6. The occupation, 1940–1945

The final part of the world war era in Danish history was defined by the German occupation during the Second World War. These ‘five evil years’, which is how the occupation period from 9 April 1940 to 4 May 1945 is often described, had an enormous impact on post-war national and democratic identity. Seen in the context of the world war era as a whole, however, the occupation appears differently. In some respects, it marked the culmination of three decades of extremes and upheavals. In others, it was an important but limited period of exception that, in the long run, helped to strengthen developments that had already been set in motion decades before. This applied in particular to democratic and popular identity, as well as to state regulation of the economy.

The world war and occupation, 1940–1945

Political efforts to maintain Denmark’s favourable neutral relationship with Germany required special consideration during the Nazi period. As early as the mid-1930s, the Danish government had asked the Danish press to refrain from criticising Germany and Nazism. Although the government took initiatives to strengthen the defence of Danish neutrality, it became obvious that Denmark would only be able to provide symbolic resistance to a German invasion. So when the Germans offered Denmark a reciprocal non-aggression pact in the spring of 1939, nearly all the parties in the Rigsdag agreed that this should be signed. The only exception was the Communist Party, which continued to call for a joint anti-fascist alliance – a ‘popular front’ – of the working-class parties and moderate forces among other classes. However, the anti-fascism of the communists was soon revoked. When the Soviet Union entered into a non-aggression pact with Germany in August 1939 (the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact), the Danish Communist Party loyally followed the Soviet line, despite reluctance both inside and outside the party.

The Spanish civil war of 1936–1939 and the German annexation of neighbouring territories demonstrated that more than a diplomatic agreement was required to deter Hitler from attacking as soon as it was opportune. On 9 April 1940, German troops invaded Denmark as part of a strategically important attempt to conquer Norway. After brief battles along the southern Jutland border, the Danish government agreed ‘under protest to manage the country according to the occupation that had taken place’, as announced by Minister of Foreign Affairs Peter Munch on behalf of the Danish government.

Initially, the Germans preferred to accommodate Danish wishes to preserve Danish political institutions, to let the 1920 Danish–German border remain and to continue officially to recognise Denmark as an independent neutral state. On the day after the German occupation, Stauning formed the first national unity government by incorporating three ministers from each of the large right-of-centre parties, namely Venstre and the Conservative People’s Party. This laid the groundwork for political collaboration and a distinct shift to the right in Danish politics. While the government continued to be led by the Social Democrats, during the occupation the leading Social Democrats felt pressured to accept policies that prioritised agriculture and industry to the detriment of working-class wages and living standards. In this way, it was possible to maintain the central organisations of the labour movement, but in the longer term it also paved the way for reinforced Communist challenges to the traditional predominance of the Social Democrats within the labour movement.

The Occupation on April 9th 1940

Watch this film in which Niels Wium Olesen discusses what the nearly battle-free occupation meant for the policy of collaboration and the relationship with the Germans. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about ten minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Support for Germany

Collaboration between the political parties was accompanied by a gradual increase in collaboration with the occupying power. After the rapid succession of German victories in Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg and France, in July 1940 the Danish government was reformed. It now included some ministers without party affiliation, such as businessman Gunnar Larsen, while Peter Munch was replaced as minister of foreign affairs by the non-partisan diplomat Erik Scavenius. This marked small but important steps in the direction of the ‘apolitical’ power of experts that businesspeople in the so-called ‘Højgaard Circle’ had recently proposed instead of parliamentary democracy. At the same time, it represented a more pronounced German-friendly course. The new government’s accession statement, written by Scavenius, expressed admiration for the German victories and spoke of a ‘new time’ that called for ‘necessary and mutual, active collaboration with greater Germany’.

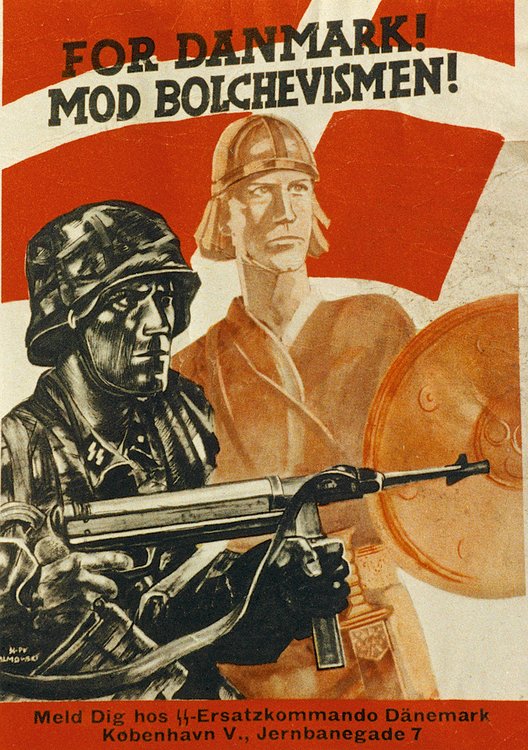

German Soldier, Danish Viking. Recruitment poster for the Free Corps Denmark for the fight against Bolshevism in the east. People joined the corps for a range of reasons, including financial incentives, the desire for adventure and ideological conviction. The soldiers fought for the Germans against the Soviet Union in harsh battles on the eastern front, and many died. After the occupation, Danish volunteer soldiers were viewed as traitors and many were prosecuted. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance, National Museum of Denmark

After the German attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Danish government agreed to the establishment of the Free Corps Denmark, which included 3,000 Danish volunteer soldiers sent to fight on the eastern front under German command. At Germany’s request, the Danish Communist Party was also banned on 22 August of the same year, and the police detained hundreds of its most prominent members – many more than the Germans had stipulated. This represented a government-sanctioned violation of the constitutional freedom to form associations; the arrests even included two members of the Folketing who should have ordinarily enjoyed parliamentary immunity. In addition to the convenient disposal of political opponents, however, the intention was paradoxically to save as much of the constitution as possible by conspicuously obliging the occupying power. In November 1941, Denmark continued along this path by joining the German Anti-Comintern Pact, an international anti-communist alliance.

Resistance

The stricter German requirements and the government’s policy of collaboration nurtured opposition to the Germans and the occupation. From 1942, resistance groups began to emerge. These groups were rooted in strongly national conservative forces on the one hand, and communist circles on the other. The latter were now free of the inhibitory German–Soviet pact from 1939–1941 and combined the national struggle for freedom with workers’ social demands and support for the Soviet Union. Representatives from both wings of the resistance movement met with each other and with representatives of the intermediate political spectrum in the organisation Frit Danmark (Free Denmark) and, from 1943, Danmarks Frihedsraad (The Danish Freedom Council). In the final two years of the occupation the second organization co-ordinated the efforts of the Danish resistance groups and increasingly came to resemble an alternative Danish government.

The resistance groups agitated against the occupying power and carried out acts of sabotage against military targets and Danish industrial companies that supplied the Germans. The government, which after Stauning’s death in May 1942 was led by fellow party member Vilhelm Buhl and afterwards – at the Germans’ request – by Erik Scavenius, condemned these resistance efforts and appealed to the population not to support them. At around the same time as Scavenius’ appointment, Hitler installed the SS officer Werner Best as the civilian administrator in Denmark, and General Hermann von Hanneken was sent to the country as military commander. German hegemony was becoming increasingly more pronounced.

The occupying power still sought to win the goodwill of the people, among other things by allowing municipal and parliamentary elections in the spring of 1943. In the parliamentary elections on 23 April, the parties of the national unity government won over 93% of the votes. This indicated widespread support for the policy. Even during the occupation, the Danish Nazi party did not win more than 2.1% of all votes.

The policy of collaboration and redistribution

The German occupation meant that Denmark could no longer send exports to what was traditionally seen as its most important market, the UK. This severely affected Danish agriculture and parts of Danish industry, and some industrial companies were forced to shut down. On the other hand, the occupying power showed itself willing to purchase a much larger share of agricultural production than previously, and to supply Denmark with coal and other necessities. New earning opportunities also arose, especially for agriculture, fisheries and the industrial companies that could produce for the Germans.

Just like during the First World War, people had to deal with shortages, inflation, social polarisation and redistribution. The housing shortage got drastically worse, and poverty-related diseases such as tuberculosis and scabies resurfaced. Unlike during the First World War, the government was considerably less reluctant to intervene in the economy with comprehensive rationing and price regulation of basic foodstuffs. What was lacking was no longer hard currency but goods, so the Board of Goods Supply (Direktoratet for Vareforsyning) stepped in instead of the Exchange Control Office.

The regulation of the economy prevented extreme suffering and inflation, but many still had to make do with less. Unemployment rose again during the first months of the occupation, but it fell considerably during the war compared with rates in the 1930s, partly because of the combination of declining productivity and new sales opportunities in specific sectors of industry, and partly because Danish workers were recruited for jobs in Germany.

When urban workers found themselves out of work, this was also due to the Social Democrats’ willingness to find common ground with the other collaboration parties – in particular Venstre, who did not hesitate to demand a policy that benefitted wealthier farmers. As early as the summer of 1940, wages were reduced by 20% by law, and the cost-of-living adjustment – that is, compensation for price increases – was limited. Strikes were forbidden, and mediation in labour disputes was placed in the hands of a new Work and Conciliation Board (Arbejds- og Forligsnævn), which was dominated by industrial figures and employers, and which lacked notable influence from the workers’ organisations. The top of the trade union movement, under the leadership of the chair of the Federation of Unions, Laurits Hansen, loyally followed this line of negotiation. Hansen even once negotiated with the Germans about the possibility of co-ordinating the Danish trade union movement with the German Nazi Labour Front. This was a sign of the acute weakening of the labour movement during the occupation.

National humiliation, the general economic shortage, and the worsening conditions for workers during the occupation created widespread outrage against the industrial companies who profited from the occupation and supported the German war effort, often through the use of forced labour. They were referred to as ‘collaborationists’ (værnemagere) and were widely condemned. The farmers, on the other hand, were not the subject of hatred for the same reasons, presumably because their trade with the Germans was less conspicuous and because, compared with other countries, Denmark managed to retain relatively high levels of supplies during the war. This was considerably advantageous for many Danes – in the midst of all the decline.

The collapse of the policy of co-operation

From 1942/1943, rumours about the difficulties the German army was facing on the eastern front and in North Africa, as well as the Fascist government’s defeat in Italy, began to shake the widespread expectation of long-term German supremacy. In most of occupied Europe, as in Denmark, resistance groups grew and became more active, and increased employment in the same period improved the workers’ real wages and strengthened their fighting spirit.

In August 1943, major strikes broke out in a number of larger Danish provincial towns, clearly directed against the occupying power. The civilian administrator Werner Best demanded that the Danish authorities respond harshly with bans on strike action and demonstrations, night curfews and the death penalty for sabotage. When the government refused to meet these demands, it meant the end of the policy of cooperation. The government, king and parliament ceased functioning. Municipal councils remained in operation, but central administrative functions were now performed by the administrative leaders of the individual ministries. The occupying power now administered the rest of the country directly. The German authorities disarmed the Danish army and navy – despite resistance from the navy, in particular – and introduced a period of martial law lasting several weeks. The Gestapo came to Denmark in order to fight the resistance movement. One year later a massive strike and protest movement in Copenhagen – called a ‘people’s strike’, since many employers and independent shop-owners supported and participated in the movement – was met by a declaration of martial law and savage repression. Following those events, the Danish police force was dissolved, and a quarter of its officers were deported to concentration camps in Germany. In its place, the new rulers established the so-called Hilfspolizei (auxiliary police force). The HIPOs, as the new police officers were commonly known, were Danish Nazis and Nazi sympathisers. Their brutal behaviour soon turned them into hated everyday symbols of Nazi oppression.

As a part of tougher German rule and its efforts to exterminate the Jewish population internationally, it was decided in 1943 that Danish Jews should also be captured and deported to German concentration camps, as had previously happened in other countries. The Germans managed to apprehend 500 Jewish people, but warnings had been leaked in advance, so approximately 7,000 Jews were able to flee, mainly to Sweden, in time to escape deportation.

In the summer of 1944, a so-called ‘people’s strike’ (folkestrejke) broke out in Copenhagen. It marked the biggest confrontation between the German army and the Danish population/resistance movement, which organised work strikes and erected street barricades. The Germans responded by introducing martial law and shooting randomly in the streets. Here, a woman and two men lie dead on a street corner in the workers’ district of Nørrebro, a long-standing stronghold of left-wing politics. Approximately one hundred people died and six hundred were injured during the people’s strike. Photo: The Museum of Danish Resistance, National Museum of Denmark

Liberation, 1945

In the final months of the war, confrontations between the resistance movement and the occupying power intensified. In response to the resistance fighters’ acts of sabotage and the assassination of informants, the occupying power began to blow up prominent Danish buildings and to carry out retaliatory killings of Danes. Large parts of the resistance movement became increasingly militarised in preparation for the fight for Denmark’s liberation, while the movement’s leading circles reached out to work with former politicians of co-operation in order to ensure that post-war Denmark could be rebuilt in continuation of the moderate, parliamentary-democratic course it was following before the conflict.

The decisive battles in the final weeks of the war were fought elsewhere in Europe, so Denmark’s liberation was simply announced on the radio on the evening of 4 May 1945. The occupation was over for Denmark, with the exception of Bornholm, which came under Soviet rule and remained so for nearly a year following the Red Army’s victory over German occupation forces on the island.

In the summer of 1945 Denmark was marked by enthusiasm for Danishness and democracy. But it was also experiencing shortages and internal opposition. Urban workers in particular had suffered economically and socially. This provoked new major strikes in the initial months after the war and widespread dissatisfaction with the Social Democrats, who had helped to worsen conditions for the workers.

However, with their election programme Denmark of the Future in the summer of 1945, leading Social Democrats had already laid down plans for a modern welfare state that was to be built up in continuation of the state regulation of the world war era. During the Cold War and the subsequent long-term economic upswing, the Social Democrats regained much of the support they had lost and managed to make their welfare policy the focal point of Denmark after the two world wars.

♦ From the world war to the post-war era

As in other parts of the world, unrest and uncertain future prospects were central to Danish historical reality between 1914 and 1945. Nevertheless, the traditional classes, parties and cultural currents largely succeeded in averting the kinds of major political ruptures that characterised the development of so many other European countries at the time. Against the background of the policy of neutrality during the two world wars, the large, old, class-based political parties generally managed to maintain solid and broad support among the population for a political strategy that was based on conflicting class interests and oppositions between rural and urban while, at crucial points, also reconciling these interests through compromise-based reforms.

This dominant line of development was highly significant for the country during the world war era and in the decades following. It is true that many of the trends present in Denmark in the period were actually global phenomena: the increasing importance of commodity production, industrialisation, urbanisation, the exchange of people and goods over larger distances, economic crises, perceptions of rupture and non-contemporaneity. But Denmark’s relative peace and important social and political compromises helped to sustain parliamentary democracy as a political convergence point, even during times when the government was under pressure or dissolved, such as during the Easter Crisis and in the final years of the occupation. The same factors helped to ensure the survival of the market economy – though it became increasingly state regulated. Although the crises in Denmark were real and felt by the population, the relatively peaceful way in which the country developed enabled the economy to progress throughout most of the period. The increasing level of financial regulation and redistribution helped to give much larger sections of the population access to citizenship – even if real social and economic equality was still a long way off. It was thus possible to strengthen both the general sense of belonging to a nation and the perception of Denmark’s history as a continuous development towards equality, democracy and welfare.

All these factors formed the basis for Denmark’s further development in the post-war decades.