3. The monarchy

The king’s tasks were to maintain peace and justice internally and to defend the realm from external enemies. In return, the population had to pay taxes and show loyalty to the king. Throughout the Late Middle Ages, the king generally gained more power over society and was able to extract more resources from it. Governance also became more institutionalised, anticipating the development of the modern state.

Expansion of the power of the Crown

If a ‘state’ is defined as an organisation that effectively exercises a monopoly of power within a given territory, then it is not possible to speak of a Danish state in the Middle Ages. Denmark’s borders were more or less fixed, but the king and his officers had no monopoly on the exercise of power, either formally or in practice. In the Late Middle Ages, however, the Crown was evolving towards what became the Early Modern state, which arose after the end of the civil war known as the Count’s Feud (Grevens Fejde) in 1534–1536. While no actual state had yet come into being, it is therefore possible to speak of state formation in the Late Middle Ages. This development was not smooth and effortless – it was not a gradual, evolutionary process. The Crown’s centralisation efforts sometimes faced fierce resistance from various social groups, not least the nobility.

Between 1340 and 1523, the Danish monarchy was strengthened both externally and internally. In relation to the outside world, Denmark went from being a mortgaged kingdom at the mercy of foreign rulers to being a regional great power. This transition will be discussed in the next section. The present section, however, concentrates on the growth of the monarchy within Danish society. External and internal developments were of course connected, but only partially. Territorial expansion did not necessarily lead to a stronger monarchy internally, just as the relinquishment of land or military defeats did not necessarily weaken the king’s dominion over the Danish population. However, seen over the entire period, Denmark’s stronger position in relation to its neighbours corresponded to the increased power of the monarchy internally.

The Danish Realm and the Kalmar Union

In this film, Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm discusses a series of key points in the political development of the Danish realm: From the majority of the realm being mortgaged, to the Kalmar Union, and onwards to the Stockholm Bloodbath in 1520. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Reasons for the growth of the monarchy

The underlying reasons why the monarchy could expand its influence over Danish society in the Late Middle Ages are to be found in the economic and social changes described above, as well as in military innovations. The population crisis after the plague epidemics generally weakened the nobility and the Church, which made it possible for the king to strengthen his position at their expense. Crown lands had been affected by the decline in land rents and the problem of deserted farms in the same way as the nobility and the Church. Yet the crisis hit the smaller landowners the hardest; the larger landowners fared better, and the king was the largest single landowner of all, since the Crown’s estates, which had grown since the High Middle Ages, amounted to approximately 10–12% of the farmsteads, not counting those of the landowning peasants. Tariffs and duties on the growing trade made it possible for the king to compensate for the loss of income from the Crown estate, improving his economic position relative to that of the nobility and Church, as these landowners did not have equivalent options. Social development and the consequent strengthening of the burgher and peasant estates meant that the king could increasingly align himself with these groups against the nobility.

Advances in military technology and tactics, which took place in many parts of Europe in the Late Middle Ages, were also of great importance. Gunpowder and the increased use of infantry meant that the heavy, lance-wielding cavalry became less dominant on the battlefield, which gradually undermined the military importance of the nobility. This was a protracted development that only reached its culmination in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but it was already well underway in the Late Middle Ages. The many wars of the period demanded a large infantry (especially foreign mercenaries), new fortifications to withstand cannon balls and better warships. Investments in the military were so large that they could only be financed by a central organisation, and the monarchy was the only option. Since the king could not raise sufficient funds from the Crown’s own assets (such as the Crown’s estate or the tariffs it could levy), he had to finance the military by imposing taxes on the commoners (the burghers and the peasants). This challenged the framework of the ‘feudal’ society, since the nobility’s and the Church’s peasants were exempt from paying ordinary taxes. For this reason, taxes had to be granted by the council of the realm each time, as extraordinary taxes (landehjælp). Such extraordinary taxes were levied more frequently from the middle of the fifteenth century. At the same time, during some of the wars, there was significant military conscription of commoners, which also marked a new development. Overall, therefore, military developments led to a tendency for military power and resources to be concentrated around the king.

The monarchy and the nobility

The relationship between the monarchy and the nobility alternated between collaboration and conflict. It was in the interests of both parties that peasants and burghers paid their dues and that the commoners did not revolt. The king and the nobility held together to protect the Christian faith and the Church, which functioned as the ideological foundation for social order. They also usually worked together to protect the realm from external enemies. But, at the same time, the king and the nobility had conflicting interests in many areas. These often centred around the king’s right to extract resources from the nobility’s and the Church’s tenant peasants, and the nobility’s right to influence the exercise of government. The king sought to demand taxes, duties, labour and military service from the peasants holding land from the nobility and the Church, while these landowners wished to maximise their own exploitation of the peasantry. Even during periods of peace and unity, a continuous tug-of-war over the distribution of power and resources was taking place beneath the surface.

The nobility had an ambivalent attitude towards the growth of the monarchy. On the one hand, they perceived centralisation as a threat to their inherited privileges, power and wealth. Yet, on the other hand, the early development of the state brought a number of advantages for a nobleman who enjoyed the king’s favour. The term ‘monarchy’ (kongemagten) refers here not only to the king himself but also to the inner circle of loyal people surrounding him, including members of the nobility. Such men were granted court offices, seats in the council of the realm, administrative districts (len) and special privileges in return for their support of the king. But even for those noblemen who did not belong to the king’s inner circle, the growth of the monarchy could bring benefits in the form of len and offices. The king had to navigate continually between the various groups within the nobility and accommodate more autonomous noblemen in order to avoid dissatisfaction or rebellion.

Since the thirteenth century, the nobility had demonstrated its political power over the king through the assembly of the Danehof (the ‘court of the Danes’). In the second half of the fourteenth century, the Danehof was gradually replaced by the rigsråd (the council of the realm), which was a narrower but more stable body. The king appointed the council’s members, most often from the higher strata of the nobility. All the bishops as well as abbots from some of the larger abbeys had permanent seats in the rigsråd, which was formally led by the archbishop.

On special occasions, the king could summon the entire nobility to a ‘general meeting of lords’ (herredag). The idea developed within the nobility that the king should rule together with the council of the realm, on the basis of an array of constitutional guarantees for the nobility and the Church. Drawing on medieval political philosophy, historians have termed this aristocratic-constitutional ideology regimen politicum. The opposite of this was regimen regale, which was asserted by the king and his most loyal people. This latter, more monarchic, form of governance gave the king freer rein in the exercise of government and afforded fewer guarantees to the nobility.

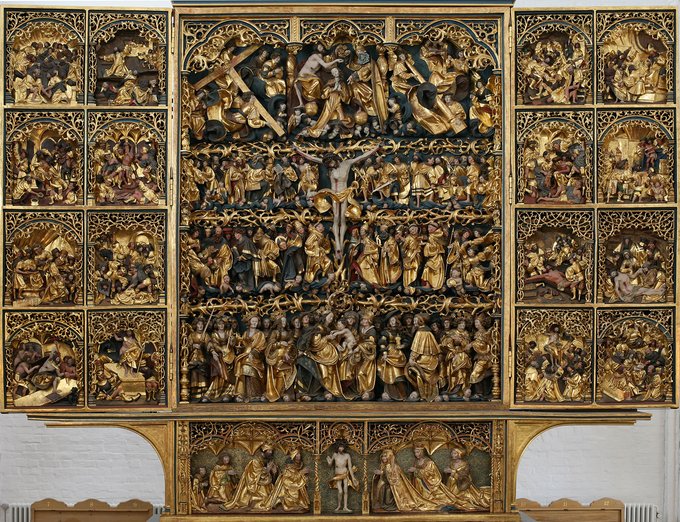

The altar piece in Odense Cathedral, made by the German sculptor Claus Berg (c. 1475–1532), c. 1514–1523. In the lowest panel are King Hans, Queen Christine, Christian II and several members of the royal family. The altar piece was originally housed in the burial vault in the Franciscan monastery church, Gråbrødrekirken, in Odense; it is a good example of the monarchy’s use of the Church for the staging of power. Photo: St Knud’s Cathedral, Odense

Coronation charters and noble rebellions

Political development in the Late Middle Ages can be seen as a constant struggle between regimen regale and regimen politicum. For proponents of the constitutional standpoint, regimen politicum, the most important weapon was the right to elect the king. Denmark had long been an elective monarchy, where the title of king was not automatically handed down to the deceased king’s closest descendant but where the new king was elected – in principle by all the estates, in practice by the nobility. The king often ensured that his eldest son would be proclaimed as heir to the throne, so that in reality, the crown was inherited, and the nobility accepted this for the sake of stability and continuity. But the royal heir still had to be elected to the throne following the previous king’s death, and the nobility could exploit this to demand concessions and guarantees from the king. This found expression in the writing of a coronation charter (håndfæstning), which the future king had to sign and in which he promised, among other things, to follow the advice and recommendations of the council of the realm, to protect the Holy Church and to respect the rights and privileges of the estates. The purpose of these coronation charters was to limit royal power and to guarantee the influence of the nobility and the bishops through the council of the realm. In practice, every king violated the terms of his coronation charter to a greater or lesser extent. On the basis of increasingly extensive and rigorous coronation charters, it has been assumed that the king became weaker and the nobility grew stronger from the second half of the fifteenth century. In reality, almost the opposite is true. The stricter charters signify a counter-reaction to the growing strength of the monarchy.

For long periods, the relationship between the king and the nobility was characterised by collaboration on common goals, but there were limits to what even the most loyal of noblemen could accept. Discontent with monarchic politics led to a number of armed uprisings of nobles. In Jutland, noblemen rebelled against Valdemar Atterdag as many as three times, but the king managed to repress them each time. This was not the case for Erik of Pomerania, who was deposed and replaced with Christopher of Bavaria in 1439–1440. Christian I succeeded in defeating a noble rebellion in 1466–1469, but in 1523 Christian II was forced into exile after the nobility had renounced their fealty, denounced him as an enemy and summoned his uncle, Duke Frederik (Frederik I), to the throne. The right of the nobility to rebel against the Danish king if he did not adhere to the council’s terms in his håndfæstning was written into the coronation charters from 1483. State formation continued despite these rebellions, because even advocates of regimen politicum benefitted from a relatively strong central power, as long as it was subject to the dominance of the nobility. Yet the threat of uprisings marked the limits of the potential for growth in the power of the Crown in the Late Middle Ages.

The monarchy and the Church

Under the leadership of powerful archbishops the Danish church had opposed the monarchy for a period in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, but by the middle of the fourteenth century the time of the great conflicts between king and Church was over. The new power relations between the two were demonstrated when Archbishop Jacob Kyrning died in 1361. The right to freely elect the archbishop belonged to the cathedral chapter in Lund, but Valdemar Atterdag presented himself personally in the town and put pressure on the canons to elect his own candidate, the Roskilde canon Niels Jonsen, who had previously been Valdemar Atterdag’s private chaplain. This event was characteristic of the relationship between the monarchy and the Church in the Late Middle Ages. The monarchy could exert increasing influence on the Church through the distribution of ecclesiastical offices. The king’s desire to dominate the Church was neither strange nor new, but there were several reasons why it became possible to realise it at that point in time. The primary reason was the growth of the Danish monarchy as a result of economic and military changes – that is, the same factors that strengthened the king in relation to the nobility. Another reason was the crisis in the Roman Catholic Church, which weakened the Church in relation to secular princes across Europe.

For most of the fourteenth century, the papacy was relocated to Avignon in France (1309–1377), following which, there was a period with several rival popes (1378–1417). These chaotic conditions weakened papal power and undermined confidence in the Church right down to the local level. In order to reconcile differences, a number of reform councils were convened in the first half of the fifteenth century, intended partly to resolve the papal schism and partly to reform the Church in its entirety. Denmark supported the reform councils in so far as they were politically beneficial to the monarchy, but, towards the middle of the fifteenth century, the reform councils collapsed. The papacy was reestablished in Rome and formed an alliance with Europe’s secular princes at the expense of local ecclesiastical institutions. In return for the princes’ recognition of the pope and his right to levy heavy taxes on the clergy, the pope allowed the princes to control the clergy and ecclesiastical institutions within their own territories. It was significant for this development that in 1474 Christian I was granted a papal privilege to appoint the two highest offices in each of the Danish cathedral chapters.

Towards the national Church

The influence of the monarchy on the Church was also manifested in other ways. The king secured the loyalty of a number of clergy by employing them in the royal administration and paying them with income from ecclesiastical offices, such as the canon offices in the cathedral chapters. The king also exercised increasing influence over the monasteries by taking charge of the continued reforms in the monastic system. There were thus strong indications that the Danish Church was evolving into a national Church, but for several reasons this development did not reach fruition in the Late Middle Ages. The most important of these was the continued influence of the papacy. As long as the Danish Church was subject to the Roman Catholic Church and its international hierarchy of ecclesiastical institutions, offices and courts, the local clergy were guaranteed a certain degree of protection. Another important factor was that not only the king but also the nobility exerted their influence on the Church. Several bishops and high priests were noble by birth and used their ecclesiastical positions to strengthen their own family and allies – and occasionally to oppose the king. It was only with the Reformation in 1536 that the king could finally break the connection to Rome and shatter the nobility’s power over the Church.

The royal administration

Throughout the entire Late Middle Ages, the backbone of the royal administration consisted of castles, each with their associated len (administrative district). In each castle, there was a royal steward (lensmand), who was both a military commander and administrative leader of the area. In addition to providing cavalry for the king’s wars, the steward managed the Crown’s lands within the len, provided legal protection for the king’s tenant and landowning peasants, collected duties imposed on the entire population of the district and oversaw the administration of justice. The len consisted of one or more rural districts (herred; plural herreder – compare the English hundred), which were legal and administrative districts. The functions here were handled by the herredsfoged, the rural bailiff, who was appointed by the royal steward from among the peasantry. The steward himself was almost always a member of the nobility. He was the king’s official and could in principle be dismissed at the king’s pleasure.

The approximately forty castles and associated len could be given to the royal stewards (lensmænd) on different terms. In the so-called ‘account districts’ (regnskabslen), the steward had to submit annual accounts for revenues and expenses. Any surplus had to be paid to the king’s chamber, ‘the pantry’, while the royal steward received a fixed salary or a share of the surplus. The so-called ‘fee districts’ (afgiftslen) were subject to a fixed annual fee payable to the king. The royal steward did not receive a salary but collected any remaining surplus once the fee had been paid. In case of a deficit, the steward bore the loss. Len could also be given ‘for service’; here, the royal steward collected all the profits and his only obligation was military and court service. Service districts or ‘free districts’ (frie len), as they were also called, were given as special rewards or to buy political support for the king. Len could also be used as security for the nobility’s loans to the king. The royal steward in these so-called ‘pledge districts’ (pantelen) received all the income of the len until the king had repaid the loan. He could only be dismissed once the king had cleared the debt, or if he committed serious crimes against the king or the inhabitants of the len.

Royal len were coveted because they provided the royal steward with a large income as well as military and legal power. Wealthy nobles could combine the possession of royal len with private estates and build up significant power bases. This entailed a risk for the monarchy, who preferred to appoint royal stewards of lower social status on conditions that were favourable to the king (‘account districts’ or ‘fee districts’). However, the king was both politically and financially dependent on the upper nobility and was therefore often forced to give len to powerful noblemen. The largest landowners and members of the council of the realm were almost entitled to a royal administrative district, and the king often needed to mortgage them to raise money to finance wars and court ceremonies.

Competition for control of len

There was a constant struggle over the distribution of the administrative districts – the len – between the king and the nobility, and between various groups within the nobility. To a certain extent, shifting power relations between the king and the nobility throughout the Late Middle Ages can therefore be reconstructed by following the allocation of len. During Valdemar Atterdag’s reign and the first long phase of Margaret I’s reign (i.e. the second half of the fourteenth century), many of the len were given to powerful Danish and German nobles in return for their support in rebuilding the Danish kingdom following Holstein rule. From around 1395, Margaret tightened her grip on the len system by redeeming the mortgaged len, demanding correct financial accounting and appointing more faithful royal stewards. This policy continued under Erik of Pomerania, who increasingly employed royal stewards of a lower social status, as they were easier to control. Dissatisfaction with this policy was one of the reasons Erik of Pomerania was removed from power. During the reign of his successor Christopher of Bavaria, a few families of the upper nobility dominated the royal len. This continued under Christian I, who financed his wars and territorial expansions by mortgaging a growing number of districts to the wealthy Danish nobility. After winning a confrontation with a group of such noblemen (1466–1469), and with a gradual improvement in royal finances, Christian I began to redeem the mortgaged len and appoint royal stewards of a lower social status. This policy was continued by King Hans, who even employed royal stewards who were not members of the nobility. Christian II continued, undeterred, to use non-noble royal stewards and generally strengthened his control of the len system, which ultimately contributed to the noble rebellion against him in 1523.

The struggle over the distribution of len was not a zero-sum game in which the king’s power rose and fell without ultimate gain. The state formation process continued alongside all the disagreements about the allocation of len, even in periods when the len system was dominated by the upper nobility. The nobility’s interest in monopolising governance of the administrative districts was precisely due to the fact that the monarchy was able to extract ever greater resources from the population via the len. Therefore, even the most unruly nobleman acted as ‘monarchically’ within his own len as the king’s most loyal officers did in theirs. Mortgaged len have been presented as something entirely negative for the monarchy, but such districts were necessary to finance its growth and, from the point of view of the nobility, loans to the king against security in len were regarded as investments in state formation.

The management of the chancery

The continued growth of the monarchy was also reflected at the central level. During the Late Middle Ages, the central administration was expanded to deal with increasing royal revenues and to accommodate the desire to keep more accurate accounts of the Crown’s finances. The chancery became the most important body in the central administration. Its staff consisted predominantly of clergymen, some of whom were non-nobles, and the chancellor was always a member of the clergy. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, the chancery tightened the auditing of the royal stewards’ accounts, indicated by the preservation of such accounts from the 1480s onwards. From the 1520s, overviews of the Crown’s total revenues across the whole of Denmark are extant. The chancery was also responsible for preparing the increasing number of kongebreve (royal decrees, which constituted a large part of the administrative practice). The development of the central administration towards the end of the Middle Ages was thus characterised by an increase in the number of administrative tasks and staff, the greater use of administrators of lower social status and better control of the len system.

Legislation and the judiciary

The king’s duties included, among other things, maintaining the peace, protecting the weak and ‘enforcing law and order for everyone’. The notion of the king as a guardian of peace went back a long way, and, in the Late Middle Ages, it continued to constitute a large part of the legitimacy of the kingdom. As a Christian prince, the king had to help the good and punish the evil; his most important tools for this were legis-lation and the judiciary. The kingdom of Denmark was divided into three provinces: Jutland (including Fyn), Sjælland and Skåne. Each of these provinces had its own laws. These provincial laws had been written down in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and were in force throughout the whole of the Late Middle Ages and afterwards.

Towns had their own special laws, the so-called town laws (stadsretter). Moreover, the monarchy increasingly legislated for the entire kingdom. Each province had its own provincial assembly (landsting), which dealt with specific cases and functioned as an appeal court for the lower courts. Under the provincial level, there were different types of lower court. In rural areas, each of the small districts, the herreder, had its own court or assembly (herredsting) under the direction of the herredsfoged (bailiff), who was appointed by the royal steward. In the towns, the town court (byting) remained the only court for a long time, but during the fifteenth century another one emerged: the town council court (rådstueret). In this court, the town councillors acted as judges. The highest court in the kingdom was the king’s court of final appeal (Kongens Retterting), where the king acted as judge alongside the council of the realm and other nobles. Cases could be appealed from lower to higher courts, but there was no fixed hierarchy of appeals.

The king’s law

The monarchy’s endeavour to gain control of the judiciary was a long and arduous battle that was still ongoing at the end of the Middle Ages. The main problem was that the king did not have the necessary means to enforce the law; there was no police force and there were no prisons. It was largely left up to conflicting parties to take the law into their own hands, and vigilantism was thus recognised by law to a certain extent. For the same reasons, the local courts (ting) retained some aspects of their original function as public assemblies, which people used voluntarily to settle conflicts. The rural courts (herredsting) and provincial assemblies (landsting) only gradually developed into law courts as we know them today. Many breaches of the law were settled privately without any involvement of the courts. The prevailing sanction was compensation (to the victims), rather than punishment. For particularly serious crimes, the perpetrator could be outlawed, after which anyone could kill him with impunity.

These conditions favoured the stronger members of society, leaving the weak to seek protection from strong patrons. From around 1300 at the latest, every tenant peasant was under the protection of his lord, and every landowning peasant was under the protection of the Crown. Since the Church and the nobility also had the right to fine their peasants, the manorial lords generally played a major role in the administration of justice and conflict resolution in the Late Middle Ages. This ensured a certain legal order but also provided ample opportunities for noblemen to abuse their power. The monarchy’s attempt to gain more influence over the rule of law took the form of increased control of the courts. The king’s court of final appeal (Kongens Retterting) became key to this attempt, partly because it provided an opportunity for the general population to appeal unfair verdicts and partly as a tool for the advancement of the king’s own interests. The stricter supervision of the len system, including the rural bailiffs, must have also made the rural assemblies (herredstingene) less dependent on local potentates, but abuse and violations occurred throughout the entire period.

Church law

Alongside the secular legal system, the Church had its own legal system in which people were judged according to the internationally valid Canon Law, and cases from the ecclesiastical courts in Denmark could be appealed to the papal court. The ecclesiastical legal system took care of cases in which one or both parties belonged to the clergy. It also covered certain types of crime, regardless of whether the parties involved were clergy members. These so-called spiritual (åndelige) cases included matters such as blasphemy and sacrilege, but also marriage, extra-marital sex (which was illegal), money-lending and wills. In addition, crimes that fell under secular law could also trigger a Church sanction, since the crime was not only a violation of the victim and the peace but also a sin against God. For example, the secular punishment for manslaughter usually meant that the transgressor was outlawed, or required to pay compensation to the victim’s family and a fine to the king. On top of this, the Church would impose penances such as fasting, pilgrimage, giving alms to the poor or paying a fine to the Church. For crimes that were publicly known, the culprit also had to confess his sins to the entire church congregation. The most severe ecclesiastical punishment was excommunication, which meant the criminal was excluded from the church community. Canon Law was administered by the bishops and cathedral chapters, who delegated the judging of a number of minor offences to their bailiffs and officials.

The boundaries between secular and ecclesiastical jurisdiction were unclear, and, in reality, the different courts ‘competed’ with each other. Over time, people became dissatisfied with the Church’s involvement; for example, in 1477 the inhabitants of the island of Langeland declared that they would no longer sue each other in the Church courts. The monarchy also worked to limit the jurisdiction of the papacy, and, in 1449, managed to arrange that Danish legal cases could not be taken to the papal court unless they had first been tried in a Danish court. The papal high court and the local ecclesiastical courts only lost their significance during the Reformation period, however.