5. Foreign policy: from the Cold War to the new European and global (dis)order

Danish foreign policy challenges have changed considerably since the early 1970s. This is particularly due to decisive shifts in the international order that occurred during the transition from the bipolar Cold War to a more multipolar world order, with the USA as a dominant power. The dynamics of European integration are another major cause, especially concerning the transition from the EC to the EU. At times, foreign policy was strongly polarised, such as during the footnote period in the 1980s, in 2003 when the decision was made to enter the Iraq War and in European policy throughout the entire period.

Danish foreign policy shifted during the period, from an active internationalist commitment to creating and supporting a rights-based international peace framework, based on the UN, to military activism dominated by the desire to remain close to the USA. Since 2015, Denmark has maintained a precarious balance between something that resembles a more inward-looking strategy on the one hand, and attempts to rethink Denmark’s international commitment on the other, in light of the many uncertainties created by the fallout from – among other things – the UK’s withdrawal from the EU (Brexit), and more unilateral and assertive policies pursued under President Trump in America and President Putin in Russia. The Ukraine War in 2022 has strengthened this development considerably.

Between Cold War détente and conflict

The Cold War détente, which had begun in the 1960s, reached its peak in the 1970s with the signing of the Helsinki Final Act in 1975. This declaration paved the way for dialogue and increased interaction between East and West. Denmark had played a relatively prominent role in the negotiation process, and it was the Danish diplomat Skjold Mellbin who, on behalf of the EC, had acted as chief negotiator on the issue of easing cross-border personal interactions and contacts across the Iron Curtain. The entire concept behind the so-called Helsinki process, which led to the final declaration, was tailored to the internationalist aspects of Danish foreign policy, namely by the initiation of dialogue about détente and disarmament in Europe, increased trade relations and improved human interaction. This last point could be seen as a small step towards addressing the issue of human rights, though the Eastern bloc formally refused to discuss this topic.

African diplomacy, the New International Economic Order and development aid

Unlike America, Denmark and the other Nordic countries supported a number of left-wing African liberation movements and governments. This was based on a desire to fight colonialism and apartheid but also to prioritise dialogue in the context of the Cold War. The Nordic view was that a failure to support dialogue would simply push such movements and regimes further into the arms of the Soviet bloc. With these objectives in mind, Anker Jørgensen’s minister of foreign affairs, K.B. Andersen, pursued a very active African diplomacy.

The anti-colonial agenda was generally strong in the 1970s, when countries in the developing world were for a time able to dominate the UN agenda with a demand for a New International Economic Order (NIEO). This demand was based on a desire to further development and decrease dependence on Western capital, goods and technology, which were perceived by developing countries and many developing country organisations in the West as tools for exploitation. Danish governments acknowledged the problem but never wholeheartedly supported the requirements of the NIEO, since some of them meant breaking with general principles of the market economy. On the other hand, despite the oil crisis, 1978 became the year in which Denmark met the UN recommendation for wealthy countries to allocate 0.7% of their GDP to development aid. This was a further indication of the strong internationalist element in Danish foreign policy.

The escalating Cold War and re-armament

While Danish development aid continued to increase, to the point where it almost reached 1% of annual GDP at the beginning of the 1990s, the Danish foreign policy focus shifted away from developing countries in the 1980s. This was mainly due to the fact that the Cold War moved once again towards conflict from the end of the 1970s. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the election of Ronald Reagan as the president of the USA in 1980 contributed to increasing tensions between East and West, as President Reagan pursued a stronger confrontational line in the Cold War conflict.

In Denmark, the issue of nuclear re-armament became particularly controversial. In 1979, NATO took the so-called ‘double-track’ decision to deploy a new generation of medium-range ballistic missiles (or INF weapons) in western Europe unless the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact agreed to remove their new, recently deployed generation of medium-range ballistic missiles (called SS20s). The governments led by Anker Jørgensen were critical of the new turn in the Cold War, and particularly of the new wave of nuclear re-armament, but despite their reservations they chose to support NATO’s double-track decision.

The Cold War in Denmark

In this film, Cold War historian Rosanna Farbøl discusses how the Danish society prepared for and responded to the Cold War. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about 13 minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The ‘footnote policy’

In the years after 1982, the Schlüter governments attempted to move closer to the NATO position on nuclear weapons. This was not easy to achieve in practice, since by this time the previously mentioned ‘alternative majority’ had been formed in the Folketing, consisting of the Social Democrats, the Social Liberal Party and a number of smaller left-wing parties. This majority, under pressure from the strong peace movements of the time, forced the government to distance itself from NATO policy, especially its nuclear weapons policy, by introducing footnotes that expressed Danish reservations to NATO’s decisions – hence the name ‘footnote policy’. This was carried out through national security motions in the Folketing. A total of twenty-three such motions was adopted between 1982 and 1988, which greatly aggrieved the government and particularly the minister of foreign affairs, Uffe Ellemann-Jensen.

As previously mentioned, it was relatively unusual for a government not to accept the consequences and resign once its policies were in the minority. In 1988 however, when the Cold War was coming to an end and the Social Liberal Party had signalled that it wanted to leave the 'alternative majority', the government called the so-called 'nuclear election', with the aim of securing a more solid NATO mandate. This aim was achieved when Venstre, the Conservative People's Party and the the Social Liberal Party were able to form a coalition government after the election. All the same, the footnote dispute left a long and bitter taste, with both sides arguing that Danish domestic policy and party power struggles had been allowed to define Danish foreign policy, particularly NATO policy.

A peace demonstration in the streets of Aarhus in 1984. Peace movements mobilised strongly and visibly in the 1980s in Denmark, as in other Western countries, and helped to mount a critical challenge to the modernisation of NATO’s nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union also attempted to influence the peace movements, while the communist government in the Kremlin cracked down on equivalent movements behind the Iron Curtain. Photo: Jens Tønnesen, Aarhus City Archives

The fall of the Berlin Wall and active internationalism in military clothing

The ideological Cold War conflict between the communist East and the capitalist West ended in the years following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The end of the conflict forced Denmark to re-think and re-define its foreign policy, albeit without any fixed points of reference, since the international system was in flux, both in the neighbouring region and globally. Minister of Foreign Affairs Ellemann-Jensen described this task as like trying to paint a moving train. With the weakening and fall of the Soviet Union, there were plans to re-think and modernise Denmark’s most vital international collaborations in NATO, the UN and the EC, as well as to reconsider its relationship with the reunited Germany.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, Danish foreign policy gradually became more daring and activist. The goal was that it should support a new global agenda characterised by democracy, the defence of human rights and the securing of the international rule of law with the UN as its focal point. In other words, Denmark wanted its foreign policy to demonstrate its internationalist orientation. Examples of this policy in action between 1990 and 1992 include the whole-hearted efforts to ensure that the Soviet Baltic republics could regain their independence; the deployment of the Danish warship Olfert Fischer to the Gulf during the first Iraq War; and military involvement in the civil war that broke out in Yugoslavia. It was possible to militarise Danish foreign policy in this way because, for the first time in the twentieth century, there was no great power threatening Danish territory. Denmark could thus organise its own foreign policy without fearing military retaliation.

Tanks, diplomacy and aid

Denmark’s military commitment continued under the Nyrup Rasmussen governments in the 1990s, during which time Minister of Defence Hans Hækkerup was a particular driving force. Among other things, Hækkerup insisted that the Danish soldiers who participated in the UN missions in the Balkans should be heavily armed with tanks. In 1994, these tanks came into action against the Bosnian Serbs near the city of Tuzla, in the first major armed conflict involving Danish soldiers since 1940.

Denmark’s military engagement was followed up with major diplomatic initiatives. Under the slogan of ‘active multilateralism’, Nyrup Rasmussen’s governments attempted to expand and support international collaboration. The view was that the end of the Cold War offered a unique opportunity to promote international democratic peace and the rule of law based on dialogue and binding international collaboration, particularly through the UN. As described previously, foreign policy was conducted not only by the ministry of foreign affairs and the ministry of defence but also by the ministry of the environment, since environmental and climate policies were viewed as key priorities. In the 1990s, Denmark also became the top donor of official development aid in relative terms, with an annual aid percentage that exceeded 1% of GDP.

International activism and loyalty to the USA

After the terror attacks against the USA on 11 September 2001 and Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s almost simultaneous takeover of government in Denmark, Danish foreign policy once again changed character. Denmark’s orientation towards the UN and its goal of realising an international legal order became less important. Instead, foreign policy became primarily about standing shoulder to shoulder with the USA. It had already begun to shift in this direction in 1999, when Denmark took part in the bombing of Serbia as part of the conflict in Kosovo, without a UN mandate. The shift was completed when Anders Fogh Rasmussen took over as prime minister. For him, solidarity with the USA was almost a moral issue; in his speeches and writings, he persistently returned to the footnote politics of the 1980s as an example of Danish disloyalty and weakness in relation to its main ally. He was determined that this type of politics should never be repeated.

Fogh Rasmussen’s comparison was certainly effective, but also contrived on a number of points. First, most of the NATO countries – indeed all except Britain and Denmark – chose not to send combat forces to the second war in Iraq, which began in 2003. This was because they believed intervention without an explicit UN mandate went against international law, and because they were unconvinced by the American argument that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and was acting as a breeding ground for the terrorist movement al-Qaeda. Second, the Danish contribution to the war, consisting only of the small warship Olfert Fischer and the submarine Sælen, appeared largely symbolic, but nonetheless allowed Denmark to be included in the USA’s ‘Coalition of the Willing’.

At war

The Danish decision to send troops into the Iraq War must be seen in light of the 9/11 attacks on the USA in 2001. The attack was orchestrated by the al-Qaeda network from its base in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, and caused around 3,000 casualties. The American government felt compelled to retaliate. It did so by attacking Taliban forces from the air, and subsequently by forming a coalition for a land invasion in Afghanistan with the code name ‘Enduring Freedom’. The 9/11 attacks took place while Nyrup Rasmussen was still prime minister, and the view of the Social Democratic government at the time was that Denmark should support the USA, based on Article 5 of the NATO treaty (the ‘Musketeer clause’ on collective defence) and Article 51 of the UN treaty (the right to self-defence). When Fogh Rasmussen took over as prime minister a few months later, he accelerated the process and attained parliamentary approval to send aircraft and special forces to join the American-led operation.

The question of whether to participate in the Iraq War just over a year later was an entirely different matter, however. Only Venstre, the Conservative People’s Party and the Danish People’s Party voted for participation in the war. In other words, the issue of Denmark’s role in the conflict had become a matter for bloc politics, which was highly unusual for an issue of such national importance. Overall, this showed that foreign policy had become a central part of the value clash arena. Denmark participated in both wars for several years. It withdrew from Iraq in 2007 after losing seven soldiers there, while its role in Afghanistan continued as part of a NATO mission until 2014, at which point the last of its combat soldiers were removed from the country. Denmark lost forty-three soldiers as part of its military efforts against the Taliban in Afghanistan, including Sophia Bruun, the first woman to lose her life as a Danish soldier in action.

After 2014 Denmark remained active in Afghanistan, offering military and police training and development support for democracy, women’s projects and reconstruction, meaning that the country became one of the largest recipients of Danish development aid. This engagement was temporarily halted when President Biden, following a decision by the Trump administration, enacted a hasty withdrawal of the limited number of remaining American troops from Afghanistan by 31 August 2021. The decision was seriously criticised by many European – including Danish – politicians, since it led to a chaotic withdrawal from the country and an easy opportunity for Taliban forces to regain control.

The ‘war on terror’

The increase in development aid to Afghanistan was not matched by an increase in Danish development aid more generally. On the contrary, under Fogh Rasmussen, the level of Danish development aid fell for the first time since the 1960s. This was due to the influence of the Danish People’s Party, but also to a broader right-wing consensus to convert aid savings into funding for Danish welfare.

In general, there was a renewed focus on national territorial security. This was partly based on the impression that Russia, under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, was advancing aggressively, which required Denmark to reconsider its national defence. It was also due to the threat of terrorism. The attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York and the Pentagon in Washington in 2001 were carried out by a terrorist movement, al-Qa- eda – in other words by a non-government actor. This placed new demands on national security, since the Islamic terrorist groups projected their struggle onto the Western countries’ own territories, as underlined by a series of attacks in Spain, Britain and France, among others. Denmark was also affected on several occasions, such as in the attempted murder of the Islam-critical author and historian Lars Hedegaard in 2013, and in the attacks on the cultural centre Krudttønden and the synagogue in Copenhagen in 2015, in which three people were killed.

The Cartoon Crisis

Denmark had become an obvious target for terrorism, as a result not only of its active participation in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but also the attention it received following the Cartoon Crisis. In 2005, the daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten published twelve satirical drawings of the Islamic prophet Mohammed in the name of freedom of expression. This led to violent demonstrations in the Middle East, where Danish flags and embassies were burned. Danish goods were boycotted, and diplomatic pressure was put on the country. It was undoubtedly the largest diplomatic crisis Denmark had found itself in since the Second World War.

Terrorism and the fight against it have had huge costs in both the Middle East and Denmark. In Denmark, many resources have been used to avert terrorism, and legislation has been tightened several times since the first anti-terrorism package was passed in 2002. As a result of this package, the scope of police and intelligence surveillance of citizens in Denmark has been expanded considerably.

The EC/EU – between yes and no

When the Danish electorate voted to join the EC in 1972, they did so with a large majority. It was not long, however, before opinion polls began to show increasing resistance to the Danish membership. The oil crisis, which occurred during Denmark’s first year in the EC, most likely played a role in this resistance, since it obscured the economic gains Denmark had actually reaped through its membership, particularly through improved export opportunities for the agricultural sector.

Despite emerging scepticism towards the EC, there was another ‘yes’ vote when the Schlüter government called a referendum on the establishment of a single market via the Single European Act in 1986. In the Folketing, however, there was a majority against it, since both the Social Democrats and the Social Liberal Party opposed it. They believed the act contained insufficient provisions for environmental protection, and that it paved the way for a European union through its stipulations for member states’ co-operation on foreign policy and the expansion of the legislative powers of the European Parliament. To the surprise of many observers, the Schlüter government managed to secure a ‘yes’ in the 1986 referendum – which was consultative and not called on constitutional grounds.

Conflicts over the Maastricht Treaty

In the final days of the referendum campaign in 1986 Schlüter declared that the Union would be ‘stone dead’ if the Danes voted ‘yes’. He did so to defuse fears about a European union, which was always highlighted by the ‘no’ side as a great threat to Danish sovereignty and independence. Schlüter regretted this remark about the union, as it hit him like a boomerang when the Danish people were once again called to a referendum in 1992 on the Maastricht Treaty to establish a European union. The treaty was a result of the major changes that had taken place in Europe as a consequence of the fall of the Berlin Wall, including German reunification, the liberation of eastern Europe from the Soviet Union, civil war in Yugoslavia and the expectation of declining American interest in Europe. In light of these new challenges, the Maastricht Treaty attempted to increase both the scope and level of European collaboration and integration by creating a political union.

Among other things, the treaty contained provisions to expand legal and police collaboration, as well as foreign policy and security collaboration, potentially by establishing an actual joint defence capability in the long term. These provisions involved inter-governmental cooperation in which decisions would require unanimity, and in which the Commission, the Court and the Parliament would have extremely limited influence. On the other hand, these institutions would enjoy increased influence in the EC’s hitherto core areas related to the single market. In these core areas, collaboration was intended to be more supranational, so that member states had to hand over more sovereignty to EU institutions, which would all enjoy greater influence on the legislative, administrative and judicial practices of collaboration. This was considered necessary in order to streamline and strengthen the EU’s decision-making capacity. The most far-reaching proposal within this framework was to establish an economic and monetary union (EMU), with a single currency, within a period of years. This ambition was a logical extension of the desire to strengthen the single market, but it was also a step towards in-depth integration.

The increased politicisation and supranationalisation of European collaboration was more than the Danish voters could accept, and at the referendum on 2 June 1992, 50.7% voted ‘no’ to the Maastricht Treaty, corresponding to a majority of approximately 50,000 votes. This was a problem for the EU and for Denmark. The transition from the EC to the EU required unanimity among member states; on the other hand, it was clear that the other countries would not let such an important reform be held back by Denmark. The Danish government was therefore asked to find a solution.

When the Danes voted ‘no’ to the Maastricht Treaty, it was the unenviable task of Venstre’s minister of foreign affairs Uffe Ellemann-Jensen to resolve the Danish situation for the other EC countries. He did this at the European Council summit in Lisbon on 12 June 1992, among other occasions. In front of the waiting world press, he uttered the famous words: ‘If you can’t join them, beat them’. This statement, along with his clothing, was also intended as a comment on the final of the European Football Championships, which was to be held later that day. In a surprising victory, Denmark won this final against Germany with a score of 2–0 – a result that perfectly reflected the minister’s statement. Still photo from the television news on 26 June 1992, Danish Broadcasting Corporation

The national compromise in 1992

The solution was the so-called ‘national compromise’, a political agree ment negotiated between the Social Democratic Party, the Social Liberal Party and the Socialist People’s Party. The basis of the agreement was that Denmark should be granted four opt-outs in relation to the Maastricht Treaty – namely on joint defence co-operation; on supranational aspects of joint policies related to justice and home affairs; on joining the third phase of EMU collaboration (the introduction of the euro); and, finally, that joint EU citizenship should not apply to Danes. At a meeting of the European Council in Edinburgh in December 1992, the EC countries finally accepted these Danish opt-outs.

The national compromise was highly unusual in that it was negotiated and put in place by the opposition. The Venstre–Conservative People’s Party government had no real influence over the agreement, but had to accept it if they wanted to secure a ‘yes’ vote in a new referendum. The agreement had to attract more ‘yes’ votes, especially from Social Democratic and Socialist People’s Party voters if it was to succeed. This also happened at the new referendum, the so-called Edinburgh referendum of 18 May 1993, when 57% of all votes cast were in favour of the national compromise. Following this result, violent anti-EU demonstrations broke out in the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen, during which the police fired live ammunition at the demonstrators – an episode that showed how radically polarised the EU issue was.

European dilemmas

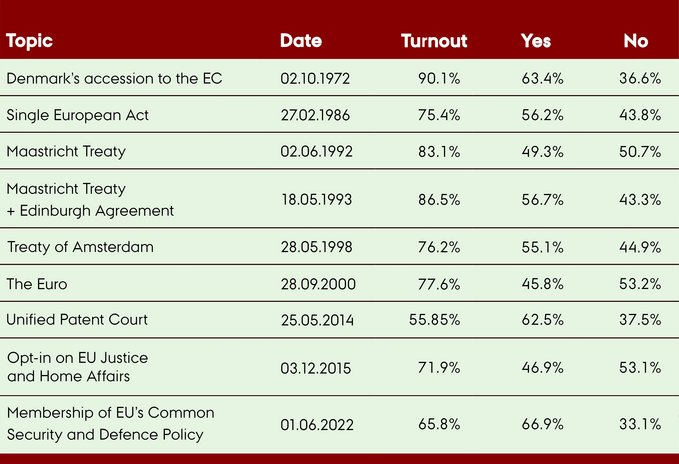

In total, Denmark has held nine referendums on the EC/EU. Six of these resulted in a ‘yes’ (in addition to those held in 1972, 1986 and 1993, there were also referendums on the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1998, the Patent Court in 2014 and the lifting of the defence opt-out in 2022) and, as previously mentioned, three of them ended in a ‘no’ (in 1992, 2000 and 2015). After the two referendums on the Maastricht Treaty, opposition to the EU gradually moved from the left to the right, with the Danish People’s Party as the main opposing force, while support for anti-EU movements such as the People’s Movement against the EC and the June Movement began to subside. However, opposition to the EU was, as before, mobilised around the EU’s alleged threat to the welfare state and Danish sovereignty more generally.

After the expansion of the EU to include countries in central and eastern Europe in 2004 and the impact of the financial crisis in 2008, this threat was perceived more specifically as the issue of so-called ‘social dumping’ or ‘welfare tourism’. The concern was that workers from eastern Europe would come to Denmark and claim welfare benefits, such as child allowance, which they could then send home to Poland or Romania, while their presence might also contribute to a reduction in wages in Denmark. When these concerns were expressed, it was often forgotten that Danes could also receive child allowance from other EU countries if they happened to be working there; for example, from Germany, where child allowance was even higher than in Denmark. Conversely, Danish business organisations found it difficult to imagine how they would fill jobs in the hotel industry and the construction sector without foreign labour from eastern Europe and elsewhere. This therefore created rather an ironic dilemma, since it was apparently problematic when eastern Europeans came, but also when they went home. In 2020 close to 250,000 foreign workers were active in the Danish labour market (calculated as full-time workers), of which 70,000 were from eastern Europe.

Danish European politics has been somewhat directionless since the financial crisis. Under the Thorning-Schmidt government, the right-wing parties, including the typically pro-European Venstre, became significantly more sceptical of the EU in their rhetoric and their approach to EU collaboration. This changed when Venstre re-entered government, at which point Løkke Rasmussen publicly lamented that the EU had not been sufficiently valued. This public declaration was primarily due to Trump’s accession in the USA and the chaos that prevailed in the UK following the Brexit referendum in 2016. Since these events, the widespread attitude in Denmark seems to be that, in an unstable world, it is good to have friends and a solid anchor. Such an attitude was underlined at the European parliamentary elections in 2019. At the election the EU-sceptical Danish People’s Party suffered heavy defeat losing three of its four seats in the European Parliament, while The People’s Movement against the EU for the first time since the introduction of direct elections in 1979 failed to be represented. The more EU-positive trend was ultimately underlined in another referendum in 2022 when Danish voters voted with an overwhelming majority of 67% to lift the opt-out on EU defence co-operation. The war in Ukraine had a major effect on this re-orientation in Danish EU policy.

Danish referendums on the EC/EU. In total, nine referendums have been held on the issue of the EC/EU in Denmark. Data collected from: EU-Oplysningen, the Folketing

♦ Exit – The global challenge

This text went to press at a time of great change and upheaval in 2023. These changes could be registered at all levels of society – socially, economically, technologically and politically – while international relations also seemed increasingly strained. The thrust of globalisation appeared to be abating as protectionism gained new momentum. Free trade, which had been championed by the West since the Second World War, and became a global goal following the end of the Cold War, was no longer considered self-evidently good, but gave rise to all kinds of strategic concerns. The main reason for this was that geopolitical rivalry was intensifying between the West, China and Russia – and the rest of the world positioned itself in relation to this. The Russian military attack on Ukraine in 2022 was the latest and most serious manifestation of this trend, having resulted in direct economic warfare between the West (supporting Ukraine) and Russia.

At the threshold to the 2020s many countries around the world also saw internal protest and riots. Some of these had their origin in authoritarian rule and political repression – such as those in Hong Kong and Iran – while others were rooted predominantly in the social and economic effects of globalisation policies, including growing inequality. Latin America was a case in point, but European countries such as France (which saw the yellow vests’ revolt) or Britain (which experienced long and widespread post-Brexit strikes) were also affected. So too was the USA, with a temporary culmination during the Trump presidency of 2017–2021. During this period President Trump wanted to put ‘America First’ – a goal which was explicitly directed against the open globalist neoliberal approach American governments had pursued since at least the 1980s. But the slogan ran deeper, also functioning as a catchphrase for the re-formulation and re-traditionalisation of American values related to culture, race and gender. The USA became an epicentre of political strife in these years, in which fake news and the social media played a new and very prominent role. It all culminated in the storming of Congress on 6 January 2021, as a consequence of the president refusing to accept the election result of a constitutional, democratic process.

Denmark is not and has never been an isolated island in the world; Danish politics and society also struggled with the process of globalisation. There were particular challenges in reforming the Danish welfare state. Historically, it had been managed rather well in the period of globalisation, due to a strong economic performance which maintained Denmark’s position as one of the wealthiest countries in the Western world. Part of this success story was related to expansion in key economic sectors linked to the new ‘green’ economy, such as wind turbines, water pumps and thermostats, but also pharmaceuticals (from, for example, Novo Nordisk). Despite the growth of inequality and the increasing concentration of wealth in the urban centres, Denmark still ranks among the most socially equal states in the OECD group.

In the future Denmark will have to be very inventive to continue to succeed in adapting its welfare state to the realities of the twentyfirst century. As in many other European countries, the ageing of its population is a challenge. In the coming years the number of people in the labour market will be reduced, while the number of pensioners will grow. In 2023 this was already causing pressure and bottlenecks in the health sector. One way of addressing this would be to allow more immigration, but – as shown in this module – if there is one field where Denmark has struggled to cope with the effects of globalisation, it is precisely in the area of immigration. Since the turn of the century, a great deal of Danish political debate has been determined by value or identity politics; much of this has revolved around coping with immigration, as well as finding ways and means of reducing immigration. The paradox is that immigration may be conceived as a threat to the welfare system, but at the same time it also presents itself as one of the most readily available measures to address welfare state bottlenecks.

Identity politics have also played a significant role in the Danish approach to the EU and European integration. Denmark has been Europeanised to a considerable extent through its membership of the EU, and battles have been waged to keep as much national sovereignty and independence as possible. The opt-outs to membership granted in 1992–1993 demonstrate this, as do the vain attempts by governments to lift them at referendums on the Euro in 2000 and on justice and home affairs in 2015. Since then the European winds have changed and at the beginning of the 2020s Danes had come to feel more positive about the EU. This seemed to stem from a combination of international factors: Brexit-related chaos, the European insecurities provoked by the Trump presidency, the COVID-19 pandemic and finally the outbreak of war in Ukraine. The latter event paved the way for the lifting of one of the Danish EU opt-outs for the first time – that of keeping out of EU defence co-operation.

The extent to which politics was re-defined in these years to cope with the combined challenges of welfare state reform, climate change and war in Denmark’s European backyard is best exemplified by the new government which took office in December 2022. The election result was quite remarkable, as it granted representation to no fewer than twelve parties – of which only the Social Democrats received more than 20% of the vote (27.5%). The rest were all grouped between 2.6% (the Danish People’s Party) and 13.3% (Venstre). Even so, Prime Minster Mette Frederiksen decided to create a majority coalition government with Venstre and Moderaterne (a new party formed by former Venstre prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen).

Majority governments, as well as governments including both the Social Democratic Party and Venstre, have been extremely rare in Danish history. In fact the latter combination has existed only at times of dire crisis (the late 1970s) and war (during the two World Wars). This recent government formation in itself thus testified to a feeling that great challenges lay ahead.