2. The consolidation of the nation state in the shadow of the world wars

The loss of Norway in 1814 and the duchies in 1864 left Denmark as an amputated nation state at the beginning of the twentieth century, with politicians and citizens alike gradually getting used to conceiving of their country as a small state. But one issue remained unresolved, namely Southern Jutland.

The reunification of 1920

During the First World War, the whole of Schleswig between the Rivers Kongeå and Eider was part of the German empire. Germany’s defeat in the First World War, the dissolution of the empire in 1918, and the victors’ desire for a smaller Germany created new opportunities to connect the Danish-minded areas of Schleswig to Denmark. Advocates of the Danish cause south of the border led the campaign, and the government of the Radikale Venstre (Social Liberal) Party in Copenhagen, led by Prime Minister C.Th. Zahle, supported the cause, albeit with a more cautious approach. The leading politicians wanted to put an end to border disputes, not pave the way for new ones by imposing a border so far south that it left a large German minority in Danish territory.

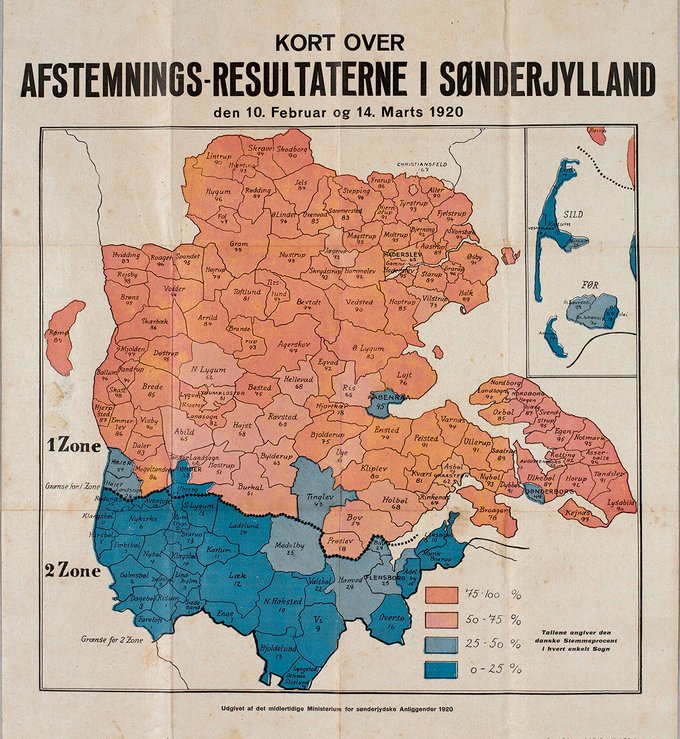

In February and March 1920, referendums took place in the so-called first and second zones of Schleswig, corresponding to northern and central Schleswig respectively, including the city of Flensburg. The third zone – the German-dominated southern part of Schleswig around the city of Schleswig – was of no interest from a Danish point of view.

In the northern zone, a solid majority of 75% voted for reunification with Denmark. However, in the central zone, an even larger majority voted to maintain a connection to Germany. Even in the city of Flensburg, proponents of the unification could only muster just under a third of the votes. The defeat in Flensburg led the right-wing forces in both Flensburg and the Danish state to accuse the Zahle government of having failed the cause. This paved the way for one of the biggest political crises of the twentieth century in Denmark, the Easter Crisis (Påskekrisen), which is discussed in more detail below.

Within the first zone, there also proved to be majorities identifying as German in several cities, including Sønderborg, Aabenraa, Tinglev, Tønder and Højer. The German side therefore argued that the new border should not follow the zone boundaries, but instead should be drawn along the so-called ‘Tiedje line’ (named after the German politician Johannes Tiedje), that is, north of Højer, Tønder, Kongsbjerg and Tinglev. Had the Danish government accepted this, it would have exacerbated its already tense relationship with frustrated Danish national forces both north and south of the border. Ultimately, therefore, the nation state of Denmark had to accommodate a not insignificant German minority after all, just as there continued to be a Danish minority south of the border.

Map showing the percentages of pro-Danish votes in the 1920 referendums. Because the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that the results in each zone had to be calculated collectively, the blue parishes with a German majority in zone one ended up belonging to Denmark. The results of the referendums formed the basis for the current Danish–German border. The map was published by Det Midlertidige Ministerium for Sønderjyske Anliggender (The Temporary Ministry for Southern Jutland Affairs) in 1920. Photo: Archive at the Danish Central Library for South Schleswig

Throughout the entire inter-war period, the German minority worked to ensure that northern Schleswig would again become German. When the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, it was expected that the German state would put its political weight behind hopes to revise the border in Germany’s favour. This did not happen, but even so, it was only in 1955 that the 1920 border was finally recognised by the new German government. With the border revision in 1920, the geographical scope of the nation state of Denmark was shaped for at least the next hundred years. Members of the new nation state gradually got used to associating the concept of ‘Sønderjylland’ (Southern Jutland) with the incorporated northern Schleswig territories, even though that concept had previously referred to the whole of Schleswig. However, relationships to other parts of the realm continued to be revised.

Throughout the entire inter-war period, the German minority worked to ensure that northern Schleswig would again become German. When the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, it was expected that the German state would put its political weight behind hopes to revise the border in Germany’s favour. This did not happen, but even so, it was only in 1955 that the 1920 border was finally recognised by the new German government. With the border revision in 1920, the geographical scope of the nation state of Denmark was shaped for at least the next hundred years. Members of the new nation state gradually got used to associating the concept of ‘Sønderjylland’ (Southern Jutland) with the incorporated northern Schleswig territories, even though that concept had previously referred to the whole of Schleswig. However, relationships to other parts of the realm continued to be revised.

The sale of the Danish West Indies in 1917

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Danish colonies and dependencies were the final relics of the larger realm that Denmark had once been. But Danish colonialism was being phased out. Most importantly, the Danish state sold its colonial dependencies in the Danish West Indies – the islands of St Croix, St Thomas and St John – to the USA in 1917. By 1848, slavery had been abolished, after which the islands had begun to make a financial loss. In the early twentieth century, they were also politically sensitive. Conservative forces in Denmark were proud of the ‘jewel in the Danish crown’, as the Danish West Indies were called. But even after the abolition of slavery, the working and living conditions for the majority black population on the islands were miserable. Social unrest and independence movements arose, led by the islands’ burgeoning labour movement. This aroused sympathy from both liberal forces and socialists in Denmark.

The decisive factor in the decision to sell, however, was that the islands occupied a militarily strategic position at the mouth of the Panama Canal. On the eve of its entry into the First World War, the USA offered to buy the islands for 25 million dollars. This was an extremely attractive offer for the Danish state, since it corresponded to approximately half of the annual state budget.

Nevertheless, the sale of the Danish West Indies sparked fierce debate, not least because Danish national pride was still wounded following the defeat of 1864. The question of whether to sell was therefore put to a referendum – in Denmark, not in the islands themselves. 64% of the votes cast supported the sale, but the referendum also showed that, despite the lucrative offer, a significant minority preferred to keep Denmark as a colonial power.

The forgotten workers. Women and men under the searing sun on the island of St Croix, c. 1900. Following a referendum in Denmark, the island was sold to the USA (along with Denmark’s other dependencies in the West Indies) in 1917. In contrast to the population of Southern Jutland, the population of the Danish West Indies was not given a say in the matter. Photo: National Museum of Denmark

Calls for change in the North Atlantic colonies

In addition to the sale of the West Indian colonies came the news of the secession of approximately 90,000 Icelanders from Denmark. Iceland had long had the status of a Danish dependency with a certain degree of self-governance, but it had fought for greater independence for decades. After lengthy negotiations, in 1918 the Icelandic and Danish parliaments agreed to recognise Iceland as an independent state, albeit in a personal union under the same monarch for the first twenty-five years. This agreement was suspended during the Second World War, when the connection between Denmark and the North Atlantic was broken. At this point, the British and subsequently the Americans occupied Iceland in order to keep the Germans away. In 1944, the Icelanders declared their country a republic.

The Faroe Islands, on the other hand, remained a Danish county (amt), though isolation from Denmark and co-operation with Britain during the two world wars also aroused a desire for independence among the Faroese. In 1946, a referendum called by the Faroese population resulted in a majority for independence. The Danish authorities rejected this wish based on the fact that both voter turnout and the size of the majority were too low, but the referendum was enough to set the independence process in motion. In 1948, the Danish parliament granted the Faroe Islands home rule, albeit under the Danish monarch, with Danish currency and subject to Danish defence and foreign policy.

Greenland was more closely connected to Denmark. The Danish claim to a trade monopoly had long been challenged by major international powers, but in line with other countries the USA recognised Denmark’s sovereignty over the whole of Greenland as part of the deal over the sale of the Danish West Indies in 1917. Norwegian interests in seal-hunting in eastern Greenland meant that Danish dominance was contested in the inter-war period, but in 1933 the International Court in The Hague confirmed that Denmark had sovereignty over the entire area. During the Second World War, Greenland came under the control of the American military, as formalised in 1941 by a treaty between the US government and the Danish ambassador to Washington, Henrik von Kauffmann. The government in German-occupied Denmark protested, but the treaty was confirmed after Denmark’s liberation in 1945.

Greenland was not to be another West Indies, however. When the American government offered to buy the strategically important territory for 100 million dollars shortly after the end of the Second World War, the Danish authorities declined, even though such a staggering amount could have benefitted the ailing post-war state. Instead, Denmark restored its political supremacy over Greenland, though it was not able to put an end to the American presence. In 1953, a new balance was struck between acknowledging post-war demands for decolonisation and maintaining dominance, by re-defining Greenland as an area similar to a Danish county.

Population growth and urbanisation

In 1914, the nation state of Denmark was home to 2.8 million inhabitants, but this figure had risen to more than 4 million by 1945, including the addition of the 160,000 inhabitants of Southern Jutland in 1920. This growth in population was mainly due to the fact that people lived longer as a result of better nutrition, accommodation and living conditions. At the outbreak of the First World War, average life expectancy was fifty-six years for men and fifty-nine for women. By the Second World War, both these figures had risen by approximately ten years.

Population growth occurred in all parts of the country, but particularly in the towns and cities. The population of Copenhagen increased from just under 600,000 to over 900,000 (or 1.1 million if the rapidly growing suburbs and surrounding municipalities are included), and the other major cities developed in a similar way. Aarhus doubled its population from just under 70,000 in 1914 to 140,000 in 1945; Odense went from approximately 50,000 to 100,000; and Aalborg from 40,000 to 80,000.

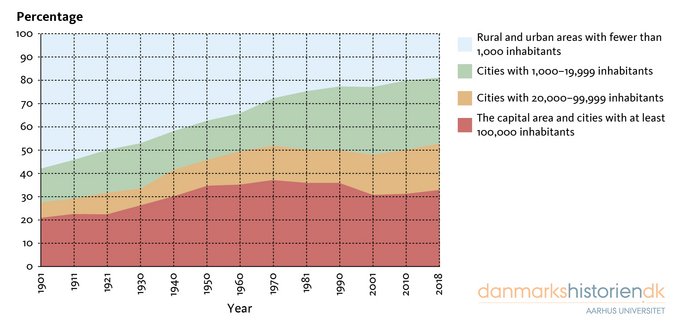

At the start of the period, around a fifth of the Danish population lived in Copenhagen, another fifth in the provincial towns and cities, and the remaining three fifths in the small parish municipalities. At the end of the Second World War, the greater Copenhagen area and the provincial towns between them were home to just over a quarter of the population, while the parish municipalities were home to just under half.

This approximate balance between the urban and rural population was marked by contradictions, however. Agriculture was the most important export sector for the economy, but the growth in industry increased the importance of the towns and cities. As the urban population gained its cultural confidence, the rural community found itself marginalised by industrialists and the labour movement alike, both between and after the wars.

Population distribution between rural and urban areas from 1901 to 2018. Towns and cities had already grown significantly in the nineteenth century, but it was only in the twentieth century that the urban population outnumbered the rural population. In the period between the two world wars – a period often marked by disputes between urban and rural areas – the balance definitively tipped in the favour of the towns and cities. Source: Statistics Denmark

Industrialisation and housing

An increasing number of people started to work in large industrial companies, meaning that population growth was greatest among the urban manual and office workers. On the eve of the First World War, agriculture employed 40% of the working population. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the number of farmers was more or less the same, but this now corresponded to only 29% of the working population, since the total workforce had grown by over 50%. A third of the total workforce was employed in trade and industry in 1940, as opposed to a quarter at the outbreak of the First World War.

The rapid growth in the urban population created housing shortages. In working-class districts people were often living so closely together and in such dilapidated buildings that living conditions were unacceptable. Towns and cities were thus expanded with new residential areas consisting predominantly of rental properties, and surrounding villages were gradually transformed into suburbs, their villas, bungalows and apartment buildings symbolizing modernity and providing more dignified living conditions for the general population.

In contrast, the rural parishes were still shaped by the ideal of self-ownership and individual independence, which manifested itself on many levels, from the manor to the family farm and the smallholding. The number of smallholdings (husmandsbrug) increased following the smallholders’ act of 1919, which guaranteed cheap government loans for new smallholdings set up on land that had previously belonged to a manor or parsonage. At the same time, the village provided the setting for strong local cohesion: economically through the co-operative movement and its institutions; religiously through the village church and pastor; and culturally in the school, library and village hall.

Mobility and infrastructure

The need to move both individuals and goods quickly and efficiently over greater differences meant that the country became more integrated. Since the mid-nineteenth century the railway had connected the larger Danish towns, but it was no longer adequate, so the old steam locomotives were replaced with labour-saving diesel engines and the railway lines were extended. At its peak in the 1930s, the Danish railway boasted over 5,000 km of track – half of which was owned by the state and half by private companies. The many station towns that had sprung up with the expansion of the railway since the mid-nineteenth century mostly continued to prosper. After the 1930s, the total length of track was approximately halved, and the station towns suffered as a result of this decline.

The Danish rail network in 1930. In the 1930s, it was possible to take the train to almost anywhere in Denmark. This marked the culmination of a century of railway development. After the Second World War there was a significant decline in rail traffic, as cars and lorries replaced rail transport. Denmark never established high-speed train links between large towns, which could have made the train a more competitive means of transport. © danmarkshistorien.dk

Other efficient means of transport began to compete with the railway. Although it was by no means commonplace to own a car, there were certainly an increasing number of them, as well as other rubber-tyred motor vehicles, such as buses and lorries. In 1914, there were just under 3,000 motor vehicles, but fifteen years later this figure had risen to 100,000. With these vehicles came new roads, ferry crossings and bridges that linked the mainland to the islands. The first bridge across the Little Belt, which is still used as a rail bridge between Jutland and Fyn, reveals something about the history of its time: built as it was with heavy steel trusses supported by pillars of reinforced concrete, and with a railway line and road in each direction. The resulting structure even breached original plans stipulating that nothing other than a train should be permitted to cross the bridge.

The newest innovation, however, was air travel. Travelling by air seemed just as adventurous and magical to the people of the 1920s and 1930s as travelling by train had to their great-grandparents in the mid-nineteenth century. Not only was it now possible to see the world from above – like the birds and the Lord himself – it was also possible to travel at incredible speed. Following the successes of the Swedish-American Charles Lindbergh, who succeeded in crossing the Atlantic in 1927 with his life intact, and of the Dane Holger Højriis, who achieved the same feat four years later, people began to ponder the dizzying perspectives of air travel. The world seemed to lie open. If one travelled westwards, it would soon be possible to leave Copenhagen at 11am and land in New York at 10am the same day. Humans could now exert an almost divine power over time and place. In 1919, the metropolitan and futurist Danish poet Emil Bønnelycke described air travel as ‘The incarnation of the conquering spirit of the century, / a bold dream, miraculously realised’.

This future reality was still reserved for the wealthy few, however. The average person travelled by train, bus or tram. As bicycles became better and cheaper, they were the affordable way to get to work in growing towns and cities, or to escape into the countryside. The bicycle became the democratic means of transport in the era of the world wars.

Increased mobility bound parts of the country closer together, materially and culturally. Travellers could experience Denmark and the wider world with their own eyes, while even those who stayed at home could learn more about the big wide world from their living room. Newspapers had long reported news and continued to do so. The partisan daily press flourished like never before, and every town of a certain size had its own newspapers affiliated to the main political parties: Venstre, the Conservatives, the Social Democrats and the Social Liberals.

The world could also be heard on the radio, which became a common household item during the 1920s and 1930s. Telephones did not become ubiquitous at quite the same speed, but in 1940 there were 400,000 telephone subscribers in Denmark, which corresponded to a tenth of the population. And people could see the world with their own eyes. The growing number of cinemas showed not only feature films but also newsreels – that is, news coverage in moving images, the cinematic predecessors of television news. Even before the arrival of newsreels in 1917, viewers were able to experience the horrors of the First World War up close in the British war documentary film Battle of the Somme, which terrified thousands of Danish cinema-goers in the autumn of 1916.

While distant lands came into reach, people’s immediate surroundings could paradoxically seem more distant. As farmers began to sell more of their products on the international market there were fewer local transactions. Farmers increasingly had to buy their own food in the market towns, using money earned by producing food for distant markets. In general, the period saw the growing mobility of goods and of people, as they moved between home, work and leisure activities. This trend continued in the post-war period.