2. Growth in the towns and countryside

The European Middle Ages were characterised by a relatively warm period from c. 900 to c. 1300, the so-called Medieval Climate Optimum. The climate was relatively mild, creating extremely favourable conditions for agriculture. New land was cultivated, grain production increased, and towns and trade expanded.

Cultivating new land

Famines and other natural disasters continued despite this growth. Catastrophe always loomed for farmers. The monks of Løgum in western Schleswig complained at the end of the twelfth century that they had suffered ‘cattle disease, the eradication of their sheep, fire in two barns, and another fire that had destroyed the entire area of their monastery and consumed almost all their books, clothes, tools and belongings’. However, there were no major climate-related crises in the thirteenth century and the entire period from 1050 to 1200 offered excellent conditions for population growth. It is estimated that the population of Denmark increased from 500,000 in the Viking Age to at least 1,200,000 in the early thirteenth century.

This increase in population led to the expansion of cultivated land, by at least 50% between 1000 and 1250, according to some estimates. This was usually achieved by clearing forests for the plough. The chronicler Saxo Grammaticus, writing around 1200, described such a transformation in the area around Suså (in southern Sjælland). ‘In the old days’, he claimed, this was ‘densely overgrown with woodland’, but it was ‘now mainly under the plough’. The 1,600–1,700 current Danish place names that end in torp and other variants reflect the growth in agriculture during this period. The suffix torp, which originated during the period 900–1200, denotes a secondary settlement and is today seen in place names ending in trup, -drup and rup. Those who built such settlements could have been independent bønder or slaves (freed or not) who worked for a lord. Another form of colonisation took place on the flat coastal marshes of southwest Jutland, where farms were built on high mounds and dykes were constructed to offer protection from flooding.

Farms and villages

From 200 BC (i.e. the Iron Age), many Danish farms were located in villages – that is, in settlements consisting of groups of farms. 1,400 years later, around 1200, villages were by far the most common form of settlement. In the early part of the Iron Age, villages were relatively mobile, as farming settlements often moved within a defined area of resources. From around 700–800 onwards, however, villages and farms became increasingly static.

Villages in the Middle Ages became bound to specific places, a development that was due partly to burial practices. Whereas Viking-Age burial sites were usually located away from settlements, the dead were now buried in church cemeteries inside the village, which could not be easily relocated. Another reason for the increasing stasis of farms in the Middle Ages was that the right to tax farmers became increasingly tied to delineated and defined areas of land rather than to the individual farmer, meaning that the farm plot became the key determinant of taxes and rents. The most important structural reason for this stability, however, was the shift from livestock to arable farming. Land used to grow grain could produce over ten times as much food energy than land used to graze livestock. In a period of population growth, it therefore made sense to move towards grain production. There was a significant expansion in the amount of land used for arable farming, from 2–5 hectares per farm in the Viking Age to double that in the Middle Ages.

Collectively regulated systems for cultivation

Arable land was used to produce rye, barley, oats and a small amount of wheat. In connection with the move towards arable farming, villagers developed collectively regulated systems for cultivation. This did not mean that the farmers worked the land collectively, but they did coordinate decisions about which crops should be grown when, and how the labour should be organised. More importantly, they co-ordinated ploughing and made agreements about the cultivation of fields and the fencing-off of cultivated areas. Arable land required alternating periods of cultivation and being left to lie fallow. In many places there were orderly systems for rotation, and land that was left fallow was used for grazing livestock. This was not only practical but also necessary to fertilise and avoid exhausting the fields. The collectively regulated systems made it extremely difficult to move villages.

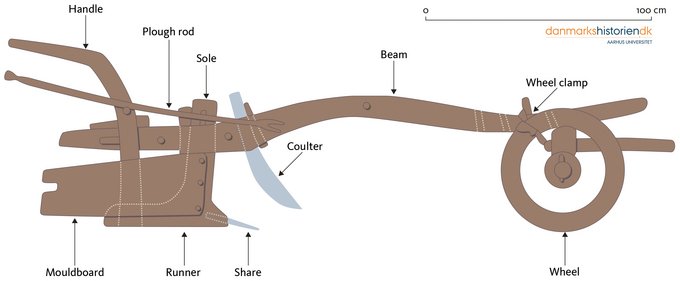

The heavy plough

One of the most important pieces of farming equipment used in the Middle Ages was the heavy mouldboard plough, which turned the soil and thus supplied it with organic nutrients. In many places, the mouldboard plough replaced the older ard (or scratch) plough, which created shallow furrows in the soil but did not invert it. Despite its significance to medieval farming, and contrary to traditional interpretations, it is not possible to claim that the mouldboard plough was responsible for medieval expansion after 1050, as it was already in common use between the third and fifth centuries.

The fields were often long, in some cases kilometres long. This was because the heavy mouldboard plough was difficult to turn. Medieval fields, with ridges separated by furrows that facilitated drainage, were shaped by the way the plough turned the soil. Repeated ploughing meant that soil was turned to the side and accumulated on top of previously ploughed earth. This resulted in fields with undulations of between half a metre and a metre. In its advanced form from the thirteenth century, the mouldboard plough was fitted with a front wheel frame. It was made of wood but had iron inserts and chains, which made it expensive.

Reconstruction of a mouldboard plough with wheel. The mouldboard plough was already in use between the third and fifth centuries in Denmark, but it became more widespread in the Middle Ages and provided the basis for increased cereal crop production. It could turn the soil in a way that improved its productivity. The mouldboard plough remained the dominant type of plough in Danish agriculture until the beginning of the nineteenth century. © danmarkshistorien.dk

Grain production

The plough was drawn by animals, usually oxen but increasingly also horses. Horses could also be used for harrowing and for pulling carts. Horse-drawn harrows were commonly used to break up lumps of soil, to remove weeds after ploughing and to spread manure. Smaller farmers relied on their iron-headed hoes. A long sickle was effective for harvesting grain. The flail, essentially just two rods connected by a chain, also became more widespread and radically increased the speed at which grain could be threshed. The strongest signal of the rationalisation of grain production in Denmark, however, was the construction of mills. Water mills had been built along rivers in the Viking Age, but mill construction really took off in the twelfth century. Kings, aristocrats and monasteries all built mills on a large scale, and towns also acquired their own mills. From the thirteenth century, windmills were also built. Mills were labour-saving constructions that used the power of water and wind to grind grain into flour, rather than the labour of enslaved women.

Urban development

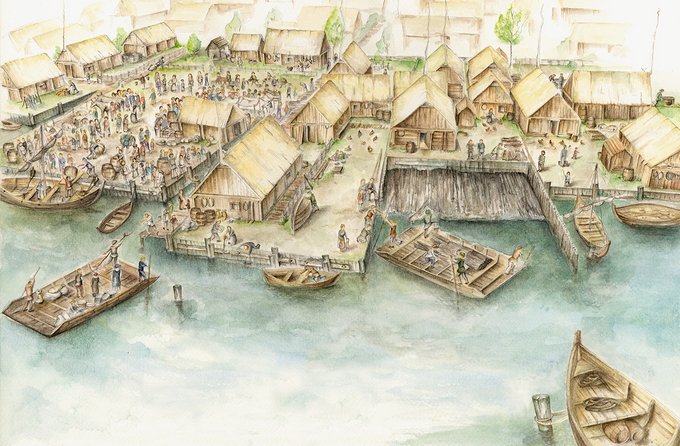

The increase in arable farming and grain production made it possible to feed urban populations. Towns, where people lived closely alongside one another and engaged in business or practised a trade, developed rapidly. Lund (in Skåne), Roskilde, Odense, Viborg and Aalborg were all founded before 1000, and by the middle of the twelfth century there were twenty-two towns in Denmark. A further fifty-five new towns were founded before 1350, most of them before 1250. Most of Denmark was now covered by a close network of towns, and approximately 10% of the population lived in them. Danish towns were not particularly large. Around 1200, the largest urban centres in western Europe were home to approximately 100,000 inhabitants, whereas those in Denmark housed between 1,500 and 2,000 inhabitants.

During the twelfth century, the town of Schleswig became Denmark’s most important trading place, with access to the entire Baltic Sea region and the North Sea (via land routes). This reconstruction of the harbour in Schleswig is based on extensive archaeological excavation. © Felix Rösch, Das Schleswiger Hafenviertel im Hochmittelalter

Urbanisation had a large impact on society, despite the relatively small size of Danish towns. One example of the influence of a town on its hinterland can be seen in an analysis of the wood used for coffins in a cemetery in Lund between 1050 and 1150. In the town’s early years, in the eleventh century, there was enough wood to make coffins from the freestanding oak trees near the town, or the virgin forests full of oak, ash and linden trees nearby. As the trees in the immediate vicinity were felled and the land used for agriculture, forests further afield were also transformed, so that only young and spindly oak trees were available. It became necessary to import pine over long distances. The town certainly left its mark on the landscape.

Episcopal towns and commercial towns

Most Danish towns answered directly to the king, but some were controlled by bishops, monasteries and secular aristocrats. The presence of the king and his officials or of ecclesiastical institutions was particularly important for a town’s success in the eleventh century. Episcopal towns in particular became growth centres that provided the basis for the largest towns to develop. The largest towns centred around cathedrals, such as those in Lund and Roskilde. Many other churches were constructed here: twenty-two in Lund, which was the seat of the archbishop from 1103/1104, and fourteen in Roskilde. Around 1160, Copenhagen – the Danish name of which, København, means ‘merchant’s port’ – was given by the king to Bishop Absalon of Roskilde, who built a castle there to protect trade.

Merchants, and the trade that they conducted, were crucial for the development of towns. Urban markets became the centre of economic life in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Farmers from the surrounding countryside and merchants from abroad would come to the weekly market at the central market square with their goods. The small coastal trading ports of the Viking Age largely disappeared in the eleventh century, with only a few such settlements surviving and developing into market towns. While inhabitants of the early towns often had to grow much of their food themselves and thus required large fields, in the thirteenth century, the king was able to establish urban communities with virtually no arable land. People in these towns could buy grain and meat from farmers in the surrounding region. Køge in southeast Sjælland, which was founded in 1288 and laid out according to a carefully measured geometric system, is an example of a town with minimal arable land. Its inhabitants had to procure food and earn money through trade with the surrounding area and northern Germany. Køge had rights to hold a market from the outset, and its market square remains the largest in terms of area in Denmark.

Coins became the norm

With the creation of a national currency around 1065, it became easier to express value in money and more and more items were given a monetary value. From this point until the fourteenth century, Danish coins were the dominant currency in Denmark. The king, who had a monopoly on minting, only minted one type of coin: the small silver penny. It became more common to use money locally, and many farmers paid their taxes in cash, though payments in kind remained widespread. The numerous medieval coins that amateur metal detectorists continue to find on ploughed fields in Denmark are proof of the widespread use of money during the Middle Ages. Written sources from the period also document that most of the population had cash. One of these sources is a miracle story. Around 1200, following an outbreak of disease among livestock in Halland, sixteen farmers decided to sacrifice one penny each to St Knud Lavard. The disease disappeared, but the money then had to be handed in, so one of the famers made his way to the large herring market in Skåne and found a monk from Ringsted Abbey in Sjælland, where the saint was buried. The monk took the sixteen coins home with him. The story also reveals the extent of international trade at this time, in that the monk had travelled to Skåne in order to trade with foreign merchants.

Danish trade

There were large herring fisheries in the waters off the Falsterbo peninsula in Skåne, which extended into the Øresund opposite Køge Bay. The herring, salted and packed into barrels, became one of the mass products that characterised Danish trade from the twelfth century onwards. Hundreds of thousands of barrels of herring were shipped from Skanør and Falsterbo, the two most important markets and fishing grounds on the peninsula.

Danish merchants had been active in the Baltic Sea trade since the Viking Age. From the 1070s the town of Schleswig was a meeting point for trade between Friesland, Rhineland, Saxony and Westphalia, and Gotland, Sweden, Norway and the Slavic regions. There was regular traffic between Ribe and the harbours of western Europe. From the early thirteenth century thousands of horses were exported each year from Ribe to western European buyers. Some were sold to England, but most were exported to Flanders or ended up in France.

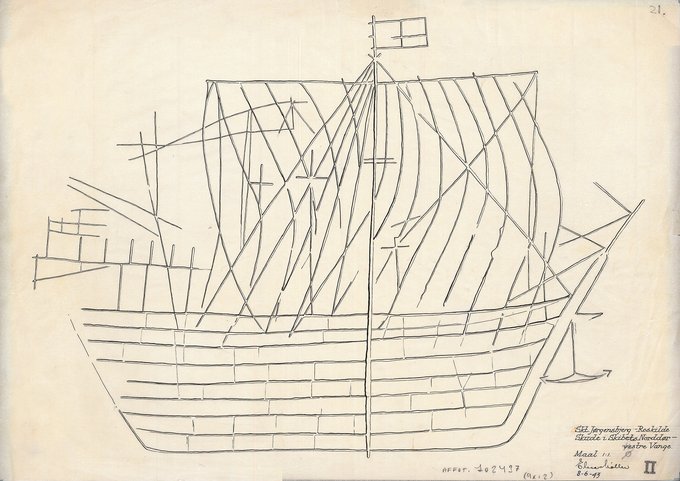

Expanding trade required larger ships. There is evidence to suggest that the cog, a new type of ship that eventually replaced that used during the Viking Age, was invented by Danes. The cog was a flat-bottomed ship, constructed with planks laid edge to edge. It was cheap to build because, unlike the ships of the Viking Age, it did not require first-class wood; it was also cheap to sail, because it could be manoeuvred by just a few men. Several cogs from the mid-twelfth century have been found in Danish waters, and it is generally thought that this type of ship was developed in the southern part of Jutland.

A cog from the first part of the fourteenth century, from graffiti etched into a door frame in St Jørgensbjerg Church in Roskilde. The cog is characterised by its flat bottom, with planks laid edge to edge. Cogs were cheaper to build and operate than the old longships, as they could be constructed with wood of a lower quality and sailed by a smaller crew. Photo: Antiquarian and Topographical Archive, National Museum of Denmark

Traders from northern German towns

The cog soon came to dominate as the preferred craft of the northern German merchants, and large German cogs sailed in the Baltic Sea alongside smaller ships in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. German merchants took over an increasing amount of trade in Danish towns, where royal privileges secured them the right to trade. They sought mutual support in their own associations or guilds, which guaranteed them assistance and a Christian burial if they died abroad. The German merchants came from the recently founded towns along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lübeck was the largest and most active of these towns, but several others, such as Rostock, Stralsund and Greifswald, also established close contact with the Danes. German traders headed primarily to the Skåne markets, where they bought salted herring and exported it (packed in standardised barrels) to large parts of Europe. Around 1200, the chronicler Arnold of Lübeck wrote that the Danes ‘have wealth in abundance thanks to the fishing they do every year in Skåne, on which occasion all the surrounding peoples turn into traders to buy herring from the natives’.

At the Skåne markets, each German town was given its own small area in which to trade and process fish. The safety of the markets was guaranteed by the Danish king, who received taxes in return. Over the course of the thirteenth century, the two small Skåne towns Skanør and Falsterbo came to resemble international trade fairs. During the autumn fishing season, ships from western Europe came to these towns with cloth, spices, Rhine wine and French salt, which were exchanged for products from the Baltic Sea region: cereals, hemp, wax, meat, hides and timber. Danes from near and far and from all levels of society came to Skanør and Falsterbo to buy and sell, and German and Dutch merchants sent their goods onwards from here. It was customary for German merchants, with their cargoes of expensive cloth from the Low Countries, to travel from Skåne to Sjælland and then to take the ferry to Nyborg on Fyn, where Danish consumers were ready and waiting to buy.

The commercial revolution

Through these German contacts, the Danes became part of the ‘world economy’ of the thirteenth century, which, thanks to Mongolian rule – the pax mongolica – spanned vast areas from eastern Europe to China. Long trading routes meant that the wealthiest Danes could enjoy cloves from the Moluccas in Indonesia or cinnamon from Sri Lanka. A Danish cookbook from around 1300 includes a recipe for a luxury sauce using exotic ingredients: ‘Take cloves and nutmeg, cardamom, pepper, cinnamon and ginger in equal quantities, though with as much cinnamon as all the other spices combined, grind them together, mix with strong vinegar and transfer to a container. This is a lord’s sauce that can keep for up to six months’.

More important for the wider population was the exchange of many types of heavy goods, as part of a northern European network. This is often referred to as a commercial revolution. Population growth meant that there was increasing demand for materials such as stone, wood and iron in rural and urban areas. Such heavy materials were best transported by ship. The many churches built across Denmark required baptismal fonts, which alone required hundreds of thousands of tonnes of stone, much of which came all the way from Gotland in the Baltic Sea. It also became increasingly important to secure more food for the growing urban population. From as early as around 1000, people in Danish towns had started eating ‘stockfish’, air-dried cod, which came from Lofoten and other parts of northern Norway. The cod was transported from the north of Norway to Bergen, which became a northern centre for the fish trade under the control of German merchants from the thirteenth century.

The thirteenth century also saw the appearance of a new product from Germany, namely hopped beer, which had the dual advantage that it tasted pleasant and could be transported without spoiling. It was transported in large barrels that contained around 120–130 litres, and then tapped and poured from pitchers. Town councils had the important task of regulating trade in these new goods. In 1281, for example, the town council in Copenhagen was given the authority to set volume measures for German beer.