1. Denmark in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages is often described as a time of decline – a period characterised by decay and crisis. The Black Death, the Little Ice Age, the Hundred Years’ War and chaotic conditions in the Catholic Church are examples of crises that are often highlighted at the European level. It is certainly true that the Late Middle Ages witnessed its fair share of disasters and upheavals. However, it is not accurate to describe the period as one of general decline. Epidemics of plague and failed harvests cost many lives, but also initiated social and economic changes that ultimately led to growth and renewal. The wars of the period were brutal and bloody but they were also an expression of the growing power of kings and princes, foreshadowing the modern state. The tumultuous conditions in the Roman Catholic Church, with as many as three contenders for the papacy at one point during the Papal Schism of 1378–1417, were connected to the growing power of secular rulers and also led to Church reforms in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Despite power struggles at the top of the Church hierarchy, religiosity among the general population flourished, a development which has been referred to as a ‘democratisation’ of faith. Alongside these changes, Renaissance culture spread from northern Italy across the whole of Europe.

Rather than as a period of decline, therefore, the Late Middle Ages should be seen as an era characterised by colossal changes. This can be said of all periods in history of course, but many historians believe that the development of society during the Late Middle Ages – with its unique mix of crises, disasters, renewal and growth – was a precondition for the significant leap forward towards a more modern society that occurred from around 1500.

Denmark was a part of this European and, in some respects, global development. The plague and the Little Ice Age affected Denmark as well as the rest of Europe. In Denmark, as in many other places in Europe, the power of the monarchy increased dramatically at the expense of that of the Church, and, towards the end of the Late Middle Ages, Renaissance culture reached the northern latitudes. Like other European kingdoms, Denmark took part in a number of wars that made their mark on the development of society.

Realms and territories ruled by the Danish Crown

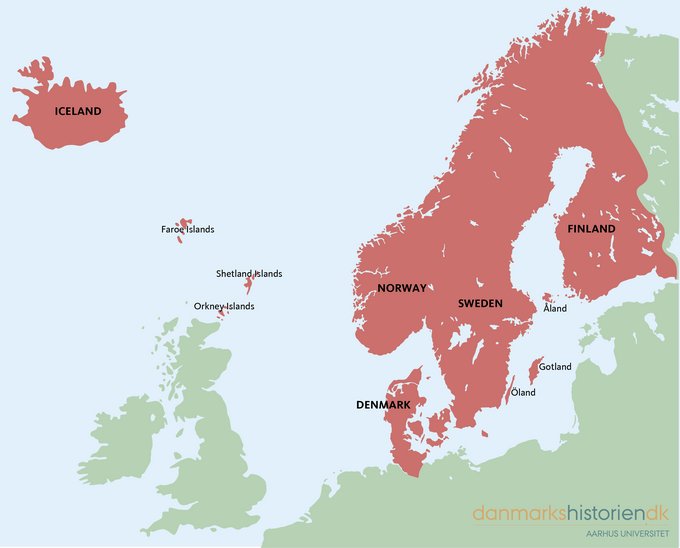

What was the ‘Denmark’ that went through all these changes? As shown in Chapter 2, the Denmark of the Middle Ages was much larger than it is today. During the Late Middle Ages, a number of significant territorial changes took place. In 1340, after the interregnum of 1332–1340, the Danish king was not even master in his own house, as most of the kingdom was mortgaged to the counts of Holstein. The Danish kingdom was re-established within a relatively short space of time, however, and in 1361 Denmark gained the island of Gotland from Sweden. In 1346, Estonia was sold to the Teutonic Order in order to raise money to redeem the Crown’s mortgaged territories. Towards the end of the fourteenth century, Denmark became the dominant party in the Kalmar Union, which meant that the king of Denmark was also the ruler of Norway (including Iceland and other dependencies) and Sweden (including Finland). In practice, however, the Danish king ruled Sweden only periodically, just as his control over Norway was at times uncertain or entirely absent. Sweden left the union completely in 1523. At the beginning of the Late Middle Ages, the duchy of Schleswig was as good as lost to the Danish Crown, but King Christian I became the ruler of Schleswig and the county of Holstein in 1460.

The Denmark of the Late Middle Ages was not only territorially different from the Denmark of the 2020s, but also much more loosely integrated. Unlike the modern, sovereign nation state, the Danish realm in the Late Middle Ages was held together solely by the regent, who held different positions in the different parts of the realm. The core was made up of the kingdom of Denmark, which consisted of Jutland (including Fyn), Sjælland and Skåne. From 1460, the king was also duke of Schleswig and count (from 1474, duke) of Holstein. Schleswig was a fief under the Danish Crown, so here the king was his own vassal. It remained a Danish royal fief after it was divided between Christian I’s sons, King Hans and Duke Frederik, in 1490, but the king exercised only very indirect royal power in Duke Frederik’s part. Holstein was a fief under the German-Roman emperor and was joined to the rest of the Danish realm only because the Schleswig-Holstein Knighthood wished to maintain the link between the two duchies; they made the Danish king the duke of Holstein, and thus the emperor’s vassal in this region.

In the era of the Kalmar Union, the Danish king was also king of Norway and Sweden, but this was a personal union in which the three realms were in principle independent of each other, and only bound together by the king himself. The king was therefore the ruler of the three realms on different terms. Denmark and Sweden were elective monarchies while Norway was a hereditary monarchy, and the three kingdoms each had their own laws, traditions and political institutions that the king had to respect. In all three kingdoms, the king shared power with a rigsråd (council of the realm) dominated by the nobility, which increasingly demanded influence over the exercise of government. From the middle of the fifteenth century, Sweden was governed for long periods by the Swedish council of the realm headed by a Swedish rigsforstander (viceroy). The Norwegian council stood in a weaker position to the king, since the Norwegian nobility had less economic power than the Swedish, and Danish noblemen were given seats on the Norwegian council.

The Kalmar Union 1397–1523. The most important feature of the union was that the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden shared one king. The union was formally established in 1397 when Erik of Pomerania was crowned king of all three kingdoms in the Swedish town of Kalmar. The Kalmar Union had its centre of power in Denmark, but all the kingdoms were mainly governed by their own established laws and traditions. © danmarkshistorien.dk