3. Economic growth and the welfare state

In many European countries, the Second World War left its mark in the form of bombed cities, damaged infrastructure and a large loss of life. In this regard, the impact on Denmark was extremely light, but the international economy was dominated by a world crisis for a number of years after 1945. This crisis meant that Danish wartime regulations of the economy and the supply of goods had to be phased out slowly. The rationing of luxury goods, gas and electricity, clothing and basic foods (such as bread and meat) was gradually phased out over the years leading up until 1952, when the final rationing stamps for coffee and sugar were abolished. Unemployment rose, there was a need for investment and modernisation, and, at the same time, there was a deficit in the balance of trade. The Danish economy became increasingly embedded in the international economy and thus affected by international economic conditions – to the extent that the importance of foreign trade rose from around 40% of GDP in 1948 to around 60% in 1970. Business and production patterns changed, and rapid economic growth – along with welfare policy – significantly changed the population’s opportunities and living conditions.

The Marshall Plan boosts the economy

One of the solutions to the economic challenges of the immediate postwar period came from outside Denmark. From 1948 to 1951, the USA ran the European Recovery Program, which was also called the ‘Marshall Plan’ after the incumbent minister of foreign affairs, George C. Marshall. Under the Marshall Plan, 13 billion US dollars were given to European countries in order to kickstart their economies following the Second World War. In principle, the offer was open to all European countries, but the Marshall Plan must also be seen as an American bloc-building initiative. For that reason the Soviet Union forced the countries of eastern Europe to decline the offer. It was thus only the countries of western Europe that received the economic boost, and at the same time sought and established further political and military co-operation with the USA as a partner. The Marshall Plan reflected a military and security policy that became central to the growth of America as a superpower: to ensure political and economic stability in western Europe in order to create a defensive wall against the USSR, communism and the Eastern bloc. More prosaically, the programme also aimed to support the domestic American economy, since the recipient countries had to use part of their aid to buy American raw materials, products and equipment.

There were misgivings about accepting the American offer across the entire political spectrum in Denmark. Politicians were concerned that accepting this aid could break with the ideals of unconditional Danish sovereignty and the right to self-determination, which continued to prevail in Danish foreign policy. Nevertheless, in April 1948, the Folketing voted to accept American aid; it was primarily economic arguments that led to the decision. Participation in the Marshall Plan was thus one of the first manifestations of Denmark’s affiliation with the Western bloc during the Cold War. Through the aid programme, the Danish economy received an injection of approximately 300 million dollars (approximately 4 billion dollars in 2023 values), which was given in the form of grants, currency support and to a lesser extent loans based on a so-called ‘long-term economic programme’ presented by the Danish government and approved by the US Marshall administration. The programme was particularly focused on developing manufacturing industry and making agriculture more efficient. The aid solved several of the immediate bottleneck problems in the energy and industrial sectors. It had a lasting effect for Denmark – and for other participating countries – because, as a condition, the USA demanded more European trade and trade liberalisation, as well as macroeconomic planning and co-ordination of economic policies in the recipient countries.

Social engineers

Receiving Marshall aid was conditional on the Danish government preparing long-term economic plans. This discipline became increasingly important in the economic and political visions of the post-war era, which were characterised by the objectives of planning, optimization and progress. Economic and social regulation was implemented not only due to American demands; it also had historical, theoretical and political motivations. The experience of the war economy – as well as state interventions in the economy during the inter-war period and economic theories such as Keynesianism – had made clear the extent to which governments, politicians and civil servants could act as social engineers to regulate crisis conditions, currency values, the balance of trade and consumer patterns. If such regulation made sense in times of shortage, it could presumably also be used in times of economic progress to steer the population’s behaviour and the state’s priorities in a particular direction, by constructing and implementing social models that were both economically viable and influential in improving the population’s health, welfare and employment. This approach to the state and the population broke with the traditional liberalist conception of society. It was therefore the Social Democrats in particular who first advocated the social model, along with methods that became central for the state administration and regulation of key economic indicators.

The economic boom takes hold

At the end of the 1950s, the Danish economy became part of the postwar international economic boom, as the international financial markets began to function again. In the 1960s in particular, there was unprecedented economic growth. In Denmark, this upswing occurred a little later than in other countries. Denmark encountered challenges resulting from the combination of an industrial sector that was underdeveloped compared with many other Western countries, and an agricultural sector that was losing its economic status and importance. These challenges were met by investing heavily in industrialisation and efficiency, especially in the manufacturing industries. After some delay the Western economic boom began to affect virtually all aspects of the Danish economy. GDP and productivity more than doubled, and imports and exports rose, stimulated by the post-war international trends towards more free trade and trade agreements rather than protectionism and custom barriers. Unemployment fell to under 2% – and thus to a level known as ‘natural unemployment’, since it was primarily accounted for by minor structural adjustments, job changes and the geographical relocation of people and workplaces.

Economic development had major demographic implications. In 1945, the population was almost equally divided between cities with over 100,000 inhabitants, other urban areas and rural districts. In 1970, only one fifth of the population lived in rural areas; the smaller islands were rapidly depopulated; and migration from the countryside to the towns and cities made it difficult for villages to maintain their shops, workplaces and schools.

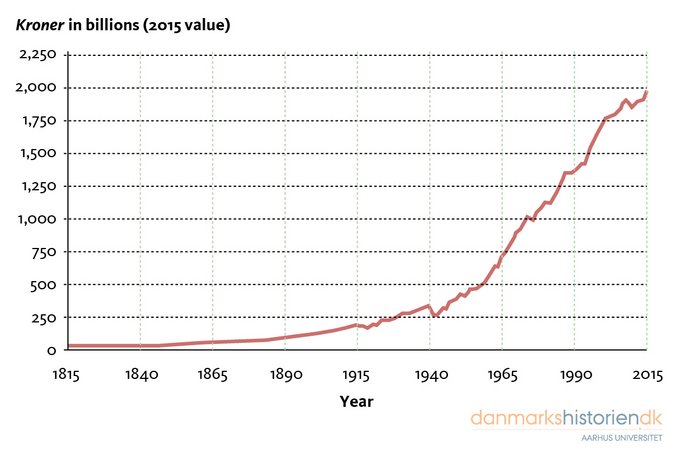

This graph shows Denmark’s GDP over two hundred years: from 1815 until 2015. GDP rose significantly in the 1960s. Since the Second World War, GDP has generally continued to rise, except for slight decreases in connection with the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s and the financial crisis of 2007–2009. © danmarkshistorien.dk, based on figures from Statistics Denmark

The development of the welfare state

Post-war economic policy was linked to existing ideas about creating a different and better society with greater welfare and equality, which over time became known as the ‘welfare state’ (velfærdsstaten). The term started to appear in politics and the public sphere in the late 1940s, and by the mid-1950s it was frequently used in political discourse. However, there was no clear idea or well-established definition of what a welfare state actually was. While the word ‘welfare’ (velfærd) has an inherently positive ring, the welfare state was by no means automatically perceived as positive. In the 1950s and 1960s, it was used as a derogatory term by some right-wing politicians, who thought the growing welfare state would create a kind of paternalistic society or ‘nanny state’. Parts of the left wing believed that it overly standardised the population and passivized its will to resist and rebel.

Those in favour of the welfare state connected their arguments to earlier Danish legislation, creating a narrative of continuity from the social laws on old age support and health insurance from 1891/1892 to the social legislation of the inter-war period. The post-war expansion of the welfare state was described as a logical development of something particularly Danish, or even particularly Nordic. Politicians and social scientists referred to the northern European welfare states as having similar characteristics, because all the Nordic countries implemented welfare systems at the same time and often under the leadership of Social Democratic parties, in which all citizens had the same right to services such as free education and health care. The particularly Nordic qualities of these welfare states were that benefits were universal – in other words they were based on citizen rights – and that welfare was financed by progressive taxation and not insurance, as was the case in other European countries. The implementation of the state pension in 1965, as the first universal benefit and right, was a Danish milestone, since all citizens over sixty-seven were entitled to it without having to apply or have their needs assessed.

State-employed home carer (husmoderafløser) Kirstine Vilhelmine Thomsen at work in a family with a newborn child in the early 1950s. The law on housewife replacement (husmoderafløsning) was adopted in 1949. It built on an initiative from 1941 which made it possible for underprivileged families to receive help. With this law, the scheme became one of the first welfare policy measures that was partly universally based, since everyone now had the right to receive short-term, publicly funded domestic help when necessary in connection with, for example, ill health or maternity leave – though the scheme was regulated according to income and the number of children in a family. Photo: Historical Archive Hjørring

The zenith of the welfare state in the 1960s

‘Make good times better’ was the Social Democrats’ slogan for the 1960 Folketing elections. In many ways, the 1960s were the zenith of the welfare state. It was a decade of high economic growth, which made it possible to expand the welfare state rapidly and comprehensively. After the conflicts and disagreements of the 1950s, there was now a much wider political consensus that Denmark was and should continue to be a welfare state. Perhaps inevitably, there were differences of opinion regarding objectives and resources, but welfare policy became a central concept in Danish politics, along with the idea that it was possible to regulate people’s choices, priorities and behaviour. Welfare policy was thus seen both as a tool to realise political visions of a better society and as an economically rational instrument to regulate the economy. In other words, it became a model in which population policy, social policy, value-based policy and economic policy were united.

In the 1960s, welfare policy resulted in particular in the establishment of many more child care institutions, care homes for the elderly and hospitals. The education system was expanded, and several benefits were introduced to alleviate the disadvantages associated with illness, incapacity for work and disability. Social care became far more extensive, and in 1971 the state abolished the insurance-based health scheme; free health care was introduced in 1973.

Public expenditure, CPR numbers and tax reforms

Developing a welfare state was expensive. Public spending more than tripled between 1945 and 1973, even when adjusted for inflation; in 1948 it had made up 12% of GDP, and by 1973, this figure had risen to 21.6%. In 1962, the Economic Council (Det Økonomiske Råd) was set up as an expert panel to monitor economic development and make recommendations for macroeconomic co-ordination, including welfare state spending. Later, the government initiated the Perspective Plans I and II, which, in 1971 and 1974 respectively, sought to predict public sector development and assess the consequences in order to facilitate coordination and inform sustainable budgets. However, the basis for these plans collapsed when the economic crisis hit in 1973–1974.

The development of the welfare state also led to fundamental reforms in the economic relationship between state and citizen. In order to implement its new policies on housing, social security, health and culture, the government needed to increase the tax burden. In 1970, the ‘tax at source’ system for income tax was introduced. Whereas people had previously paid their tax in arrears, it was now deducted directly from the individual’s salary. In order for this new taxation system to work, an effective method of personal registration and identification was required. The Central Person Register (CPR) was established in 1968, under which every citizen was assigned a ten-digit personal identification number (a CPR number) from birth. As machine data handling, punch card systems and computers proliferated, the CPR system gradually replaced the registration systems of the past, which were based on extended families and households. The CPR system was a personal and individualised means of managing every citizen’s contact with the public sector in areas such as health care, education, social security, military service and voting rights. At the same time, it became a central part of the state’s registration and control of its citizens. This development unfolded in earnest in connection with digitisation and the internet from the 1980s onwards.

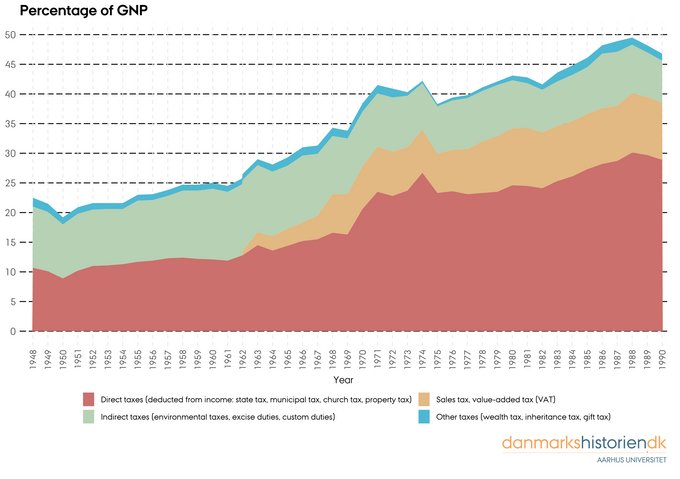

Taxes were also introduced on the purchase and sale of goods and services. In 1962, a sales tax of 9% (oms) was introduced for wholesale. In 1967, this was replaced by a value-added tax of 10% (moms), which was applied at the retail level. Overall, the tax burden – consisting of direct tax, indirect tax, sales tax, excise duty, taxes on cigarettes and alcohol and environmental tax – rose from 23.7% in 1948 to 40.3% in 1973.

This graph shows the distribution of taxes as a percentage of GDP, 1948–1990. As shown, the overall tax burden increased significantly in the post-war era, simultaneously with the expansion of the welfare state. Direct taxes and value-added taxes (VAT) showed the largest increase. The rate of increase was highest in the 1960s, then flattened off in the 1970s before climbing again in the 1980s. © danmarkshistorien.dk, based on figures from Statistics Denmark

Municipal reform in 1970 and the organisation of the welfare state

A central element in economic and administrative development was the municipal reform, which came into force on 1 April 1970. The existing 1,098 municipalities were diminished in number and the distinction between rural and urban municipalities was abolished. There were now two tiers of local government: fourteen counties (amtskommuner) and two hundred and seventy-five municipalities (kommuner). Areas that had once been the responsibility of the state (psychiatry, social care and education) were now delegated to county level, and the municipalities were given more responsibilities regarding children and young people, as well as business and the environment.

The background to the municipal reform of 1970 was the need to develop the welfare state and to find more land for industrial districts in larger urban areas. It was not possible for smaller units to carry out such tasks, as they demanded a degree of centralisation and specialization that could only be realised economically and practically by larger units. In addition, many small rural municipalities were effectively ‘tax havens’ for their closest market town, drawing on its services and infrastructure. This became a problem as migration from rural to urban areas continued. In addition, the rural parish council varied considerably across the country, and there were many examples of misuses of power and differences in the ways in which individual cases were dealt with. The municipal reform thus helped to pave the way for greater uniformity in public administration and less arbitrariness in the implementation of the welfare state.

Citizens in the welfare state

The development of a comprehensive and expanded welfare policy in post-war Denmark affected all Danish citizens significantly – ‘from the cradle to the grave’, as it was said. The state gained an unprecedented amount of control over and knowledge of the lives of its people, at the same time as more and more areas became part of welfare policy. This applied in particular to people who were outside the workforce: children, young people, the sick, the unemployed, the disabled, students and the elderly. At the beginning of the post-war period, most of these people were dependent on their spouses, parents or other relatives. As a result of the increasing number of welfare benefits, these groups became entitled to transfer payments such as pensions, unemployment benefit, rehabilitation benefit, income support, child benefit, student grants, early retirement benefit and sickness benefit. Receiving benefits in these life situations was nothing new, but the significant difference was that these benefits were now universal and rights-based, and thus much less dependent on discretion or subject to stigmatisation. The concept of the ‘deserving needy’ was thus phased out in social and welfare policy. At the same time, social spending by the state, counties and municipalities increased dramatically. This development marked a departure from the family as the primary support unit and followed the trend of increasing individualisation. People became less financially dependent on their families and social mobility grew, so that more people from unskilled and poor backgrounds had the opportunity to pursue an education, settle elsewhere and choose another way of life than that prescribed by traditions, norms and the family.

The agricultural sector: mechanization and decreasing importance

The agricultural sector was characterised by simultaneous development and decline. On the one hand, work processes were modernized and industrialised; on the other, agriculture became less important (macro)economically and as an identity marker for large sections of the population, who found employment in other sectors. Modernisation had started gradually in the 1930s with electrification, which took off in earnest after the Second World War, aided by the Marshall Plan and American equipment and machinery. By setting up their own generators on site, farmers could use powered equipment to perform jobs that had previously demanded several hours of labour from men, women and children. Cows were milked by milking machines, and animals could graze freely in the field behind electric fences, without the need for tethers or shepherds.

Motorisation – which was again funded with start-up aid from the USA – meant that agricultural machinery became widespread. For almost all farmers, the small tractor became an all-round tool for ploughing, harrowing, sowing, fertilising and harvesting, and larger machines such as forage harvesters and combine harvesters gradually came into use. Animals were no longer required to pull farming equipment, and improved efficiency meant that agriculture now required fewer resources and less manpower. The development towards more intensive farming continued with the enhanced use of chemical fertilisers, the avoidance of fallow land and larger yields on both crops and livestock.

Artificial insemination and the targeted breeding of cattle improved milk yields and meat quality. Over the period, the average annual milk yield of a dairy cow increased from approximately 2,000 to 5,000 litres. Battery farming and the intensive rearing of chickens led to the establishment of a poultry industry. Finally, through targeted breeding, farmers were able to produce pigs that grew faster, had more meat and less fat, and had a longer rib cage with extra ribs and vertebrae. The animals could thus provide more cutlets and more bacon, the latter especially for export.

Although the growth rate of industry was much larger than that of agriculture, and despite the decline in agricultural employment, the agricultural sector continued to be very important to the Danish economy due to its very high export quota. This was also a main reason why Danish governments of the 1960s were so eager to see Denmark become a member of the EC and its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Growth in the industrial and service sectors

Mechanisation and increased efficiency – attained among other ways through the scientific organisation of production processes – meant that productivity in Danish industry increased significantly in the post-war era. Major investments were made in machinery and automated work processes, as well as the development of transport links, while higher levels of consumption and more exports increased demand for industrial products. This was reflected in the fact that, around 1962–1963, the industrial sector replaced the agricultural sector as the largest contributor to GDP. It also meant that the workforce grew and that workplaces acquired a completely new character and structure. At the beginning of the post-war period, around a quarter of the 2 million-strong workforce worked in the primary industries (agriculture, fishing and raw material extraction). In 1972, this figure had fallen to below 10%. Parallel to this, there were more wage earners and fewer self-employed workers.

The secondary sector (industry and construction) and the tertiary sector (trade, transport and services) experienced growth during the same period. Growth was particularly strong in the tertiary service trades and the public sector. While only 7% of the workforce was employed in the public sector in 1948, approximately 20% – equivalent to half a million people – was in 1973, reflecting the expansion of the health care and social sectors. There were more doctors, nurses, child and youth workers, teachers, social workers, home carers and social and health care assistants. Many of these new workers were women, who began to join these workforces especially from the mid-1960s.

The Welfare State

Watch this film in which Anne Sørensen talks about the welfare state. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about nine minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.