being elevated to the nobility, either unofficially or officially. In 1475, the nobility was able to push through a provision that a noble woman marrying a man from outside the nobility would lose her noble status, and her landed estate would become taxable. This provision marks the nobility’s wish to remain a closed estate, but it also shows that nobles and non-nobles did actually marry across estate divisions.

Noble Feuds in the Late Middle Ages

Watch this film in which Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm talks about the noble feuds of the Late Middle Ages. The feuds were mini-wars between noble families, with East Jutland witnessing intense conflicts, notably involving the Rosenkrantz, Lange, and Brok families. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about nine minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Noble power and noble feuds

Despite borderline cases and opportunities for social mobility, the nobility in general was a relatively closed estate, and, owing to economic and demographic developments, it became even more closed in the course of the Late Middle Ages. This did not mean that the nobility agreed on everything, however. On the contrary, the Late Middle Ages was characterised by numerous conflicts within the nobility, which at times erupted into open feuds entailing acts of revenge and manslaughter.

The nobility built its power on economic wealth, military strength and social prestige. But noblemen also gained power by holding offices in the royal administration, particularly as royal stewards (lensmænd) at the king’s castles. At the council of the realm, the nobility gained political power and a share in the exercise of government. They could also pursue an ecclesiastical career and take up positions in the highest offices of the church. The influence and wealth that ensued could be used to strengthen their family’s position.

Jens Iversen, bishop of Aarhus, depicted on the altar piece in Aarhus Cathedral (c. 1478-1479). Like most of the late medieval bishops, Jens Iversen was a member of the nobility. His noble lineage is here demonstrated by his family’s coat of arms with three red roses. Jens Iversen defended his own position of power and the independence of the bishop’s seat in a feud against influential members of the noble Rosenkrantz family, who were among Christian I’s favourites. The altar piece was made by the German sculptor and painter Bernt Notke (c. 1440–1509). Photo: Aarhus Cathedral

The clergy as an estate

In the Catholic era, until the Reformation in 1536, the clergy was regarded as the first estate of the realm, since the people of the Church were closest to God. Its function was to communicate the grace of God and proclaim His word to the rest of the population. In return, the other estates had to protect and provide for them. The struggle for the salvation of souls took many forms. Parish priests and mendicant friars spread the Christian faith among the common people through preaching and worship, while cloistered monks devoted their entire lives to praying for society, secluded from its temptations and depravity. In cathedrals, monasteries and parish churches, masses were held for the dead in order to shorten their time in Purgatory. Because churchmen were, in a sense, more holy than ordinary people, they had to live a particularly pure and pious life. This meant, not least, that they should practice celibacy. In reality, however, many clerics lived lives not unlike those of the rest of the population.

The clergy was a very diverse estate. There were vast differences between the social positions and functions of the individual clergy members. This was due to the large, international Church organisation to which the ecclesiastical institutions in Denmark belonged and to which all Danish clergy were subject. The core of the Roman Catholic Church consisted of a hierarchy of clerical offices that ran from the pope at the top down to archbishops and bishops and finally to parish priests at the local level. The Danish ecclesiastical province included the kingdom of Denmark and the duchy of Schleswig, as well as the island of Rügen in northern Germany. Its leader was the archbishop in Lund.

The ecclesiastical province in Denmark was divided into eight dioceses, each led by a bishop. To assist in the administration of the diocese, the bishop had a cathedral chapter consisting of a number of canons, who also elected the bishop. The bishop and the cathedral chapter were located in the town in which the diocesan cathedral stood. At the local level, it was the parish priest who took care of Church activities, conducting baptisms, funerals and marriages, and hearing confession. The parish priests were educated at schools that were connected to the cathedrals. Part of their income came from their own agricultural operations. They were thus involved in the rural community, from which most of them were also recruited.

Alongside this so-called secular clergy was the monastic system, which consisted of a number of international monastic orders. There were land-possessing orders located in the countryside (e.g. the Benedictines and the Cistercians), and there were mendicant orders located in the towns (e.g. the Franciscans and the Dominicans). Most monasteries were founded in the High Middle Ages, but new orders came to Denmark in the Late Middle Ages (e.g. the Bridgettines, the Carmelites and the Order of the Holy Ghost). With their separate international organisation, the monastic orders cut across the secular Church hierarchy, but, to varying degrees, the monasteries were also subordinate to the local bishop. Ultimately, they were all subordinate to the pope.

The clergy’s privileges, wealth and power

The position of the clergy and the ecclesiastical institutions in Danish society was guaranteed through the conferral of extensive royal privileges. Just like the nobility, the clergy were exempt from paying tax and duties, and were entitled to collect fines from their subject peasants. To a certain extent, the clergy also enjoyed legal immunity from the secular judicial system.

The financial basis of the ecclesiastical institutions and offices came from landed estates and income from property in towns. Properties and rents continued to be donated to the church in the Late Middle Ages, but not to the same extent as in the High Middle Ages. Some of the ecclesiastical institutions had very large estates. The bishopric of Roskilde owned approximately 2,500 farmsteads, the cathedral chapter in Lund possessed more than 1,300, and Sorø Abbey had approximately 625. Altogether, the church owned approximately 35% of the country’s land. A major source of income was also the tithe, which had to be paid by everyone. The tithe and duties were often paid in the form of goods (rather than money), which the clergy could sell at market. The clergy were thus not only religious figures but also acted as landowners and merchants.

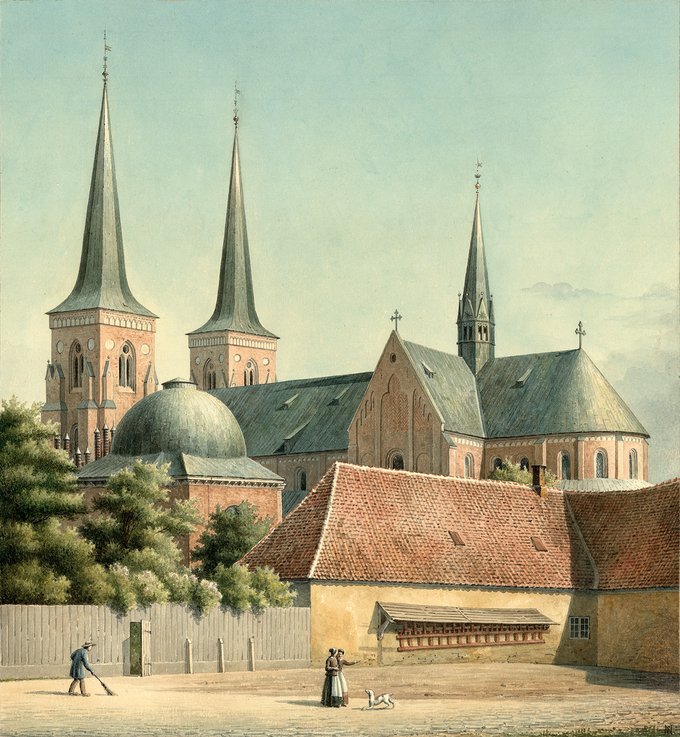

Roskilde Cathedral as it looked in the nineteenth century, depicted as a lithograph. The cathedral was built in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; in the fifteenth century, it was extended with towers, spires and a large burial chapel for Christian I and Queen Dorothea. The Danish cathedrals were centres for the clergy and worship, but also for manifestations of the king’s power. As edifices that towered high above the surrounding houses of the diocese town, the cathedrals demonstrated the greatness of God. Photo: National Museum of Denmark

The position of the Church and clergy as an independent power was weakened during the Late Middle Ages. First and foremost, the Church was undermined by the increasingly strong monarchy. In addition, the inner unity of the Church was divided because the nobility forced itself into high ecclesiastical offices. Many of the bishops in the Late Middle Ages were members of the nobility with limited interest in the pious obligations of the Church. Furthermore, the bishops and the abbots in the largest monasteries were members of the council of the realm, which meant that Church leaders were caught up in the political power struggles of the time. Throughout the Late Middle Ages, however, the ideology of the independence of the Church and the immunity of the clergy was preserved, and the king and the rest of society always had to take this factor into account.

The burgher estate

As a general rule, the burgher estate included all adult men who had acquired citizenship in one of the country’s towns. Each burgher was the head of a household that included both his family and servants. The town was territorially delineated from the surrounding rural community by its own land (bymark), with clear boundaries. It was legally distinguished by virtue of its royal privileges, which officially acknowledged the town as a market town and granted its inhabitants a number of special rights. Each town had its own law (stadsret) and its own court (byting). It also had its own municipal administration, governed by a town council (byråd) consisting of mayors (borgmestre) and councillors (rådmænd) elected by and from among the burghers, together with a royal bailiff (byfoged). This official was eventually referred to everywhere as the town bailiff. In some towns, the burghers had the right to elect the town bailiff themselves; in others, he was appointed by the king or the local royal steward. Town privileges also included exemption from various duties to the Crown, such as customs on trade with other towns.

Growth in the towns

The reason the king gave the towns preferential treatment was that, as trading hubs, they constituted a lucrative object of taxation for him. Around 1350, Denmark had approximately eighty towns. The Danish urban system was characterised by relatively many, yet small, towns. Most villagers had only a short distance to travel to the nearest market town. It was here that they sold their produce and bought goods such as clothes, salt and ironware. Many of these goods were imported from abroad, and others were processed by the town’s craftsmen. This trade created a group of very wealthy merchants, who came to dominate the towns and eventually gained a monopoly in the town council. Craftsmen could not usually accumulate fortunes on the same scale. They organised themselves in craft guilds, which agreed on norms of quality and price, among other things.

The plague epidemics led to a significant reduction in the urban population. A few of Denmark’s small towns (including Herrested and Skibby) were so depopulated by the plague that they lost their market rights and became villages. No new towns were founded between 1350 and 1400, but towns began to grow again from the beginning of the fifteenth century; approximately thirty new towns were founded between 1400 and 1536. Because the population grew faster in the towns than in the countryside, population distribution began to shift from rural to urban areas. Before the plague, approximately 10% of the country’s population lived in towns, but this increased to approximately 14% around 1500. It is therefore possible to speak of relative growth in the towns – and, for some of the larger towns, most likely also absolute growth – during the Late Middle Ages. Overall, the population decline thus led to an urbanisation of Danish society.

An explanation for this surprising development can be found in the re-orientation of exports. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the Skåne fairs lost their significance as diversified goods markets. The herring trade at Falsterbo peaked during this period, but trade in other goods moved to the Danish market towns. Another important factor was the emergence of the lucrative export of cattle to Germany and the Netherlands. This cattle trade took off from the middle of the fifteenth century and particularly benefitted market towns in Jutland and Fyn. These factors led to significant economic growth in the towns.

Urban settlements in Denmark at the end of the Middle Ages. Most of the towns arose during the High Middle Ages (c. 1050–1340), but new towns also emerged in the Late Middle Ages (c. 1340–1523). © danmarkshistorien.dk

Royal trade policy

Other factors in addition to those mentioned above also played a role in the growth of towns in both size and number. The Danish Crown increasingly favoured Danish towns and Danish merchants at the expense of foreign merchants. As the power of the Hanseatic League (a union of trading towns in northern Germany and the Baltic Sea region) gradually declined and the Danish monarchy grew stronger, it became possible for the king to pursue a ‘national’ trade policy, the aim of which – seen from the king’s perspective – was to increase the Crown’s income from trade in Denmark. Increasing the number of towns was part of this policy. A breakthrough for the new Danish trade policy came under Erik of Pomerania, who favoured Danish merchants in various ways. In 1429, he also established the Sound toll (Øresundstolden, a toll on transit through the Øresund), which eventually had a major impact on the Crown’s finances. The Sound toll was introduced in order to compensate for the loss of customs revenue from Dutch and English ships, which sailed through Danish waters (past the Danish king’s toll offices at the Skåne fairs) in large numbers in order to trade directly with towns in the Baltic Sea region.

Another part of the king’s trade policy was to tighten the monopoly of the Danish towns at the expense of the peasantry. It was forbidden to trade directly with peasants in the countryside (landkøb). Instead, the rural population were obliged to sell their produce in the town square of the nearest market town. It was also forbidden for peasants to sail to northern Germany and sell their produce there, a trade which was practised especially by peasants from the southern Danish islands.

Efforts to channel trade through the Danish market towns and prevent direct trade with peasants intensified from the middle of the fifteenth century. However, the trading activities of the nobility and the clergy – as well as the peasants’ voyages to Germany – continued, which created discontent among the burghers.

Rich and poor in the towns

Economic growth in the Danish towns led to the emergence of an urban elite which possessed great wealth and influence at the local level. In the second half of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century, some of the most prominent burghers were even involved in royal administration. This was to the great annoyance of the nobility, who believed they had an exclusive right to royal offices. Generally speaking, the burgher estate was a natural ally for the king in his attempt to balance the power of the nobility. The growing animosity between the nobility and the burghers led to a series of conflicts in the Late Middle Ages, and erupted during the Reformation period.

The Crown’s town policy also meant that the divisions between the estates became clearer. In step with the drive to concentrate trade and artisan production in the towns, the boundaries between urban and rural occupations, and thus between those living in the towns and in the countryside, became even sharper than before. Within the towns themselves, economic and social development led to increased social disparities. As the wealthy merchants grew richer and more powerful, animosity between them and the urban middle class of craftsmen and smaller traders grew. In some towns, this led to open conflicts between the town council and the merchant elite on the one hand and the ‘common people’ on the other, who criticised the town council’s privileges and demanded the right to participate in urban government.

In addition, an underclass of poor and destitute people gradually emerged, who often had to support themselves by begging. In a time when labour shortages could still occur, begging was increasingly viewed as an unacceptable expression of laziness. The view of poverty thus changed during the Late Middle Ages as people began to distinguish between the ‘honest’ poor, who were unable to support themselves and should thus be helped, and the ‘dishonest’ poor, who were able to work and therefore undeserving of relief.

The peasant estate

Despite a certain degree of urbanisation during the Late Middle Ages, the vast majority of Denmark’s population still lived in the countryside. Only a vanishingly small proportion of those who lived in the countryside, however, were members of the nobility or clergy. The majority belonged to the peasant estate, which included landowning farmers, tenant farmers, cottars, rural artisans, millers and, under them all, the people who lived in their households as servants.

The decline in the population led to extensive changes in the rural community. The tenants who survived the plague epidemics had their annual land rent cut by approximately 50%. At the same time, the landowners had to reshape the farming system itself. Before 1350, a significant proportion of Danish agricultural land had been farmed by large-scale operations centred around so-called ‘bailiff farms’ (brydegårde) with associated smallholdings inhabited by tenant peasants and cottars, who supplied labour to the bailiff farms. After the plague epidemics, this system could no longer be sustained because so many of the tenants and cottars had died. The landowners had to close down the bailiff farms and the smallholdings and distribute the land evenly between the remaining peasants. The new holdings were, on average, significantly larger and could, in contrast to the earlier smallholdings, provide a livelihood for a nuclear family with servants. The population decline in the Late Middle Ages thus created the Danish family farm, which remained the backbone of the country’s agriculture for centuries.

The system of bailiff farms had by no means been all-encompassing. Alongside it, there had always been many viable family farms. But for those peasants who went from being inhabitants of smallholdings to being tenants of larger, self-sustaining family farms, population decline represented a major economic improvement. The time they had once spent working at the bailiff farm could now be spent on their own farm, their duties were reduced and they had access to more land. In addition, the peasants could now use land that had previously been under the plough to graze their livestock. This enabled them to meet the rising international demand for cattle from the middle of the fifteenth century. The peasants thus came into contact with the market and were further integrated into the monetary economy. They were now in a position to purchase imported goods such as cloth and spices.

The Black Death

In this film, Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm discusses the plague, also known as the Black Death, which reached Denmark in 1350. The Black Death caused significant changes in both the economic, political, and religious life of the Late Middle Ages. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about 11 minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Tenant peasants and landowning peasants

Most peasants were tenants under the Crown, the nobility and ecclesiastical institutions. Landowning peasants constituted only a small part of the peasant estate (they owned approximately 15% of the farmsteads); the rest were tenants who leased their copyholds from a lord. The tenant peasant was under the protection of his lord, which meant the lord had to defend him legally and physically from infractions. In return for this protection and the use of the farm, the tenant peasant paid duties to the lord, which included land rent (landgilden) and so-called ‘lordly duties’ (herlighedsafgifter). Most of the ecclesiastical institutions had long been able to impose criminal fines on their tenants, and, gradually, landowners from the nobility were awarded similar privileges. These conditions meant that tenant peasants were kept in a dependent position under their lords. Landowning peasants were no freer than tenant peasants since, from the fourteenth century, they were regarded as belonging to the Crown. Instead of paying rent to a lord, they paid tax to the king. In social and economic terms, there was thus little difference between the landowning and the tenant peasants.

In less fertile areas such as western Jutland or eastern Skåne, a substantial number of peasants lived on isolated farms, but most peasants lived their lives in villages. Here they were part of a village community, the purpose of which was to ensure a fair distribution of village resources and joint solutions to practical problems such as arable farming, hedging and grazing. To a large extent, these matters and the conflicts they could give rise to were left to the peasants themselves, with no involvement from the estate owners or the judiciary.

Peasants and estate owners

Despite some remaining internal differences within the peasantry, population decline and the estate owners’ crisis led to the emergence of a more homogeneous and self-assured peasant estate. As the population grew throughout the fifteenth century, however, the supply and demand relationship between land and labour changed once again in favour of the estate owners. The new, very low land rent was deemed unchangeable, so landowners instead raised the so-called herlighedsafgifter, the lordly duties (including fees for protection). In the 1490s, lords in Sjælland introduced vornedskab (villeinage), which bound tenant peasants to the farm on which they were born. The aim of villeinage was to prevent peasants moving if they were offered better conditions at a neighbouring estate. From around 1400, landowning peasants across the kingdom were instructed to keep their land under cultivation. If their heirs refused to take over the farm, they could be forced to do so. The king also increasingly levied extraordinary taxes from the peasant population. Such demands created discontent among the peasantry, who had quickly become accustomed to low duties and freer conditions, and who were now in a position to assert themselves collectively. The result was extensive peasant uprisings in 1438–1441, in 1472 and during the Reformation period in the 1500s. Although all the uprisings were brutally suppressed, they marked the peasantry as a political player that could not be ignored.