3. Growth and welfare dilemmas

The period after 1973 saw economic upturns and downturns. Economic growth could not match the ‘golden age’ of the 1960s; it was sluggish and uneven, especially in the 1970s and 1980s. Nevertheless, Denmark managed to maintain its position as one of the richest Western countries, among other reasons due to its ability to adapt to and exploit the EU’s single market and globalisation. This process of adaptation demanded continuous change. In the 2010s climate change began to challenge the growth paradigm itself – in other words the idea that constant economic growth is essential to ensure a country’s wealth. This affects the entire foundation of the welfare state, which – as a result of globalisation, taxation policy and pressure for increased spending on elderly care and health – had also become diluted and less inclusive over time. In 2020 and after, Denmark managed to cope with both the economic and the public health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic reasonably well, due to massive public aid packages and widespread testing and vaccination. The Danish economy was robust enough to cope, but was challenged by yet another crisis: the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022. This sent energy prices soaring and inflation generally rising, and created demands for further state intervention on a scale not seen since the energy crisis of the 1970s.

Growth and problems of economic balance

Throughout the entire period from the 1970s until 2020, Denmark was in the top ten among the richest OECD countries, regardless of whether this was measured by GDP (Gross Domestic Product) or GNI (Gross National Income). According to the OECD, Denmark was the third-richest country in the EU in 2004 (measured by GDP) and the seventh-richest OECD country in 2016 (measured by GNI).

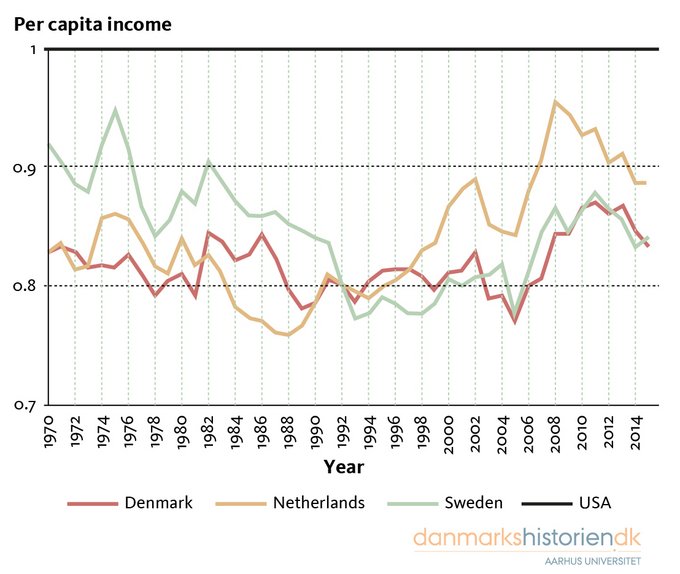

Per capita income in Denmark, Holland and Sweden compared with the USA, 1970–2014 (index USA=1). As the graph shows, per capita income in the three wealthy western European countries was below that of the USA for the entire period, and there were fairly large fluctuations between the three European countries. For example, per capita income in Sweden was higher than in Denmark until the 1990s, at which point the Swedish economy was affected by the same economic problems Denmark had faced in the 1970s. The graph shows nothing about the distribution of income within the respective countries, which was more unequal throughout the entire period in the USA than in the three European countries. © danmarkshistorien.dk based on figures from Statistics Denmark.

This does not mean that the path was always smooth, however. In the 1970s and 1980s, Denmark faced recurring economic problems in the form of state budget deficits, balance of payments deficits, rising external debt and high unemployment, all of which were exacerbated by a sharp rise in interest rates. It was against this backdrop that the recently resigned minister of finance, Knud Heinesen (Social Democrats), claimed on prime-time television in 1979 that Denmark was heading for the abyss. Heinesen was particularly concerned about the sharp increase in external debt (private and public debt to foreign creditors) and public debt (at state, county and municipality level), which diminished economic policy choices and risked making Denmark dependent on foreign borrowing to the extent that the country – like Greece after the financial crisis in 2008 – might lose the ability to decide its own economic policy.

The problems in the 1970s were exacerbated by sudden and sharp increases in the price of oil during the so-called oil crisis, which also affected other western European countries. As we have seen, the 1960s was a decade of unusually strong economic growth, with annual growth rates of 4–5%, yet this decade also saw a number of economic problems at both national and global level. At the national level, there was a persistent balance of payments deficit and increased public spending, and at the global level there was turbulence in the monetary system following the severe weakening of the US dollar. These challenges resurfaced in earnest with the two oil crises, which began in 1973 and 1979. As a result, the Danish economy experienced negative growth for a few years in both the mid-1970s and the early 1980s. Overall, however, the Danish economy grew by around 2% in GDP in the 1970s, which was even higher than in the 1980s, when the average annual growth rate was just over 1.5%.

Mærsk drilling platform in the North Sea. Knud Heinesen’s doomsday scenario faded in the 1980s, not only due to Schlüter’s fiscal austerity and improved international economic conditions, but also because the 1980s became the decade in which oil and gas extraction was boosted in the Danish part of the North Sea. While A.P. Møller-Mærsk and the other oil companies in the Danish Underground Consortium (DUC) generated high revenues, the state treasury also received money from the hydrocarbon tax and various other duties, and Danish oil and gas became essential in tipping the balance of payments from abroad from negative to positive. The state’s revenue from the North Sea peaked in 2008, and in 2017 A.P. Møller-Mærsk sold off its activities in the DUC to the French company Total. Photo: Claus Fisker, Ritzau Scanpix

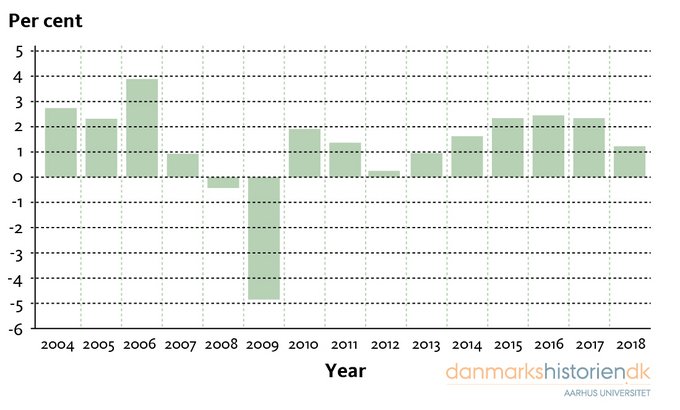

In the 1990s, average annual growth rose to just over 2.5%, according to Statistics Denmark. Until the year before the financial crisis, growth was generally high, but it became negative for the period of the financial crisis (2008–2009), before gradually returning. From 2015, the figures have been solid, with an annual growth in GDP of over 2%, according to subsequent corrections of national accounts conducted by Statistics Denmark.

Annual development of GDP as a percentage from 2004 to 2018. This illustration includes Statistics Denmark’s revisions of earlier accounts. Compared with previous accounts, growth since 2014 is now estimated to be significantly higher, which not least illustrates Statistics Denmark’s difficulty in estimating the value of the Danish economy’s global activities. The diagram thus shows that the Danish economy recovered from the financial crisis more quickly than was assumed before the revisions in 2018. © danmarkshistorien.dk based on figures from Statistics Denmark

Gross Domestic Product and Gross National Income

Revisions of the national accounts show that preparing such accounts is no easy task, and the task has been made even more difficult by the increasing number of transactions being made across national borders. Despite this, GDP is still used as the international standard measure for economic activity in a given country or region. It should be noted, however, that GDP, which measures the value of production, is not the most reliable indicator of a country’s prosperity. For this, it is more accurate to use Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, since this figure also includes the value of international financial transactions measured per capita.

Earning income from abroad is important for Denmark, and compared with the 1970s the country is now doing well on this measure. This is because it no longer has a large debt burden to repay to foreign lenders, and because Danish companies and pension firms bring more money to Denmark than that which leaves the country. At the end of the 2010s Denmark had a healthy balance of payments surplus, which – with the exception of 1998 – it had enjoyed since 1990.

The bumblebee that could fly

Denmark’s retaining of its position among the richest countries in the EU and OECD amidst changing economic conditions is mainly due to the ability of the Danish economy to adapt to international competition and technological change. This ability has surprised many economists, since Denmark has had some of the highest public expenditure and therefore one of the highest tax burdens in the world throughout the entire period. According to neoliberal economic thinking, such a combination is an obstacle to investment and growth. In this sense, Denmark – like the other Nordic countries – has been like the bumblebee, which despite its heavy appearance still manages to fly.

Denmark’s high public expenditure and high taxes are connected to the expansion of the welfare state, which took place in earnest throughout the 1960s and the early 1970s. This was also the cause of Glistrup’s tax revolt in the 1970s, though the impact of the revolt remained marginal within the bigger picture.

In its broader sense, the welfare state is not only about social benefits but also education, the labour market and policies that have ensured a well-functioning and cohesive state. It has been expensive to build and has resulted in a large public sector, but it has also created frameworks that have proved essential for the private manufacturing and service sectors. These sectors have profited from a well-educated labour force, from reliable and updated transport and communication networks, from the free trade policy that the Danish government has continually pursued and from a well-functioning state that has ensured law and order.

Infrastructure and flexicurity

One example of the state’s active commitment to providing an effective framework for production was the large investments it made in transport and communication infrastructure. Throughout the period, the transport network expanded considerably, and investments were made in new motorways and major bridge construction projects. After many years of political debate and controversy, the Great Belt Bridge (Storebæltsbroen) from Fyn to Sjælland finally welcomed train passengers in 1997 and motorists the year after, while the Øresund Bridge to Sweden opened in 2000. Another significant development has been the digital transformation, which the state has actively promoted. As such, Denmark has one of the most digitalised public sectors in the world, and in 2018 the UN named Denmark the world champion in public digitalisation, while the EU Commission placed Denmark as the most digitalised country in the EU.

The Øresund Bridge was inaugurated in 2000. The bridge, which also connects to a tunnel, was an important part of the ambition to create a coherent and dynamic growth area in the Øresund region. In contrast to the Great Belt Bridge, it was initially difficult to get the Øresund connection to live up to traffic forecasts, but in 2017 the two bridges were used equally as much, with almost 12 million cars crossing them. Photo: Øresundsbron.dk

Another example is the state’s active engagement in the labour market. As mentioned above, unemployment became a major problem in the 1970s, reaching a rate of almost 10% of the labour force at the beginning of the 1980s. This increase was due to the oil crisis, but also to a rise in the number of people accessing the labour market, especially women, who could not be absorbed by the slow growth in the 1970s. Schlüter’s governments in the 1980s also battled with record high unemployment levels, with nearly 360,000 unemployed when his last government stepped down in 1993. During Nyrup Rasmussen’s governments in the 1990s, efforts were therefore made to create a more effective labour market structure. The government invested heavily in further education and training for unemployed workers, and it also shortened the period and tightened the conditions for receiving unemployment benefit. This approach gradually became known as the flexicurity model, which also resonated internationally, since the model seemed to lead to falling unemployment rates and decent economic growth.

The Danish model

The ‘flex’ part of ‘flexicurity’ captured the idea that Denmark had a highly flexible labour market with low job security compared with other Western countries, particularly in the private sector. People could lose their jobs at very short notice, but the ‘security’ part meant that these people were not left without economic support during periods of unemployment. This system was an effective tool for upskilling the labour force and combatting unemployment, and it contributed to the fact that, unlike many other European countries, Denmark succeeded in avoiding high levels of youth unemployment.

The flexicurity model was developed within what was widely understood as the Danish labour market model, which – as mentioned earlier in this volume – has been evolving since the end of the nineteenth century. In this model, it was largely left to the labour market partners to agree and implement labour market reforms, occasionally with the state as an active participant, expressing wishes or issuing demands that must be met. The alternative would have been to implement these reforms through legislation, as was customary in the EU and other European countries.

The Danish model came under pressure in the twenty-first century for several reasons. Firstly, the model was dependent on a high rate of trade union membership, but this had been declining since the 1990s. As a consequence it became increasingly difficult for the trade unions to represent and speak for the whole labour market. Secondly, many employees believed that the flexicurity model had become unbalanced, as several of the labour market reforms since the 1990s prioritised flexibility at the expense of security. For example, the value of unemployment benefits was eroded significantly. According to a 2018 report by the Economic Council (Det Økonomiske Råd), unemployment benefit for an industrial worker covered only 47% of lost earnings, as opposed to over 60% in the 1980s. Thirdly, the model also came under increasing pressure from the EU, which often required legislation instead of labour market implementation in a given area, based on the argument that the latter would not cover all workers but only those who were members of the main trade union organisations.

Putting the environment on the agenda

The concept of growth has increasingly become the subject of debate, especially in light of the major environmental and climate challenges of the period. The first wave of growth criticism emerged in the 1970s with the bestselling 1972 report Limits to Growth, which was compiled by international researchers in the Club of Rome. The report in itself did not really shake the supremacy of growth ideology, but it did help strengthen the trend towards a greater awareness of resources and the environment. In 1973, Denmark gained its first comprehensive environmental law. In this early phase, environmental issues were promoted by parties such as the Socialist People’s Party and the Social Liberal Party.

A number of strong environmental grassroots organisations emerged in this period, such as NOAH (the oldest Danish environmental organisation, from 1969) and Greenpeace, the Danish branch of which was founded in 1980. The most important organisation by far was Organisationen til Oplysning om Atomkraft (The Organisation for Information about Nuclear Power, or OOA), which was established in 1974 and which played a prominent role in the political mobilisation that led to Denmark effectively rejecting the introduction of nuclear power in the 1980s.

Pollution, climate and energy

The environmental debates and initiatives of the 1970s and 1980s were primarily aimed at combatting pollution – in other words, additives in food, the discharge of untreated sewage, polluting companies (particularly chemical companies such as Grindstedværket, Cheminova and Kemisk Værk Køge) and gradually also agricultural pollution and the leaching of nutrients into watercourses and fjords. It was the issue of leaching that, among other things, led to the comprehensive aquatic environment law in 1987. Overall, these larger environmental initiatives seem to have helped; in a number of areas, Denmark appears less polluted in the twenty-first century than it did at the beginning of the 1970s.

The second major impetus in the environmental debate came in the 1990s, with the recently unseated leader of the Social Democrats Svend Auken becoming a dynamic minister for the environment and energy in Nyrup Rasmussen’s governments. By combining the ministries of the environment and energy into one office, Denmark showed that issues of climate, CFCs which affect the ozone layer and CO2 emissions from the burning of coal and oil had become central topics in Danish (and international) environmental debates and policies. Auken was an active figure in the negotiations that led to the UN’s Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which aimed to set binding targets for reducing greenhouse gasses. In the domestic arena, he pushed forward wind turbine investments that had already been included in the so-called Energy Plan 2000 under Schlüter.

Growth and sustainability

It is often claimed that Denmark is an environmental forerunner in the EU, or even the world. But this is not the whole picture. In 2023 Denmark had ambitious climate goals. In 2017, 43% of electricity consumption in Denmark was provided by wind energy, and 30% of overall energy consumption came from renewable sources. The goal of the Folketing and Løkke Rasmussen’s third government (2016–2019) was that Denmark should be energy-neutral by 2050 (that is, it should store as much energy as it emits) and that, among other things, fossil fuels should be completely phased out by this time. Mette Frederiksen’s 2019 government added the goal that, by 2030, Denmark was to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 70% compared with 1990 levels.

This was an extremely ambitious target, even by the standards of other northern European countries and the EU. But the bar was set high, because Danes are among the world’s biggest contributors to human-derived climate change, with the average inhabitant racking up a large carbon footprint. The reason for this footprint is that, with their increased wealth, Danish citizens had become large-scale consumers of environmentally harmful goods and services, such as electronics, textiles, air travel and beef. In addition, because of growth in the vehicle fleet, the transport sector continued to be based on the fossil fuels diesel and petrol – a situation which has changed since 2020, with an increasing number of electric cars being sold. Meat and dairy production, which is extensive in Denmark, is also a sector which drives higher greenhouse emissions, and one which politicians are reluctant to confront.

The question going forward is thus whether Denmark and other wealthy countries can continue to organise economic policy based on traditional GDP growth criteria when some researchers and climate activists claim that it is precisely the growth and consumption ideology that is the problem. They argue that countries should put climate considerations before growth considerations. In 2015, the government itself conducted a pilot scheme in which it asked a number of researchers to develop a so-called green GDP. In the context of the climate debate, the problem with traditional GDP is that it does not distinguish between environment- and climate-damaging activities and sustainable activities. All these activities count when growth and wealth is calculated according to the standard GDP method.

Green transition

Despite the criticism of GDP, there is not necessarily a contradiction between the green transition and growth, since there is major growth potential in developing and implementing green technology. This is something that Danish companies specialising in wind turbines – like Vestas – or hydro and heat technologies – like Grundfos and Danfoss – have profited from, and it is also the reason that these firms have called for an ambitious green transition. Danish governments have underlined the importance of gradual change, preferably in line with the development of modern climate-friendly technologies, since the green transition concerns jobs and livelihoods and thus also the stability of society.

But the situation is critical, because global warming also has the potential to destabilise society and its national and global equilibria. Global warming does not respect national borders, and significant changes need to be made to production and lifestyle if Denmark and the rest of the world are to succeed in living up to the 2015 Paris Agreement to ensure that world temperatures do not increase by more than 2 degrees (and preferably only 1.5 degrees) compared with temperatures before the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. Denmark has ratified the UN’s Paris Agreement. However, during his time in office, President Trump withdrew the USA from the deal, which made it much more difficult to meet the goals of the agreement and itself exposed the mutual dependence between national and global politics in the global age. This difficulty was understood by the Biden administration in the USA, elected in 2020; one of its first acts of government was to sign up to the Paris agreement once again.

From ‘rotten capital’ to ‘rotten banana’

The standardised national figures for growth and welfare development hid the fact that the pace of development in Denmark displayed large regional differences and shifts over time. In the 1970s, industry moved to the west, from Copenhagen to Jutland, where there was more space and cheaper skilled labour. This development was supported by the political view that western Denmark needed an educational boost, which is why new universities were established in Odense (1966) and Aalborg (1974), and also in Roskilde in the east of Denmark (1972). Along with the two existing universities in Copenhagen and Aarhus, these institutions experienced a drastic increase in the number of students they educated, which concluded the transition from elite to mass higher education and also reflected the movement away from the industrial society to the knowledge society.

This development was difficult for Copenhagen; in the 1970s and 1980s it experienced stagnating population numbers, a dilapidated housing stock and lack of an updated infrastructure. The city itself was not able to break this negative spiral of development, but instead accumulated debts. This was seen as a problem because, on the international level, increased urbanisation was understood as a path to establishing a modern knowledge-based economy. It is in this light that the major projects to expand and modernise Copenhagen’s infrastructure should be understood. These were initiated by the Schlüter governments. Nourished by the ambition to make Copenhagen into a growth centre in a Danish-Swedish Øresund region, this resulted in, among other things, the privatisation of Kastrup Airport and decisions to build the Øresund Bridge, the Copenhagen metro and the new city area of Ørestad.

These projects, combined with a boom in the pharmaceutical and IT sectors, breathed new life into the city, and other large cities also experienced growth. In particular, the so-called east Jutland urban belt, which stretches from Kolding in the south to Aarhus and Randers further north, boomed, developing into a functionally coherent metropolitan area along the E45 motorway. Urbanisation hit other areas of Denmark hard, since some regions became increasingly depopulated and experienced significantly less growth. This development gave rise to the concept of the ‘rotten banana’, which figuratively stretched from Lolland-Falster over parts of Fyn to southern Jutland and up through west Jutland to north Jutland. After 2010, this concept was increasingly replaced by the term ‘Peripheral Denmark’ (Udkantsdanmark).

According to the national planning report Det nye Danmarkskort – planlægning under nye vilkår (The New Map of Denmark – Planning under New Conditions, 2006), Denmark had two dynamic centres of growth: one centred on the capital and one in east Jutland. These centres were not, however, entirely congruent with the boundaries of the new regions anticipated in the municipal reform of 2007, as shown by the white circles on this map. The report emphasised the importance of establishing cross-regional urban networks following the reform, in order to stimulate international competitiveness in the knowledge society and ensure a balance in Danish urban development. The colours show the five regions established in the municipal reform of 2007. Map published in: Landsplanredegørelsen 2006

Changing job structures and public centralisation

There is no doubt that Denmark’s economic development has become more skewed in the twenty-first century, since more jobs have been created in the knowledge and service sectors centred in the larger cities. In the early 1970s, around 10% of the labour force was employed in the primary sector (agriculture/fishing), but this had fallen to only 2% by 2018. The decline in secondary occupations (craft businesses and industry) has been even more pronounced over the period; in 2020 less than 20% of the population was employed in the secondary sector, while employment in the private and public service industry – the tertiary sector – had increased to around 80%. At the same time, many more women enrolled in education programmes and joined the labour force, which also helped to further urbanisation and empty the periphery.

The trend towards centralisation was supported politically, particularly by a major municipal reform that came into force in 2007. This followed in the footsteps of the reform of 1970, further centralising local self-governance and administration. It reduced the number of municipalities from two hundred and seventy-one to ninety-eight and abolished counties (amter) in favour of five regions, which were primarily given responsibility for the country’s health care system. The reform was designed to improve efficiency in the public sector, but it also contributed to depriving many local communities of important institutions, such as hospitals, police stations and educational institutions. It is for this reason that, after 2015, Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s governments attempted to counteract the centralisation trend and criticisms of it by moving public sector departments from Copenhagen to the provinces.

(In)equality

As well as being regionally skewed, the increase in growth and prosperity in Denmark has also became socially skewed and less inclusive. In terms of income equality, Denmark had always ranked highly among OECD countries. To measure equality of income, economists use an index called the ‘Gini coefficient’. If the Gini coefficient is 0, there is maximum equality; if it is 1 there is maximum inequality – meaning that just one individual earns all the country’s income. According to a 2016 report by the Economic Council, Denmark’s Gini coefficient based on disposable income (salaried income, capital income and transfer income minus tax) was 0.20 in 1970 but 0.27 in 2014. Despite this increase in inequality, which began in the 1990s, Denmark still occupied third place in the OECD after Iceland and Norway. But the Gini coefficient can also be calculated on the size of accumulated personal wealth; on this calculation, Denmark was actually one of the more unequal OECD countries, particularly due to inequalities in home ownership and pensions.

There are many reasons for the rise in inequality. It was driven by technological development, but also by the deregulation of the labour market and the availability of foreign labour, combined with the general weakening of the trade union movement. The fact that the return on financial investments rose more than wages was no doubt also a factor behind rising inequality. Just like tax cuts for the highest earners, this tended to favour those with the highest income and the most assets. A similar trend can be seen in many Western countries, where economic policy in the twenty-first century was focused heavily on increasing the labour supply. The logic was that people should be rewarded for being active in the labour market and for working longer, but this also created increased inequality for those who could not or did not wish to work more.

Growth and deceleration in the welfare state

As previously shown, the Danish welfare state was built as a tax-funded, universal welfare system. The last building block was laid with the Social Security Act (bistandslov), which came into force in 1976. The basic idea behind the reform was that the individual client’s (the new term used) or family’s need should be assessed using a holistic approach. The Social Security Act was therefore built on needs-based rather than rights-based assistance. Assistance could thus be better individualised and targeted. The overall aim was to seek to prevent the need for social security, and rehabilitate clients if they did. This benefitted citizens and state alike, based on the expectation that this would reduce the need to place citizens on permanent support.

The aim seemed reasonable but it was also expensive, especially during the crisis-hit 1970s when the main problem became the need to halt the post-war growth in welfare spending. In the 1980s, the Schlüter governments took on this challenge by reducing the value of various transfer payments and making the first day of sick leave unpaid, but they also conducted a thorough revision of the Social Security Act’s approach to needs-based assistance. This revision was continued under the Nyrup Rasmussen governments of the 1990s, when a new law on active social policy in 1998 enshrined the principle that social assistance was a right in given social circumstances but that the individual also had the responsibility to be personally self-sufficient and actively to seek longterm employment. The aim was a transformation from passive to active assistance, both in relation to the individual citizen but also as a way of keeping welfare expenditure in check and thus making the welfare state more sustainable and future-proof.

The (not entirely) universal welfare state

From the turn of the millennium, the welfare state once again ran into difficulties. Welfare spending remained high and difficult to manage, and the population was becoming older and more costly. At the same time, as described above, the political agenda was focused on lowering taxes and maintaining an iron grip on the state budget. Despite healthy GDP growth, there was almost no real growth in state budgets during Løkke Rasmussen’s third government, with noticeable consequences for the operation of everything from kindergartens to universities and hospitals. The combination of tax cuts, more elderly people and no increase in the state budget has meant that, in relative terms, there have been insufficient funds to maintain the welfare state at the same level as before. Private schools, private health insurance policies, private pension schemes and entitlement criteria (as opposed to rights criteria) for unemployment benefit, education support, the state pension and other transfer incomes have become more prevalent. Benefits for immigrants and refugees have been cut particularly drastically as part of an attempt to make Denmark a less attractive destination.

All of these factors not only helped to increase inequality – they also represented a threat to the universal foundations and basic conditions of the traditional welfare state. People’s incentive to pay high taxes decreases if they themselves pay into private schemes and generally have less contact with the state school system, the public health system or public transport. The incentive also decreases if the population feels that certain social groups are not contributing to the welfare state, either by abusing it or by not paying tax. On this point, politicians must take responsibility, because, through major budget cuts in the ministry of taxation – originally called efficiency measures (effektiviseringer) – they have undermined the ability of the ministry to monitor tax payments efficiently. This was demonstrated by a dividend tax fraud that occurred between 2012 and 2015, amounting to a loss of revenue of almost 13 billion kroner.