2. Denmark in the Nordic region, Europe and the Western bloc

Following the surrender of Germany and Japan in 1945, the world community faced the major task of re-establishing diplomatic and international co-operation, while avoiding the escalation of conflicts and aggressive nationalism. The depression of the 1930s and the Second World War, with its huge civilian and economic losses, were viewed as failures of international economic co-operation and political diplomacy. However, the post-war period soon became defined by new conflicts, and with the onset of the Cold War from 1946–1947 Denmark had to navigate a new context of bloc formations and international organisations. Denmark’s foreign and economic policy was to orient itself towards the West through membership of NATO and the European Community, and to establish tighter Nordic co-operation. Its foreign and security policy after 1945 was thus largely defined by its relations to these inter-governmental and supranational organisations.

The Cold War and new alliances

The period from 1914 to 1945 is sometimes seen as one continuous era of international conflict, culminating in the Second World War. ‘No more war’ was therefore the slogan for politicians and weary populations in the immediate post-war years. Hopes of peace were dashed, however, by ideological tensions and overlapping spheres of interest, particularly for the two countries that became major post-war powers: the USA and the USSR. These were ‘superpowers’, to use the new word coined to describe these global heavyweights, and thus even larger and more powerful than the traditional political and economic great powers like Britain, France and Germany, which had built up strong states, empires and alliances in the nineteenth century.

The four allied great powers had met during the Second World War to discuss spheres of interest and possible solutions. At the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944, Britain, France and the USA agreed on new international economic rules to try to avoid a return to the economic instability of the inter-war period, and at the Yalta Conference in February 1945 they were joined by the USSR to agree on geopolitical spheres of interest. In the immediate post-war years, efforts were made to build bridges between the Allies of the Second World War. The hope was that an organisation for effective inter-governmental collaboration could be founded in order to reduce conflict and prevent a new war, unlike the failed League of Nations of the inter-war period.

The United Nations (UN) was established on 24 October 1945. It was intended to be a collective security organisation, but dialogue and collaboration were disrupted in the face of growing antagonisms, aggressive military actions and mistrust between the allied Western powers and the communist USSR. The years 1946–1947 therefore marked the beginning of the Cold War.

In 1949, the North Atlantic Pact (from 1950 the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO) was set up as a defence alliance for the USA, Canada and ten western European countries, including Denmark. Following West Germany’s accession in 1955, NATO was countered by the Warsaw Pact, which united the USSR and the eastern European communist countries in a joint military alliance. At the same time Denmark had to navigate an increasing number of western European political and economic co-operative frameworks. These included the Organisation of European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), of which Denmark was a member 1948–1959; the Council of Europe, which Denmark joined at its inauguration in 1949; and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which Denmark joined at its inauguration in 1960, but left again in 1972. Finally, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Economic Community (EEC) and Euratom became the European Communities (EC) in 1967, and Denmark became a member in 1973 together with Britain and Ireland.

The four cornerstones of Danish foreign policy

The driving force behind much of the Social Democratic Party’s policy in the post-war era was the politician Per Hækkerup. He was foreign minister between 1962 and 1966, and published the book Danmarks Udenrigspolitik (Denmark’s Foreign Policy) in 1965, in which he presented Danish foreign policy from historical, geostrategic, military and political perspectives. According to his interpretation, Danish post-war foreign policy had four cornerstones: NATO, the United Nations (UN), Europe and the Nordic countries. While security was to be addressed through NATO and partly in the UN, foreign economic and trade policy was handled in the European and Nordic spheres, while the promotion of peace and other values took place in the UN and through Nordic co-operation. Through the various institutional frameworks linked to these four cornerstones, Danish foreign policy was cast in a new mould, representing a clear break with the tradition of neutrality and non-alignment that had guided Denmark during the First World War, the interwar period and the German occupation.

On 4 December 1962 the Danish Foreign Minister Per Hækkerup (middle) met with the US President John F. Kennedy (right) in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington. Also in attendance was the Danish Ambassador, K.G. Knuth-Winterfeldt. According to American archive material and Danish news reports, items on the agenda included the escalation of Cold War tensions during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, American–Danish co-operation over military installations in Greenland and a call for a stronger Danish financial commitment to NATO. Hækkerup mentioned the hope that Denmark would soon become a member of the EEC. A few days earlier he had met with UN Secretary-General U Thant. These international meetings epitomise Hækkerup’s analysis of the cornerstones of Danish foreign policy: integration in the Western bloc through co-operation on security and economy issues, while ideals of peace, broader international co-operation and support for developing countries were anchored in the UN. Photo: JFK Library

Neutral or allied?

Since 1864 Denmark had seen itself as a neutral country, in line with the other Nordic countries. Traditionally, Denmark’s biggest threat had been Germany, but after the collapse of Nazism it no longer posed the same urgent threat. The USSR, in contrast, soon came to be perceived as a superpower with potential interests in annexing Denmark in order to gain access to important strategic positions. It had become clear during the Second World War that the USSR had clear expansionary ambitions to subjugate regions and states in eastern and central Europe, and its sphere of interest turned out to be close to Denmark, as shown by the Soviet occupation of Bornholm in 1945–1946.

The challenges of neutrality, the experience of occupation and new threats were thus of decisive importance to Danish foreign policy after 1945. It became clear that, in a modern war situation, Denmark would be a vulnerable and poorly armed small state that would be difficult to defend against modern atomic weapons. But the country was also of considerable geopolitical and strategic importance, close to the new arenas of potential conflict. In the first official speeches and proclamations around the time of the liberation on 4–5 May 1945, Danish politicians and others claimed that Denmark was among the allied nations that had fought Nazi Germany, even though the country had in fact been occupied, and had negotiated and collaborated with the German occupying power. Denmark’s arguments for belonging to the ‘right side’ were that it had exercised ‘passive resistance’ towards the Germans, and that the resistance movement, the American presence in Greenland, the underground press and the rescue of the Jews in October 1943 were all proof that Denmark had long supported the Allied victors. Denmark was also quickly recognised as an ally by politically pragmatic Western powers, which became a prerequisite for being able to participate in many of the post-war plans, agreements and organisations.

Denmark joins the UN, 1945

Plans for a new international security organisation were put into action immediately after the German surrender. The founding charter of the United Nations (UN) was negotiated and completed between April and June 1945. On 26 June 1945, Denmark was one of the fifty-one countries that signed the charter in San Francisco. Denmark’s desire to be part of the UN was driven by a blend of security politics, pragmatism and idealism. The UN was seen as a vital security framework for a small state like Denmark, while membership also required that Denmark took on the obligations that followed, including the required military investment. For many politicians membership signalled that Danish neutrality was a thing of the past.

The UN Charter expressed grand idealistic ambitions, but conflicts and power struggles quickly emerged among the great powers. As a consequence the UN soon became partly paralysed as East–West tensions played out within the organisation. At the same time decolonization in Africa and Asia increased the number of new nations and hence UN members, which also transformed the UN into an arena for a North–South divide. Internationally and nationally, UN policy was therefore marked by clashes between ideals and realities. Denmark initially had a rather low-key approach towards the UN, and Danish crisis support was limited to humanitarian and medical aid, for example during the Korean War of 1950–1953.

With the Suez Crisis in 1956, a new Danish position started to emerge, which involved deploying UN soldiers as peacekeeping forces in collaboration with other Nordic countries. This represented a re-orientation towards greater international engagement within Danish security policy, foreign policy and ideology, which gained further momentum with the détente in Cold War relations that occurred from the 1960s. In step with this, the idealistic aspect of the UN gained a more prominent role and became the main feature of Danish security policy. It was also an expression of a new type of Nordic co-operation within an international context. Joint Nordic Blue Helmet forces took part in the UN’s first peacekeeping missions in Gaza (1956–1967), Congo (1960–1964) and Cyprus (1964–1994).

The North Atlantic Treaty, NATO and the turn to the West, 1949

Denmark’s UN policy was paralleled by its NATO policy, which was marked to a greater extent by military issues such as re-armament and conflicts between East and West. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, the old idea of enhanced Scandinavian military co-operation was revived based on the assumption that the old policy of neutrality was passé in the new world order, and that maintaining unarmed neutrality was unrealistic. Negotiations began in an effort to establish a Scandinavian defence alliance, but they stalled. Swedish politicians wanted a neutral defence alliance based on joint Scandinavian military capabilities, while the Norwegians wanted a Scandinavian alliance to be aligned to a wider Western defence framework. The Danish Social Democratic government stood somewhere in the middle, slightly inclined towards the policy of neutrality and thus to a strong Scandinavian solution.

When Norway and Denmark entered into the North Atlantic Treaty, the Scandinavian plans had already been shelved due to the three countries’ incompatible views. On 24 March 1949, after some hurried decisions, the Folketing decided to accept the formal invitation to enter into military collaboration with the USA, Canada and nine other western European countries. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was founded a few days later, on 4 April 1949, and quickly developed military significance through the creation of a joint military organisation, NATO, in connection with the Korean War of 1950–1953. An important part of the treaty was Article 5, the so-called ‘musketeer oath’ (‘one for all, all for one’), according to which member countries committed to mutual military assistance if one country was attacked. Article 5 was essential to Denmark’s decision to join the alliance, since it was seen as a guarantee that any Soviet invasion of Danish territory or attack on military installations would be met with a united response from NATO members.

Allied with reservations

Military facilities, airfields, bunkers and emergency response plans were established in Denmark under the NATO umbrella, and NATO exercises took place on Danish soil and in Danish waters. However, Denmark’s NATO membership was not without reservations, which led to several domestic political discussions and negotiations. Traditionally there were strong anti-militaristic positions in Danish politics, anchored in the Social Liberals (Det Radikale Venstre) and the Social Democratic Party, which played the largest role in government during the period. Despite the military alliance, a policy of neutrality was still viewed by many as preferable, were it not that pragmatic considerations and international political developments required Denmark to take a position.

The USA insisted that relinquishing sovereignty was an important part of NATO membership, for example in connection with establishing American bases on member states’ territory, but this presented a major and unfamiliar challenge to Danish foreign policy and was thus met with reluctance on the Danish side. It also represented a completely new way of thinking on the part of the USA, which had traditionally been relatively isolationist but now, in the nuclear age, developed a much more activist international policy. Many European countries, including Denmark, had difficulty adapting to this. From the 1950s, international and extraparliamentary movements also emerged, which mobilised opposition to atomic weapons and the growing defence budget, and thus influenced the debate on Danish foreign and defence politics. In the end Denmark evoked a ban on foreign bases and nuclear weapons on its territory.

In 1952, Turkey and Greece became NATO members. This gave the alliance new and important geostrategic and military opportunities in the Mediterranean, but it encountered resistance from other member countries – particularly Denmark and Norway – which did not wish to admit undemocratic states. The decision to admit West Germany into NATO in 1955 was not popular among the Danish population, for whom anti-German sentiment, memories of the occupation and opposition to German re-armament still loomed large. In contrast, the Danish government and military were in favour of West Germany joining the alliance as they thought it would strengthen Danish defence, while the risk that (West) Germany would once again develop in a military and aggressive direction would be eliminated through binding agreements.

Denmark’s membership of NATO was thus marked by a combination of an active policy to adapt to the new world order and the mind-set of a small state. As a NATO country, Denmark has therefore been described as ‘an ally with reservations’. NATO was seen as an insurance against the threat from the Eastern bloc, while the legacy from the inter-war period of the strong desire for neutrality was reflected in Denmark’s resistance to increasing military expenditure, and to foreign bases and nuclear weapons on its territory. The Danish defence budget rose at the beginning of the 1950s when the Cold War escalated, but it then fell to such a low level that the Social Democratic prime minister Jens Otto Krag received harsh American criticism of Danish caution during an official visit to the USA in 1964.

The foreign policy trump card: Greenland and the Thule Air Base

The Danish government’s somewhat hesitant willingness to participate fully in the military alliance was outweighed by what has been called the Greenland trump card. During the Second World War, the USA had established military bases in Greenland, which it was allowed to retain and expand according to the Greenland Defence Agreement signed by the Danish and US governments in 1951. In the nuclear age Greenland acquired further significance for US territorial defence. Immediately before the constitutional change of 1953, the Danish state carried out a forced relocation of twenty-seven Greenlandic hunting families. At extremely short notice, these families were told they had to move from Thule to the small hunting ground of Qaanaaq, approximately 150 km to the north, in order to make way for the US air base at Thule. Under the code name Operation Blue Jay, the Thule Air Base (from 2023 Pituffik Space Base), located in the far north and close to the USSR, became a central part of American nuclear defence. It was a bomber staging base, but also an increasingly vital early warning radar station in case of a Soviet nuclear attack.

Following a plane crash in 1968, it became known that part of the American Arctic defence included overflights by B-52 bombers armed with nuclear weapons. These planes were part of a global airborne alert programme which included permanent overflights of Greenland and constant visual contact with Thule, as a safety supplement to telecommunication with the base. The plane crash demonstrated the Danish double standard on nuclear weapons: no to nukes in Denmark, yes to them in Greenland. However, the Danish government seized on the crash as an opportunity to pressurise the American government into terminating the double standard, even though the latter was very critical of the Danish move. In 1969 both countries agreed on a supplement to the 1951 defence agreement which banned nuclear weapons in Greenland in peacetime. Archival studies made after the end of the Cold War have further shown that the Danish government knew about the presence of nuclear weapons on the American airbase at Thule from 1957, and accepted it through secret agreements.

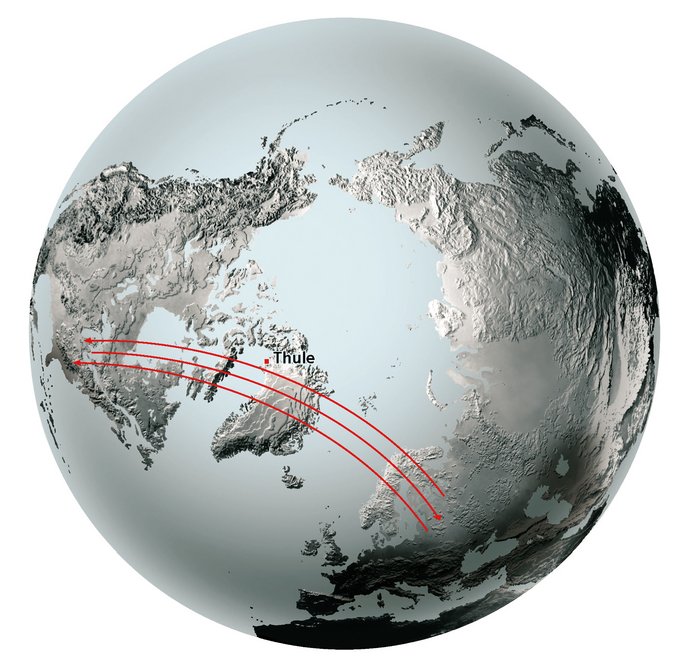

This slightly unfamiliar perspective on the northern hemisphere shows the importance of Greenland – and thus the Thule Air Base – for American security policy. The red lines depict possible missile routes for the two superpowers during the Cold War. Greenland was located midway between the strategically and politically important areas in the east of the USA (Washington and New York) and the west of the USSR (Moscow and Leningrad – present-day St Petersburg). Illustration: Hans Møller

Following a plane crash in 1968, it became known that part of the American Arctic defence included overflights by B-52 bombers armed with nuclear weapons. These planes were part of a global airborne alert programme which included permanent overflights of Greenland and constant visual contact with Thule, as a safety supplement to telecommunication with the base. The plane crash demonstrated the Danish double standard on nuclear weapons: no to nukes in Denmark, yes to them in Greenland. However, the Danish government seized on the crash as an opportunity to pressurise the American government into terminating the double standard, even though the latter was very critical of the Danish move. In 1969 both countries agreed on a supplement to the 1951 defence agreement which banned nuclear weapons in Greenland in peacetime. Archival studies made after the end of the Cold War have further shown that the Danish government knew about the presence of nuclear weapons on the American airbase at Thule from 1957, and accepted it through secret agreements.

European political and economic collaboration: visions and realities

The experiences of the world wars and the inter-war period created the background for new military co-operation, accompanied by efforts to establish closer political and economic co-operation in Europe. After decades of war, conflicts and economic crises, people believed that closer co-operation could prevent aggressive nationalism, promote democracy, boost the economy and increase European welfare. Joint European efforts in this regard were initially thwarted because of the Cold War, which divided Europe into the East and the West on either side of the Iron Curtain, but these intentions were soon to be realized in western Europe.

The idea of a political federation was abandoned, since France and Britain were against it. However, in 1949, ten western European states – including Denmark – formed the Council of Europe, an inter-governmental organisation focusing on political areas like democracy, human rights and the rule of law. European federalists were very disappointed at the limited ambitions of the Council of Europe, and so was France. The French government became increasingly worried about the plans of the USA and Britain to re-arm West Germany, which had been formed as a new state in 1949. Therefore, the French government presented two plans, the first for the creation of a Coal and Steel Community and the second for a European Defence Community. Both were aimed at securing control of West German rearmament and defence capabilities.

The Defence Community never materialised, but in 1952 Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany formed the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). This union established supranational collaboration and a common market for important economic and industrial areas; it was unprecedented in a European context, since it involved the transfer of national sovereignty and decision-making authority to joint institutions. For many years, national sovereignty had been a key part of the foreign and domestic policy of European countries. Even though countries in the ECSC only had to surrender their sovereignty in limited areas, the union represented a new type of co-operation, which over time came to be known as ‘European integration’. Danish governments followed the development of the ECSC very closely, but decided not to opt for membership because Britain and the other Scandinavian countries had no intentions of joining.

The EEC and the EC: European integration with Denmark on the sidelines

In 1957, following the establishment of the ECSC as a supranational institution, the Treaty of Rome was signed by the same six countries, leading to the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1958. The aim of the EEC was to promote economic integration, create a common market and establish a customs union among the members. Development was slow and marked by many obstacles and clashes between national interests, especially concerning the degree of national obligations and the supranational nature of the co-operation. In 1967, a merger brought together the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community to form the European Community (EC).

Growing European integration became an important part of Danish foreign and domestic policy in the 1950s and 1960s, even though Denmark did not become a member of the EC until 1973. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, there were hopes of establishing a common Nordic organisation for economic co-operation, similar to the defence co-operation ideas. These ambitions were never fully realised, though the founding of the Nordic Council (1952) paved the way for the Helsinki Treaty (1962) and the Nordic Council of Ministers (1971), establishing Nordic co-operation on economic issues, the labour market and cultural affairs.

In parallel with this Nordic development, Denmark began working to become a member of the EC, together with Britain, Ireland and Norway. Traditionally, Denmark had enjoyed extensive and important mutual trade with Britain, so joining the EC without Britain made little sense. At the same time, Denmark could not ignore the booming economic development (Wirtschaftswunder) of neighbouring West Germany, and thus became less reluctant to enter into economic co-operation with the former occupying power, which was now a growing export market. The EC’s common agricultural policy was particularly attractive for Denmark, since its price guarantees and subsidies promised new opportunities for one of the most important Danish export sectors.

The president of France, Charles de Gaulle, was fiercely opposed to British membership and vetoed the negotiations in 1963 and 1967, which also stalled Denmark’s application. Denmark was left in the uncomfortable position of holding a seat in what has been called ‘the European waiting room’. With de Gaulle’s departure in 1969, British membership became a real possibility, which led to Denmark starting accession negotiations with the EC in 1970.

Denmark’s entry into the EC, 1972–1973

If Denmark had been able to join the EC at the beginning of the 1960s, it would have been possible to do so without a referendum under the 1953 constitution, because 5/6 of the Folketing supported the decision at that time. The parliamentary situation was different in 1972, however, meaning that the proposal for Denmark to become a member of the EC had to be put to a referendum. This took place on 2 October 1972.

The debate leading up to the referendum was intense, and the opposing sides were keen to underline their differences. Opponents of EC membership spanned the entire political spectrum, but the main opposition came from the left, while the Social Democrats were divided on the issue. Arguments against joining the EC were primarily political-cultural, centring on the fear of losing national sovereignty. Arguments included scepticism towards joining a union dominated by Germany or even neo-Nazis, and by Catholics. The left wing and parts of the labour movement had concerns about letting foreigners into the labour market and feared the dominance of big capital. In general the fear was widespread that Denmark as a nation risked losing its status as a small, independent, harmonious and prosperous welfare state.

While the ‘no’ side used political arguments, the ‘yes’ side overwhelmingly employed economic arguments (higher pork prices, better market access and in general a stronger financial platform for funding the welfare state). In the referendum, 63.3% voted ‘yes’ and 36.7% voted ‘no’, meaning that, Denmark became a member of the European Community from 1 January 1973. A few days after the referendum, the French newspaper Le Monde described Denmark’s entry as ‘a marriage of convenience’, in which the ‘yes’ vote was interpreted as an expression of economic realism and consideration for Danish exports, rather than as a sign of Danish enthusiasm for the European political project. This analysis has proved to be relevant for much of Danish EC/EU policy since.

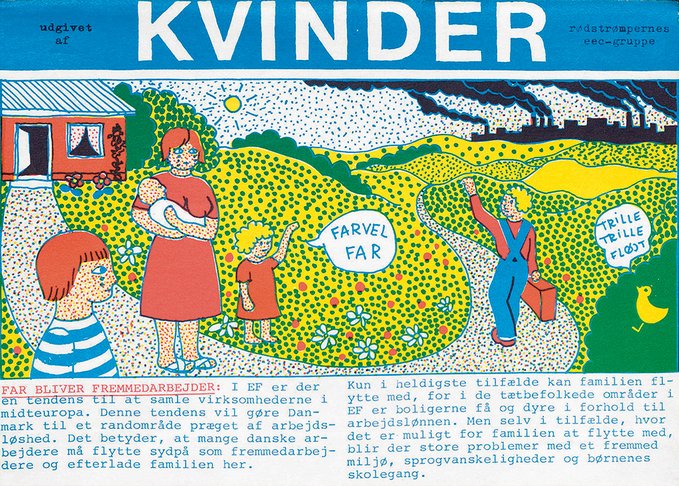

Both the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ sides put much effort into the referendum campaigns on Danish membership of the EC in October 1972. This picture shows a pamphlet issued by the Danish Red Stockings (Rødstrømperne) EC group, which argued that people should vote ‘no’ by emotively claiming that Danish families would be split up because fathers would be forced to take jobs as guest workers in German industry. The main message in the rest of the pamphlet was that, for the Danish population, EC membership would lead to lower incomes, higher prices and rising unemployment, as well as hampering the Danish welfare state in areas such as pensions, working conditions, equal pay and child care. Source: Women’s History Archive/Jette Szymanski 1971–1984 Miscellaneous, A3/3–4, Danish National Archives

Danish development aid as a field of foreign policy

One of the major international themes of the post-war era was the establishment of economic aid for developing countries. The number of developing countries grew rapidly in Africa, Asia and South America, as decolonisation and the right to self-determination meant that former colonial territories became independent – but often poor – states. Such countries were originally referred to as ‘underdeveloped countries’, later ‘developing countries’, and development aid programmes were launched that were seen as the wealthy countries’ compensation for colonial rule and an attempt to enhance global equality and security. However, the programmes were also motivated by the developed countries’ own economic interests in relation to the acquisition of raw materials, the need for labour and the expansion of export opportunities.

During the 1950s, the Danish state joined multilateral aid projects launched by the UN, the western European economic co-operation organisation OEEC (set up in 1948, from 1961 the OECD) and the World Bank (founded in 1945). Following the UN’s proclamation of the 1960s as a decade of development, in 1962 the Danish Folketing voted to establish bilateral development programmes with selected countries under the Danish International Development Agency (Danida), which became a department in the ministry of foreign affairs. The law on Denmark’s international development co-operation from 1971 established the organisational framework for aid. The emergence and development of Danish development aid with its focus on idealism, humanism and the fight against poverty can be seen as an extension and expansion of the commitment to the UN in Danish foreign policy. Together with Sweden and Norway, Denmark has been seen as a pioneer in this area, and aid became one of the guiding principles of Nordic international engagement. Denmark has also been criticised for failed projects, however, and for not fully understanding the cultural contexts of the recipient countries.