3. Ruptures within foreign and domestic politics

Just as they had been during the first French Revolution and again in the mid-nineteenth century, domestic political developments were closely connected to foreign policy and influenced by transnational social and economic tensions. Despite this, the national political institutions remained the focal point of the conflicts of the time. In Denmark, these national institutions were primarily the two chambers of Parliament (Rigsdagen): the Lower House (Folketinget) and the Upper House (Landstinget).

Parties between classes and people

The period after the First World War was characterised by a myriad of new political currents, many of them at the extremes of the political spectrum. Nevertheless, throughout the period, Danish politics was dominated by four large parties rooted in clear political, ideological and social divisions. In this respect, the large parties helped to institutionalise the class society. At the same time, however, all four parties also increasingly presented themselves as people’s parties, rather than pure class parties. They often showed a willingness to co-operate and compromise with each other – not least to safeguard existing society and its institutions from political extremism.

The Conservative People’s Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) was founded in 1915 but had its roots in Højre (‘right’), the old party of the bourgeoisie and the landed interests. The new party continued to campaign for Højre’s priority issue – strong national defence – but it was more committed to democracy and appealed to broader sections of the population, initially to the self-employed but later also to white-collar workers. This new course secured the support of between 15% and 20% of voters throughout the period and gave new life to conservatism as an ideological standpoint in Denmark, though the party remained outside the government for the entire period and also experienced fierce internal conflicts.

Venstre (‘left’), the party for the better-off farmers (gårdmænd), was ideologically founded on liberalism and campaigned for free trade and reduced state spending. It was historically anchored in the nineteenth-century struggle for democracy against the old Højre and the landed aristocracy, but it had moved to the right in the face of the labour and smallholders’ movement, and collaborated more closely with the Conservative People’s Party than it had with Højre. There were still significant differences of opinion between the two parties, however, most often rooted in the social-economic conflicts between town and country, and between industry and agriculture. These differences came to mark Venstre’s periods in government in the years 1920–1924 and 1926–1929, when the party still held around a third of the seats in the Folketing. During the 1930s and the Second World War, this share fell to a fifth of all seats.

The Social Liberal party (Det Radikale Venstre) allied itself with the smallholders (husmænd). After several decades of debate about smallholders’ rights, it was now finally possible to build up a smallholder movement, which distanced itself from the farmer-dominated agricultural associations. Within the Social Liberals, the smallholders aligned themselves with certain groups of urban intellectuals and intellectual workers, not least schoolteachers. Rather than a narrow class policy, the party pursued a democratic and anti-militarist line. Throughout its long period in government during the First World War, it had to balance this line with military considerations and cross-party collaboration. In the inter-war period, the party lost some of its voter support and saw a reduction from nearly a quarter of all Folketing seats following the election in 1918 to only a tenth of all seats from the middle of the 1920s. From 1929 onwards, the party became a junior partner in the Social Democratic governments under Thorvald Stauning, while parts of the Social Liberals looked to the right out of a desire to do away with bloc politics.

The Social Democratic Party continued to expand until the German occupation in 1940; it was the leading government party from 1929 and into the occupation period. The party was rooted in the urban working class. Since its foundation in 1871, it had committed itself to immediate reforms in the interests of the workers and long-term socialist goals. But even the Social Democratic Party increasingly presented itself as a people’s party with broad appeal. There should be ‘room for us all’, as the poet Oskar Hansen wrote in his song Danmark for Folket (Denmark for the People) in 1934 – a tribute to the party’s new programme of the same name. In this way, the Social Democrats marked their distance from the new, extreme currents of the inter-war period on both the left and the right, which operated with more exclusive conceptions of ‘the people’.

The First World War and Danish neutrality

When the European Great War broke out in August 1914 between two opposing alliances – the Entente Powers (France, Britain and Russia) and the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) – each with their own set of allies in other countries, it was feared that Denmark would be drawn into the military conflict. If there were an extended naval war between Germany and Britain, it was likely that the Danish waters would become an important arena of conflict, especially since Denmark controlled the entrance to the Baltic Sea. Both sides suspected the other of wanting to exploit Denmark in the war.

Despite long-standing disputes among Danish politicians on the question of defence, there was general agreement at the outbreak of the First World War that Denmark should do its utmost to avoid being drawn into the conflict. If Denmark joined the war, there was a danger that it would be destroyed as an independent nation and subordinated to one of the other foreign powers, most likely Germany.

There was therefore widespread agreement on the Danish side that Denmark should seek to maintain its neutral position, together with the other Scandinavian countries, while also demonstrating a will to safeguard this neutrality. Under the leadership of C.Th. Zahle, the Social Liberal government stretched the principles of neutrality as far as possible in a pro-German direction. This was most clearly apparent when the government – with hesitant support from the opposition – complied with German demands to lay naval mines in Danish waters against an incoming fleet, most probably the British navy. The Social Liberal government had to bend its traditional pacifism considerably when it agreed to mobilise its large security force (sikringsstyrke) of 50,000 troops to man the national fortifications. These had been extended with the Tune Stronghold, a series of fortifications from Køge Bay to Roskilde Fjord designed to protect the capital.

The threat of being drawn into the war became real on several occasions, but Denmark managed to avoid entering the conflict. This was due not only to the Danish policy of neutrality but also to the warring parties’ expectation of a quick war and an imminent victory for their own side, which proved to be greatly misjudged. The conflict became deadlocked in trench warfare. While Germany began an unrestricted submarine war in 1917, which cost the lives of considerable numbers of Danish sailors and brought the threat against Denmark to its zenith, there were never any actual acts of war on Danish territory.

The foreign policy of neutrality ensured Denmark’s continued independence and secured the lives of its inhabitants, but it also had significant economic and social consequences, which will be explored later in this chapter.

The League of Nations

After the end of the war in 1918, Denmark entered the inter-governmental League of Nations, the primary mission of which was to ensure peace and mutual understanding between peoples. The prevailing opinion of the time was that the massive mutual destruction of the First World War should never be repeated. However, for Denmark and its policy of neutrality, the main disadvantage of joining the League of Nations was that it was primarily an organisation for the victorious warring parties, and one of its main objectives was to secure sanctions against non-League states. This put Denmark in a potentially difficult situation with Germany, which was excluded from the League at the start. Along with other Scandinavian countries, Denmark therefore favoured less binding security policy co-operation and was able to ease the demands for small and vulnerable countries to take part in sanctions.

When Germany was allowed to join the League of Nations in 1926, many of the high expectations with which the League was founded had already been disappointed. At the beginning of the 1930s, the Danish government worked through the League for European disarmament, and in 1935 it also joined the League’s attempt to punish fascist Italy for the invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). Both efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, reflecting the circumstances of an organisation that, in the 1930s, could only look on impotently while Nazi Germany in particular prepared for war. The pressure of this development led Denmark – and many other states – to take a more passive role in the League in the second half of the 1930s.

Constitutional reform, 1915

The most significant change in Danish domestic politics during the First World War was the new constitution. This was adopted on 5 June 1915 – the day was chosen for its symbolic significance as the sixty-sixth anniversary of the adoption of the first constitution – but only came into force after a Folketing election on 22 April 1918, having been postponed several times due to the extraordinary circumstances of war. The new constitution gave women and servants of both sexes the right to vote in parliamentary elections, and the voting age for Folketing elections was lowered from thirty to twenty-five. At the same time, it removed privileged Landsting voting rights for the 1,000 largest taxpayers – in other words a small group of the country’s wealthiest people – originally introduced in the constitution of 1866. The electoral system was also reformed: from simple majority elections in single-member constituencies to a form of proportional representation, which more adequately reflected the increased influence of the urban population in the country as a whole.

The cross-party collaboration of the First World War thus paved the way for a compromise, which went a long way towards realising the demands for democratisation made by the women’s movement and the labour movement before 1914. The new constitution amounted to a universal acknowledgement of the reality of modern mass society and the democratic values of the new age.

However, the anti-democratic Højre politicians obtained political concessions in return for their acceptance of the new constitution. Not only was the Landsting maintained as a conservative bastion, but also the voting age for its elections was increased from thirty to thirty-five, even though the voting age for Folketing elections had been reduced. As compensation for the loss of privileged voting rights and the system of royal appointment under the 1866 constitution, the political continuity – and thus conservative dominance – of the Landsting was ensured by an ingenious system requiring that a quarter of the new Landsting members be appointed by the outgoing Landsting, and not by the people directly. The parliamentary principle – that a government may not have a majority against it in the Lower House – had been a generally accepted norm since the formation of the first Venstre government in 1901, but the 1915 constitution failed to enshrine it.

Finally, the entire constitutional system was safeguarded by making it more difficult than before to implement new constitutional amendments. After 1915, amendments had to be put to a referendum and be supported by at least 45% of eligible voters. It was this rule that prevented the Social Democratic government’s long-awaited proposal for a new constitution from being adopted a quarter of a century later, in 1939. The proposed reform was intended to introduce the same voting rights for the Landsting as the Folketing, and to lower the overall voting age. Whilst it achieved a solid majority of the votes cast, turnout was too low for the proposal to be adopted. This was because the Conservative People’s Party was divided over the proposal, while Venstre was against it and campaigned to minimise turnout. The next decisive step in the democratisation of the constitution thus had to wait until it was renewed in 1953, during a period of unequivocal enthusiasm for democracy.

Revolutions and bloc politics

The democratisation of Danish political institutions was achieved through compromise and reform, against the background of a new wave of revolutions. The commotion of war shook the European social order, and old regimes were overthrown in many countries. This was particularly the case in Russia, where the Tsar was ousted in the early spring of 1917 and a communist government came to power half a year later. In 1918–1919 there were similar upheavals in Germany, following the military defeat and fall of the empire, with the emergence of soldiers’ and workers’ councils.

There were echoes of both revolutions in Danish politics. The Danish government intensified its military presence at the Danish–German border and tightened its grip on the small, young organisations of the extreme left. A syndicalist opposition demanding a general strike had begun to challenge the more moderate wing of the Danish labour movement, even before the war. Now the Syndicalists were joined by radical young social democrats who wanted to break with the parent party. In the months surrounding the end of the war in 1918, this new extreme left was behind various spectacular actions and large demonstrations, which sought to drive the criticism of social deprivation in the direction of a revolutionary break with capitalism. From 1919, these political forces were brought together in the Communist Party of Denmark (Danmarks Kommunistiske Parti). This remained a relatively small and marginalised party, however, until the German occupation of 1940–1945, when it won wider respect for its role in the resistance movement, even though its political and cultural role was never as central as that of its French and Italian sister parties, for example.

The Battle at Grønttorvet on 13 November 1918 was one of several major clashes in Copenhagen between law enforcement authorities and the revolutionary left wing in the wake of the world war, revolutions abroad and domestic poverty. Angry demonstrators stopped a tram in Frederiksborggade, and the young Syndicalist Johannes Sperling jumped onto the tram roof, red flag in hand, to address the crowd. Before he could utter a word, however, the police removed him and confiscated the flag. Peace was restored after three days of clashes between the police and demonstrators. Photo: Danish Police Museum

There was also unrest at the other end of the political spectrum. Spurred on by the fear of Russian Bolshevism and widespread strikes, in 1920 Danish industrialists established an organisation for strike-breakers, Samfundshjælpen (Social Aid), which was designed to assist workplaces affected by labour disputes, if the authorities requested such assistance. Samfundshjælpen quickly attracted 7,000 members. A similar organisation, Landbrugets frivillige Arbejdskraft (Voluntary Agricultural Labour), was established to safeguard agricultural exports in the event of labour disputes in the transport sector. Throughout the 1920s, a plethora of extremist right-wing currents emerged in protest against the labour movement, socialism and the dissolution of old values and hierarchies. Some of these furthered existing right-wing standpoints, and others developed new, radical forms of conservatism with strong national or religious overtones, often explicitly inspired by Mussolini’s Italian fascism. These new forms of conservatism found a voice in newspapers such as Jyllands-Posten and Nationaltidende, as well as countless smaller journals. However, the extreme right wing of the 1920s did not achieve a unified voice or organisation.

On the whole, political extremism in Denmark remained relatively limited in comparison with the rapidly growing and more militant movements on both political wings south of the border. This was partly due to longstanding traditions of seeking compromise and consensus, but it was also because Denmark had been able to stay out of the First World War and thus avoided its worst consequences, including severe impoverishment, social collapse and massive war trauma.

The Easter Crisis, 1920

There was one crucial moment when it seemed that revolution was close, even without the involvement of the radical political movements described above. This was the Easter Crisis of late March 1920, when Christian X dissolved the Social Liberal government. He was spurred on by a group of influential, politically conservative and fiercely national businessmen, led by the founder of the East Asiatic Company H.N. Andersen, shipping magnate A.P. Møller and brewer Vagn Jacobsen. In its place, the king installed a caretaker government under the leadership of his lawyer, Otto Liebe. This was dominated by representatives of business rather than of the parliamentary parties. The change took place against the majority of the Folketing and in violation of the parliamentary principle.

For the dissolved Social Liberal government, and, to a greater extent, its Social Democratic supporters, this event amounted not only to a step backwards toward J.B.S. Estrup’s authoritarian right-wing rule of the late nineteenth century; its attack on democracy was also akin to those being carried out by movements abroad at the same time. The king’s dissolution of the government took place only a few days after the Kapp–Lüttwitz coup in Germany, during which right-wing forces had attempted to overthrow the newly established Weimar Republic. The German coup was halted by a general strike, and the Danish Social Democrats threatened a similar move against what they considered to be a coup d’état by the king.

The background to the dispute was complex, but a central factor was the Social Liberal government’s acceptance of the results of the referendum on the future Danish–German border. The German majority vote in Flensburg intensified the right-wing struggle on this issue and against political democratisation in general. This coincided with increasing tensions between the labour movement and the employers over the renegotiation of collective agreements. There was support for the caretaker government from the leader of Venstre, who saw a short-term interest in holding the new election under the old election law, since this was particularly beneficial for his rural party base. The Easter Crisis was thus not merely a government crisis. It was also a test of strength between left and right, between supporters of parliamentarianism and their opponents, and between trade unions and employers. Faced with intensified criticism of the monarchy as well as the prospect of a general strike, however, the king and some of his allies soon began to waver. After five days, a settlement was negotiated between the king and the parliamentarian forces, during which the Social Democratic party leader Thorvald Stauning in particular showed his skills in achieving compromise through negotiation. A new caretaker government was appointed and given the task of convening the Rigsdag, finalising the new election law and conducting a parliamentary election.

This solution led the Social Democrats and the Federation of Trade Unions (De Samvirkende Fagforbund) to call off the general strike. The closest thing to an anti-democratic coup d’état in inter-war Denmark had been averted – and so had the prospect of radical pro-democratic street politics on a mass scale. By threatening a general strike, the Social Democratic leaders had shown themselves to be radical enough to defuse the revolutionary left. And by reconciling with the forces to their right, they had also shown their willingness to pursue pragmatic reformism. This tactical agility contributed decisively to strengthening the party’s position in society as a whole. However, it did not prevent continued tensions in political institutions and the labour market throughout the 1920s.

Neergaard, Madsen-Mygdal and the Venstre government of the 1920s

Danish politics in the 1920s was dominated by Venstre governments, first under Niels Neergaard in 1920–1924 and then led by Thomas Madsen-Mygdal in 1926–1929. While these politicians represented the same party, the same social values and the same ideological position, their opinions were worlds apart. Neergaard was from a clerical family; he was educated as a historian and had an extensive authorship behind him. At almost seventy years old, he was a competent and generally respected prime minister. Madsen-Mygdal was twenty-two years younger and from a farming family; he was educated first as a schoolteacher and then as an agricultural consultant. As chairman of the Agricultural Council (Landbrugsraadet) from 1918, he advocated for agricultural interests and a principled economic liberalism. He was appointed minister of agriculture in the Neergaard government without previous parliamentary experience, and later became prime minister. Throughout, he was consistently in favour of free market forces and against the labour movement and the public sector.

Madsen-Mygdal’s position was reflected in his actions. During his time in government, there was strong pressure on workers’ conditions, with wage reductions and layoffs in the public sector. Construction on the Little Belt bridge between Jutland and Fyn was postponed, and the already modest benefits available for the unemployed were cut drastically, while unemployment reached more than 25% among workers with social insurance. The tax cuts that followed primarily benefitted the wealthy landowners at the expense of the urban and rural poor.

This rigidity became the Venstre government’s Achilles’ heel. The redistribution of resources from poor workers to employers and wealthy farmers provoked an outrage that helped strengthen the Social Democrats. Venstre’s course also ran counter to several of the key policies of the Conservative People’s Party, such as respect for the civil service, consideration of the special interests of Danish industry and the desire to increase the defence budget.

The situation ended during the Finance Act negotiations in 1929, when the new Conservative People’s Party leader, thirty-five-year-old John Christmas Møller, pulled the rug from under the Madsen-Mygdal government’s austerity measures. This put an end to a decade of Venstre dominance, which, with the benefit of many decades’ hindsight, can be seen as a swan song for the older nineteenth-century tradition of economic liberalism.

The Stauning era

The 1930s was the decade of the Social Democrats. The uncontested leader of the party in this period was Thorvald Stauning, the country’s first leading political figure from a working-class background. Stauning was born in 1873 and trained as a cigar sorter, but he soon proved to be a skilled and pragmatic organizer in the trade union movement and party. As a product of the labour movement’s belief in progress and daily battles over wages and working conditions, Stauning as a politician was also the opposite of dogmatists like Madsen-Mygdal, or the type of socialist who had eyes only for distant future objectives. At the age of thirty-seven, Stauning became leader of the Social Democrat Party, a position he retained for three decades alongside his work in the Folketing and successive governments.

During the First World War, he was minister without portfolio in the Zahle government. The fact that the Social Democrats accepted his participation in the government was itself a sign that the party was developing in a pragmatic direction and distancing itself from the old doctrine that it needed to command a majority before entering government, so that it could complete the transition to a socialist society. From 1924 to 1926, Stauning led the first Social Democratic minority government, which raised right-wing fears of a ‘working-class regime’. Equally symbolic was the appointment of the first female member of government in modern Danish history: historian Nina Bang, who became minister of education. In practice, however, this government was moderate and weak, both in its parliamentary position and in the face of economic unrest and strikes, which ultimately brought it down.

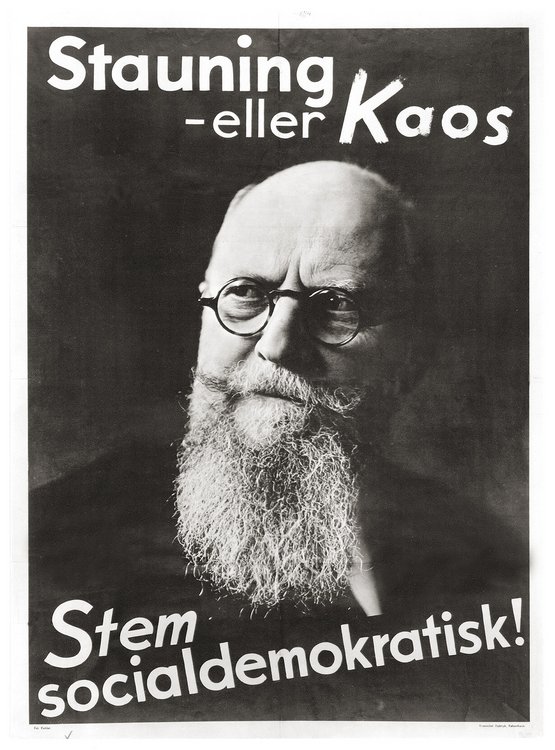

But Stauning got his revenge. As head of the Social Democratic–Social Liberal coalition government from 1929 until 1940, and later as leader of the cross-party national unity government during the German occupation and until his death, he gradually achieved the status of a national father figure. Under his leadership, the party and its political influence grew to new heights, from holding just over a quarter of the seats in the Folketing in 1918 to almost half in 1935, when the party campaigned under the slogan ‘Stauning or chaos’. Only his difficult position as a leading figure in the early phase of the national unity government during the German occupation could tarnish his long-term reputation.

‘Stauning or chaos’: election poster for the Social Democrat Party from 1935. In this election, the party achieved its best result to date, securing a 46% majority. By promoting a distinctive political personality rather than a party, which was atypical for Denmark at that time, the poster managed to give a reassuring, paternal feel to the Social Democrats’ populist image and centrist politics. Photo: © Kehlet, The Danish Museum og Photography, The Royal Danish Library

Challenges from the authoritarian right

The Nazis’ seizure of power in Germany in 1933 marked a significant defeat for the young European democracies’ struggle for survival. It was also a threat to Denmark’s overall security, and indeed to the entire modern enlightenment project. The rise of Nazism was part of a widespread tendency for authoritarian right-wing regimes to replace the new democracies in Central and Eastern Europe. And just like fascist leader Benito Mussolini in 1920s Italy, Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in 1930s Austria, Marshall Józef Piłsudski in Poland and many others, Hitler’s government began by suppressing the socialist labour movement. He then persecuted the Jewish population with ever-increasing fervour, based on an extreme so-called ‘Aryan’ racial doctrine.

Socialists, Jews, artists and intellectuals fled Germany, with some of them seeking refuge in Denmark. The official line of the Danish public authorities and politicians was that these people were a threat to state expenditure and, in the case of political refugees, a possible strain on Denmark’s relationship with Germany. Many of the refugees ended up moving on to other parts of the world. In the meantime, they had to seek assistance from non-governmental aid committees, each with its own area of responsibility, in particular the social-democratic Matteotti committee, the communist Røde Hjælp (Red Aid) and the Committee of 4 May 1933, affiliated with the Jewish community in Denmark.

Denmark sought to maintain a neutral yet accommodating relationship with the German state, even when this policy came under pressure. Hitler began to re-arm Germany, which violated the terms of the First World War peace treaty, and he laid claim to larger territories – initially neighbouring regions with large German-speaking populations.

The rise of the anti-democratic right wing in Central and Southern Europe also gave renewed impetus to the extreme right in Denmark. The Danish Nazi party (The National Socialist Workers’ Party of Denmark, or DNSAP), under the leadership of the medic Frits Clausen, sought to place itself in the slipstream of the German model while emphasising Danish nationalism. With the exception of Southern Jutland, however – where parts of the German minority backed Nazism – support for the Danish Nazi party was hesitant and limited. It was not until 1939 that the DNSAP managed to achieve representation (three seats) in the Folketing, while the veterinarian Jens Møller was elected as the representative of the so-called Schleswig Party. This was the rival Nazi party, which presented itself as the North Schleswig branch of the German NSDAP, and which, unlike Clausen’s party, wanted to revise the Danish–German border in Germany’s favour.

Another right-wing party was Danish Unity (Dansk Samling), which was more firmly anchored in domestic affairs. Dansk Samling was founded in 1936 by right-wing circles in the folk high school movement and based on its leader Arne Sørensen’s idea of a national ‘third way’, as an alternative to socialism and liberalism. It never became a large party, but it stood out by clearly distancing itself from the German occupation in 1940. Through its involvement in the resistance movement, it gained prestige and was briefly represented in the Folketing in the first election after liberation. After this, its role was very limited.

Other new right-wing movements had a more solid base. At one point, extreme right-wing tendencies were embraced by the Conservative People’s Party and in particular the Young Conservatives (Konservativ Ungdom). In the early 1930s this group began purposefully to recruit among the crisis-hit urban working-class youth, who could otherwise have formed the basis of socialist youth organisations. In this way, these groups followed the paths paved by Italian fascists and German Nazis. The most striking was the uniformed corps of the Young Conservatives who often came to blows with ordinary passers-by, or similarly uniformed squads of communist and left-wing social-democratic youth. Towards the middle of the 1930s, however, more moderate forces succeeded in counteracting these political currents of the street, partly by implementing a ban on uniforms and partly by actions taken by the leaders of the social-democratic and conservative youth organisations gradually to marginalise the more militant wings.

Uniformed Young Conservatives march outside the main train station in Copenhagen, shortly before the uniform ban on 12 April 1933. The inter-war period became a time of marches, demonstrations and intense battles over political symbols in the streets of Danish towns and cities, inspired by militant political movements abroad. There were also frequent physical clashes between activist forces from the right and left. Photo: Ritzau Scanpix

Knud Bach and the Agricultural Association

A much more significant force on the political right emerged among the farmers, who were hit particularly hard by the economic crisis of the 1930s. The Agricultural Association (Landbrugernes Sammenslutning, or LS) was a massive social protest movement founded in 1930 with Knud Bach, a charismatic farmer from Jutland, as its leading figure. Politically, socio-historically and culturally, Bach can be seen as the counterpart to Stauning. Bach was an enterprising and class-conscious farmer’s son, and the family business at Røngegård, near Viborg, expanded considerably under his leadership. For symbolic and practical reasons he also made Røngegård the home of the Agricultural Association.

Bach and his movement demanded the immediate alleviation of the farmers’ economic difficulties. His own vision of society was rather vaguely defined, but his rhetoric was fierce and directed against ‘the system’: the urban population, the labour movement and modern democracy. His movement became the focus for ideas about national and Christian revival. It challenged the democratic and economic liberalism of the old farmers’ party Venstre, whose dominant figures, along with the old agricultural organisations, distanced themselves from the new right-wing extremism. Ultimately, a small group of Folketing members who were sympathetic to the cause of the Agricultural Association left Venstre and founded the Free People’s Party (Det Frie Folkeparti), which later became the Farmers’ Party (Bondepartiet). This new right-wing conservative party gained five seats in the Folketing election in 1939.

Bach and the Agricultural Association showed strong support for Nazi Germany in the early phase of the occupation, and thus ensured favourable sales for Danish farmers on the German market. But this support for the Nazis also removed much of the basis for Bach’s protest movement, and after the liberation of Denmark it earned him a harsh prison sentence. After suffering a brain haemorrhage, he was pardoned and allowed to end his days at home at Røngegård in 1948. A memorial stone was later erected at Røngegård to pay tribute to ‘a bold and honest man / who fought for his threatened class’. The problematic political context in which he fought for his cause was thus repressed.