5. Cultural and social shifts

There were four major influences on the cultural and social norms of the post-war era: wartime experiences, high levels of economic growth, the welfare state and the youth rebellion. People enjoyed greater purchasing power, considerably better living conditions and more leisure time. There was also a shift in norms and class affiliation, as traditions and practices were questioned. This all meant that there were ruptures within the family set-up, the education system, the media landscape, art and popular culture.

The cultural youth rebellion

A particular kind of youth culture emerged in the 1950s, influenced especially by American trends. This manifested itself in the earliest rock music, the jitterbug dance and new fashions in clothing – leather jackets, blue jeans and swing skirts – that seemed provocative to older generations. A teenage culture emerged because fewer young people had to join the workforce immediately after their confirmation at the age of thirteen or fourteen, and a higher level of education along with better economic conditions gave many more young people self-awareness, dreams, leisure time and their own communities.

A more politicised youth culture emerged during the 1960s. For individuals, the youth rebellion implied a particular lifestyle, the identity markers of which were political attitudes, choice of education and job, appearance (such as clothing and hairstyle), accommodation, sex, friendships and music. In an intertwining of the local and the global, young people demonstrated against the Vietnam War, occupied university buildings, smoked hash provocatively on the steps of the ministry of culture, practised free love and lived in communes with shared clothing and biodynamic food.

The youth rebellion was therefore marked by many contradictions. On the one hand, it was based on community and solidarity, but it also paved the way for greater individualisation in relation to gender, class and family. An important part of the ideology behind the rebellion was optimism and faith in progress due to periods of relative peace, decolonisation, the spread of democracy and increased prosperity. At the same time, the movement also came to express pessimism, a critique of capitalism and doomsday prophecies of a devastating nuclear third world war. From the outset, the assessment of the importance of the rebellion varied. Was it about liberation and solidarity or egoism and indoctrination? Although it may sometimes seem that around 1968 many people found themselves on the barricades and abandoning gender roles, hierarchies and social etiquette, it is worth noting that the vast majority of the Danish population lived in traditional families with traditional working lives.

Better and larger homes

At the start of the post-war era the majority of Danes lived in small homes. It was not unusual for a family with several children to live in a two- or three-room apartment, and it was by no means given that a home had its own lavatory, running warm water or even access to a bathroom. In most homes, clothes were washed in large tubs or copper boilers in a shared basement or at the launderette. From the beginning of the 1960s, housing standards rose quickly. While only 62% of homes had their own lavatory in 1955, this figure had risen to 88% by 1970, and the proportion of homes with their own bathroom increased from 36% to 71% during the same period. Stoves and odorous paraffin, coal and coke were also on the way out; in 1955, 34% of homes had district or central heating, but by 1970 the figure was 84%.

The state mortgage scheme, which from 1938 helped families to buy small, single-family homes with relatively cheap state loans, continued until 1958. There was also a large increase in the amount of social housing, because politicians implemented quotas for subsidised housing after 1961. For large parts of the middle class, the new type of single-family detached house outside the city centre (parcelhuset) became an attainable ideal home. The number of square metres per person in the household grew, and individual family members enjoyed far more privacy than previously. Modern homes with domestic appliances such as refrigerators, washing machines, freezers and vacuum cleaners also decreased the amount of time needed for household chores, so people had more leisure time.

Overall, the post-war period saw a marked improvement in the quality of housing. Far more families were able to buy their own home and live in accommodation that was healthy, spacious and modern. Slums, overpopulated apartments, paraffin stoves and dark backyards became rarer in line with major redevelopment plans, and detailed urban planning sought to accommodate both the population’s desires and economic opportunities.

Family structure and family roles

Inspired by nuclear science, the English term ‘nuclear family’ referred to the family as a private, closed, biological unit. The term kernefamilie first appeared in Danish in 1956 and became the idealised family structure in the post-war era. Older ideas of the family, which encompassed servants and retired elders, were already disappearing due to industrial progress and welfare policy. This development, combined with a fall in birth rates, meant that families generally became smaller. It gradually became the norm for a family to consist of a father, a mother and two children. The nuclear family was not new, but reflected long-standing norms. It also only captured part of the reality, since children born outside marriage, single mothers, divorce and death meant that there were many other types of family.

In the 1950s, the ideal of the stay-at-home housewife emerged as a (lower) middle-class reflection of the role of women in the upper middle classes, and many women left the labour market to devote themselves to their house, husband and children. However, this was historically exceptional. Women had salaried jobs and played a key role in supporting their families financially before and after – and indeed during – the 1950s. Yet it was often the case that women worked fewer hours, had a lower level of education and earned less that the family’s male breadwinner. This influenced gender roles and status, as well as the division of labour in the home and the family.

Throughout the 1960s, communes and house-shares emerged as an alternative way to live, sometimes in large apartments and detached homes in large cities and sometimes in the countryside on farms and in abandoned manors. Areas designated for redevelopment were occupied in order to realise the youth rebellion’s ideas about freer forms of society. Squatters and hippies took over abandoned buildings. In 1971, the abandoned Bådsmandsgade Barracks at Christianshavn in Copenhagen were occupied and proclaimed as the Freetown Christiania. Christiania and Thylejren (Thy Camp), which emerged in 1970 in northern Jutland, presented social and political challenges, because the experimental ways of life practised there ran contrary to existing rules of society, for example in relation to psychedelic drugs, income control, paying for water and energy consumption, and housing standards and maintenance. Legalising these alternative ways of life therefore challenged the sense of justice in large sections of society and politics.

Family planning and reproduction

One of the most significant breakthroughs of the post-war era was that it now became possible to plan and control the size of one’s family. Unwanted pregnancy had historically resulted in unhappy marriages, dangerous illegal abortions and unwanted ‘illegitimate children’, because social, religious and moral norms prescribed ‘decency’ and marriage as prerequisites for a ‘proper family’. From the 1930s there was a gradual liberalisation of abortion legislation, so that women with specific health conditions or in specific family or social situations could have their pregnancy legally terminated in a hospital. After some years of discussions, in 1973 so-called ‘free abortion’ was introduced in Denmark, giving all women the right to an abortion within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy.

Safer, more accessible and easier forms of contraception also became more widely available. The contraceptive pill was introduced in Denmark in 1966. It became legal to advertise contraception in 1967, and in 1971 compulsory sex education was introduced in Folkeskolen (state primary and secondary schools). All these factors helped to influence the population’s view of sexuality, relationships and family patterns, so shame and stigmatisation played a less prominent role in society.

More than ever before, people could take control of their own reproduction. Changing possibilities and social norms were reflected in growing divorce rates, the number of unmarried couples and the higher age at which people got married. The increasing number of women in waged work also contributed to changing the traditional reproductive patterns, and the welfare state supported this change with support programmes for single parents, housing allocation and the building of day care institutions. Attitudes to children born outside marriage were beginning to change, meaning there was much less shame attached to visible evidence of premarital sex or becoming a single mother. Statistics show that 7–8% of children were born outside marriage in the early post-war years, but that this proportion had risen to around 15% by the mid-1970s. In 1960, children born outside marriage were given equal inheritance rights for the first time, and from 1964 they were no longer automatically monitored by the state until the age of 7.

The new women’s movement

The trend towards more gender equality continued in the post-war period. Legally and economically, women gained equal rights (and duties) in relation to tax, the state pension and the financial guardianship of children. In 1948, women were given the opportunity to join the newly created Home Guard (Hjemmeværn), based on the role women had played in civil protection and the resistance movement during the occupation; from 1962, they were also able to join the military. In 1948, the first female pastors were ordained. Denmark was one of the first countries to introduce equality within such traditionally male professions, but it did not happen without fierce debate and opposition from the military and the church.

A new type of women’s movement – referred to as the Red Stockings (Rødstrømper) by those both inside and outside it – emerged at the end of the 1960s. The name was directly inspired by the American Red Stockings, who were active from 1969 and whose name combined that of the earlier ‘blue stocking women’s movement with the red colour of the revolution. The movement was international, inspired by grassroots movements and the youth rebellion. Its aim was to achieve equal rights for women and men. This was nothing new, since the trade union movement, women’s organisations and many politicians had advocated equality for decades. What made the Red Stockings different was their unprecedented level of activism, using unconventional forms of organisation and deliberate provocations to attract attention and gain press coverage, for example through happenings, small group meetings, music and literature.

The Red Stockings had a major influence on the culture and society of the time. Gender roles for both sexes were re-defined and traditional expectations were challenged, but the actual, concrete impact of the movement is more difficult to determine. Women still earned considerably less than men, and there were very few female managers and politicians.

Women's Lives and Gender Roles

In this film, Astrid Elkjær Sørensen discusses women's lives and gender roles during the period from 1945-1973. The film is in Danish with English subtitles and lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Pornography and sexuality

There was extensive liberalisation within the entire sphere of sexuality. Sexuality came to occupy more of the public sphere, and stigmatization and shame were not as prevalent as before. Better contraception, access to abortion and sex education – along with the youth rebellion – contributed to more freedom and openness. In 1967, the Folketing abolished the ban on pornographic texts, and in 1969 Denmark became the first country in the world to legalise pornographic images. In the following years, pornography came to be associated with Denmark, resulting in a completely new commercial sector in the Vesterbro district of Copenhagen and at the German border, where Danes and tourists alike could buy risqué magazines and films.

Homosexuality became more accepted throughout the period. There was a trend towards greater legal acceptance, even though the legal age of consent for homosexual acts didn’t equal that of heterosexuals (fifteen years) until 1976. Until 1981, homosexuality was categorised as a psychiatric diagnosis. Gay people were subjected to discriminatory rules and procedures, through ‘the ugly law’ (den grimme lov) in particular, which from 1961 to 1965 criminalised homosexual prostitution more severely than the heterosexual kind and raised the age of consent in these cases. A ban on men dancing together in public – for example in dance venues and bars – was only formally lifted in 1973. In general, however, there was greater freedom and acceptance, which was partly due to general cultural and international currents and partly because the homosexual community was now more active and visible than ever before. This occurred in connection with the creation of special interest organisations such as the Federation of 1948 (Forbundet af 1948) and later the Gay Liberation Front (Bøssernes Befrielsesfront), which was founded in 1971 as a more political grassroots movement anchored in the youth rebellion and the gay community at Christiania.

Changes in schooling and curricula

In the 1940s and 1950s, it was not unusual to leave school at the age of thirteen or fourteen in order to start work or an apprenticeship. By the 1970s, however, it was rare for children to leave school so young, and better education became a norm encouraged by schools, parents and the state. Such a norm was introduced in the folkeskole (the municipal primary and lower secondary school) in 1958, when a new School Act abolished the special conditions in village schools, where children had not been entitled to the same range of subjects as in other schools, and where they often attended school only every other day in small classes with a wide age range. Middle schools were abolished, so the first seven years of school were the same for all pupils. After this it was possible to attend a formal secondary school or a vocational 8th and 9th grade, or to leave school. The last option was removed in 1972, when compulsory schooling increased from seven to nine years. During the 1960s, preschool classes were also set up in many schools, so that six-year-olds could get used to the school day and the teaching environment. Influenced by the cultural and political currents of the 1960s and 1970s, approaches to children and pedagogy were characterised by ideals of independence, problemsolving, group work and democracy rather than a one-sided focus on rote learning, times tables, arithmetic, handwriting and belief in authority.

An explosion of education on all levels

With some justification, one can refer to an ‘educational explosion’ during the 1960s. There were three major changes: more people received an education; more people studied for a longer period; and more women became better educated than before. In 1945, only approximately 4% of twenty-year-olds had an upper secondary school leaving certificate, while this figure had risen to over 21% by 1975. The same pattern could be seen in university education, where the number of enrolled students almost quadrupled over the same period. Three new universities were opened in Odense (1966), Roskilde (1972) and Aalborg (1974). While women quickly caught up with men at secondary school level, there were fewer who chose to progress to a university education – instead, they selected vocational programmes in order to qualify for women’s occupations such as nursing, social education or teaching. In addition, the number of unskilled workers fell, since many more people had the opportunity to take academic medium-term programmes in order to work in clerical jobs, or professional programmes in order to learn a particular trade or work in industry.

To a certain extent, this development broke social, economic and cultural cycles with regard to education level. It is important to note that students were increasingly less dependent on their parents’ support or – if they came from more humble backgrounds – on their ability to self-finance their studies through work on the side or successful applications for free university accommodation or private grants. In 1952, the Youth Education Fund (Ungdommens Uddannelsesfond) was established, which used the profits from the Danish football pools (Tipstjenesten) to distribute scholarships based on students’ applications and the fund’s discretion. In 1970, this fund was replaced by state education grants (Statens Uddannelsesstøtte, or SU), which became a part of the welfare state’s extension of equal rights to all. However, at that time, a student had to be twenty-eight years old – from 1975, twenty-three years old –before their parents’ income and assets were discounted in the grant calculation.

Consumer society

There were unprecedented increases in private consumption during the post-war period, mirroring the expansion of state spending. Like the rest of the Western world, Denmark became a consumer society. The relationship between prices and salaries resulted in large increases in real wages up to the 1970s, so purchasing power rose. The vast majority of people had more disposable income, and a smaller proportion of income was spent on food. Higher demands and expectations for housing and living standards meant that a significant part of disposable income was spent on house purchases or higher rent. Consumer goods such as televisions, travel and white goods also became part of family budgets. Private motoring grew rapidly – in 1945, there were 40,000 private cars in Denmark, or one vehicle for every one hundred people, but by 1973 one in four people had their own car.

The range of goods increased dramatically, and electric appliances such as vacuum cleaners, electric whisks, toasters and coffee machines gradually became commonplace in most homes. A new form of grocery and retail shopping also emerged. In 1949, the Esbjerg co-operative society opened Denmark’s first self-service grocery store, and the first real supermarket was opened by the Social Democratic minister of trade Lis Groes in the Copenhagen suburb of Islev in 1953. For the consumer, it was a completely new experience to walk around a shop with a basket or trolley and select from pre-packaged and price-labelled items such as meat, vegetables and bread under the same roof, instead of having to visit several smaller shops. The inspiration came from research trips to the USA undertaken by civil servants and representatives of the retail industry.

Cultural policy and cultural vision

The ministry of culture was established in 1961 as part of the expanding welfare state. The ministry was behind the creation of the Danish Arts Foundation (Statens Kunstfond) in 1964, which was intended to support performing artists through grants and work scholarships. State funding for culture had been available since absolute rule, but this funding now increasingly took the form of grants for young, experimental artists rather than honorary prizes for established artists, and an ‘arm’s length principle’ between the politicians and the grant committee was established.

The Danish Arts Foundation became the subject of heated debate, partly because tax revenue was being spent on artists and partly because it was being spent on artists that some viewed as left-wing, provocative and incompetent. In general, the post-war period was marked by disputes and debates in the cultural sector. Tensions arose between tradition and modernity, between elite and popular culture and between classical or more commercial and popular conceptions of culture, the latter inspired by the USA in particular.

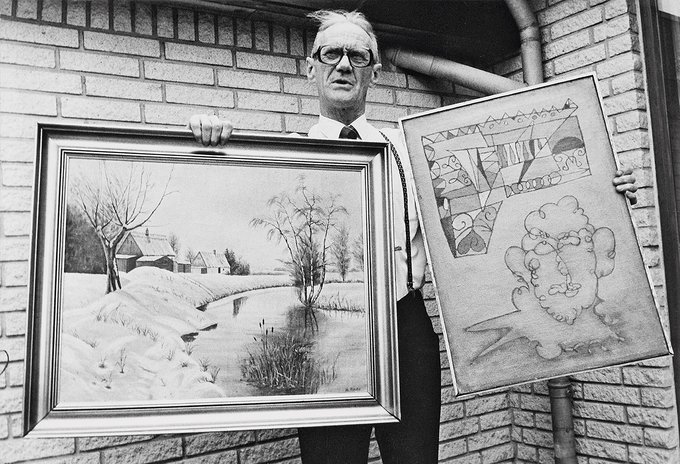

The opposition to the Danish Arts Foundation – and to 1960s cultural policy more broadly – was expressed in particular in a movement called ‘Rindalism’, named after one of the foundation’s strongest opponents, Peter Rindal. Rindal was a storekeeper from Kolding; he is pictured here with examples of a traditional and a modern abstract painting. The cultural debate of the 1960s rendered explicit a gap between the ‘people’ and the ‘elite’, which had political overtones. Rindal later became a member of the Progress Party (Fremskridtspartiet), which appointed him as the party’s representative in the Danish Arts Foundation in 1981. Photo: Viggo Landau, Ritzau Scanpix.

These conflicts were also reflected in literature and books, the market for which was now larger than ever before. There were three main reasons for this: the population was better educated; people had more disposable income; and, as an important part of post-war cultural and welfare policy, people across the country now had access to public or school libraries.

From the 1950s, it was free to borrow library books, and the desire to democratise culture led to a new law in 1964 stipulating that all municipalities should have a public library. This resulted in several newly built and modern libraries. Mobile libraries were introduced as an innovation in sparsely populated areas. The range of library material was expanded – though not without accompanying opposition and debate – to include more children’s and young adult literature, as well as music, comics and weekly magazines. The cultural function of the libraries could be seen in the borrowing figures: while each Dane borrowed an average of 3.5 books a year in 1945, this figure had risen to over fifteen books by 1973.

Print media

During the early decades of the twentieth century the four major parties – Venstre, the Social Democrats, the Conservatives and the Social Liberal Party – each had their own party press, including nationwide as well as local newspapers. In many towns and regions, newspapers were published with party support – and they were bought and read. The system came under pressure during the post-war period. Circulation figures began to decline, and people spoke of ‘the death of the newspaper’. Between 1945 and 1970, the number of newspapers halved, and competition for readers and advertising revenue often meant that only one local newspaper survived. This reflected changes in the political sphere, where the four-party system was also being phased out; the media landscape thus changed, as newspapers generally defended particular political views but also focused heavily on advertising and sales revenue. The sensationalist press, which attracted buyers with spectacular headlines in large fonts and lurid, sexual stories in text and image, gained ground and influenced large parts of the rest of the press.

Radio and television

The growth of radio in the inter-war period was consolidated in the postwar era. Statsradiofonien (the State Broadcasting Service) expanded and became the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (Danmarks Radio) in1959. From 2 October 1951, television programmes were broadcast,initially for one hour every other day to just two hundred viewers close to the broadcast transmitter in Copenhagen. The new medium came from the USA. In 1953, only three hundred and three households had a licence, as television sets were exorbitantly expensive and reception extremely volatile. However, within a few years, the television had become a common household item.

Eric Danielsen hosted the first TV-Avisen (TV News) on 15 October 1965 at 8pm from Radiohuset (the Radio House) in Copenhagen. Only 1% of all households in Denmark had a television in 1956, but this had risen to 38% in 1961, and in 1973 almost the whole population had access to one – initially black and white but also increasingly colour sets, which were introduced in 1967. The success of the television occurred at the expense of the cinema in particular, which since the turn of the century had largely enjoyed the exclusive right to disseminate culture and news in moving images. Photo: Hakon Nielsen, Ritzau Scanpix

The Danish Broadcasting Corporation had a monopoly on radio and television throughout the period, and there was only one television channel, despite competition from illegal pirate broadcasters and channels from neighbouring countries. The medium landscape was also marked by a movement away from a relatively elitist view of culture. Both radio and television included more popular content with entertainment, sport, quizzes and music (rock, beat and pop), just as children’s entertainment was given a completely new and strong position in its own right. This development was also accompanied by confrontations between the elite/classical and popular/commercial views of culture.

The television medium also heralded new forms of news coverage, not least when the opportunity to broadcast live via satellite arose during the 1960s. Events from the world’s hotspots came closer and shaped culture, society and politics, for example in connection with the youth rebellion and the Vietnam War. The visual world of television became part of a common imagination, nationally and internationally. The most spectacular example was the Cold War space race between the USA and the USSR in the 1960s, which culminated on 20 July 1969, when the USA landed the first men on the moon. The moon landing was transmitted to approximately 600 million viewers, around a fifth of the world’s population. For those who witnessed the event in real time, this transmission created new common iconic images and a new shared awareness of the Earth – the blue planet – and its place in the universe.

♦ Modernity, prosperity and rupture

By 1973, Denmark had become a wealthy and modern country. Technology had progressed considerably, making agriculture and industry more efficient – to such an extent that the country was now first and foremost a highly developed industrial nation. The welfare state had reached new heights and had become universal, with support available for all citizens from the cradle to the grave. Society had also become more equal, partly because of re-distributive policies and economic levelling, and partly because of increased educational and professional opportunities. The gap between rich and poor was thus smaller, and living standards had risen for the vast majority of the population.

Not everything was positive, however. Although Denmark was not involved in military conflicts in the post-war period, the Cold War came to affect politics, culture and society. The cycles of escalation, détente and the status quo formed a constant backdrop to the discussions and visions of the period, while at the same time instigating Denmark’s political, economic and military integration in the Western bloc with an unprecedented level of international obligation. Conflicts and wars in what was known at the time as the Third World, the superpowers’ arms race and the threat of a nuclear third world war also led to a general state of fear, unpredictability and uncertainty among the population and the decision-makers.

Whilst the many cultural and social shifts created social and economic mobility, they also led to tensions in the population and in politics. Polarisations developed between urban and rural, young and old, individual and community, left-wing and right-wing and the educated and the unskilled. In other words, new fractures and contrasts in the population and in politics made it difficult to reach consensus on major issues and social priorities. And new clouds were gathering on the horizon. The welfare state and the growing public sector gave rise to planning and management challenges and led to an increased tax burden, and the growing environmental movement highlighted the negative consequences of growth and the consumer society. In addition, early signs of economic imbalance began to appear, which were severely exacerbated when the oil crisis hit at the end of 1973. The golden age of the economy was on its way out, and it was followed, as we will see in the next chapter, by major political and cultural ruptures.