4. The political development of the kingdom

The Danish realm developed in an interplay between the royal power and the various sections of the aristocracy. Being king was a struggle. This is illustrated in a fresco of a wheel of fortune in Slaglille Church on Sjælland, commissioned by an aristocrat in around 1175. Flanked by two archbishops, the goddess of fortune, Fortuna, spins the wheel that decides the king’s fate. The king could be on the way up, but as soon as he reached the top he was also on his way down. Power in the Middle Ages was unstable, and the constant conflicts among society’s elite could quickly lead to new power constellations. Good advisers and loyal people in local communities could help the king stay at the top of the wheel, if he could control the army and castles, as well as collecting taxes and duties.

State, Kingdom and Royal Power

Watch this film in which Bjørn Poulsen describes the development of the state and power of the monarchy in the period 1050-1340, from itinerant kings and their banquets to the expansion of central administration and the collection of taxes. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and it lasts about eight minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

The king and his kingdom

The king played a pivotal role in holding the kingdom together. From ancient times, people had gathered around the king in his role as war leader. The Christian Danish kings were strengthened when members of their lineage were recognised as saints by the pope. Having royal saints as ancestors provided legitimacy and made it sacrilege to kill the reigning monarch. In the twelfth century, Danish kings also began to emphasise that their office was granted by God, and, from 1170, all Danish kings were crowned, preferably by the archbishop in Lund Cathedral, as a symbol of God’s investiture in them. On an ideological level, important literary works written around 1200 hailed the idea of a Danish fatherland ruled by Danish kings. The most important of these works was Gesta Danorum (The History of the Danes) by Saxo Grammaticus.

The king was thus a key figure for the coherence of the realm, but so too were the people (folket). The realm constituted a legal community – a public sphere. Successive kings had always stemmed from the same lineage, so inheritance of the throne played a role, and generally only one king ruled at once, unlike in Norway, where several kings often ruled simultaneously. However, the king was only elected after the kingdom’s powerful aristocrats had considered the matter and after public debate at central assemblies or army meetings, and several members of the same family could be considered for election to the throne. It was only from the 1160s that it became a firmer principle that the king’s eldest son automatically inherited the throne. And this principle was put under constant pressure by untimely deaths among heirs and aristocrats who sought election to the throne. In 1326, the aristocracy received a royal promise that ‘no other king may be elected in Denmark whilst the king is alive and remains in the country’ and that ‘no assurances or promises of future kings can be made’. The elected king always had to reconcile the exercise of power with the population, especially the aristocrats of the realm, or he risked being killed. From the thirteenth century there were harsh punishments for crimes against the Crown, including regicide, which provided the king with some protection from his subjects.

The king continually had to forge friendships with the aristocracy and to maintain a personal presence throughout the entire realm. In order to do this, he was constantly on the move. Only in winter did the king and his men stay in one place. Large Christmas banquets were held, where the country’s aristocracy gathered and new alliances and loyalties were forged through feasting and drinking. A code of honour guaranteed hospitality and, in principle, peace.

The king’s inner circle

Competent and loyal people surrounding the king could help him in his struggle for power. Originally, the king paid a smaller group of warriors, the hird, to defend him. He also had a group of lay aristocratic advisors by his side, which from the middle of the twelfth century also included the clergy. The clergy were able to counterbalance the secular aristocrats and, with their knowledge of Latin, made it possible to build the first form of central government. Until the 1130s, the king appointed bishops himself, and kings continued to exert influence on their election after this time.

Throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a more orderly administration developed at the king’s court. From 1158, a chancellor was responsible for the king’s documents. He was most often a bishop. A secular aristocrat held the position of seneschal and led the royal court, while the marshal was in charge of the military. Aside from these powerful men, the royal court also included people responsible for serving food and drink, maintaining the chapel and looking after the stores and dining tables. There were assistants responsible for the lights, and an almsgiver who gave money to the poor.

The king’s power reduced when the aristocracy united. This was precisely what happened in the period after the 1240s. From this point onwards, meetings among the higher ranks – both secular and ecclesiastical – began to develop into a political institution, the Danehof. This is discussed further below.

The king and the military

The king was the leader of the realm’s army, from which he secured his authority, provided he actually had control of it. It is difficult to reconstruct the early Danish military system, which was known as the leding. However, we know that it was geared towards naval warfare, and that it rested on the participation of a large proportion of the population. Every one of its operations required support from the aristocracy. When King Svend Estridsen (sometimes known as Sweyn Estridsson) took the Danish fleet to help the German king respond to a Saxon revolt in 1073, there was an uprising among the participating aristocrats, who refused to fight, and he was forced to return home. In the Law of Jutland from 1241, the leding appeared to be well organised and under the command of the Danish king, who most likely had over seven hundred ships at his disposal – a large fleet in a European context. By this time, however, it was common for bønder to pay a leding tax rather than participate in the military themselves. War now became a matter for the tax-exempt aristocrats, the herremænd, who, according to the Law of Jutland, ‘risked their necks for the king and the peace of the land’.

The king’s income

It helped the king’s relationship with the aristocracy that he enjoyed a good income. In the eleventh century, and indeed in the beginning of the twelfth century, the king and the court primarily lived off the duties paid by bønder in the areas in which they stayed during their travels. The Danish Census Book (Kong Valdemars Jordebog) from 1231 included a list of the requirements of the king, his entourage and the local people – eight hundred individuals in total – for a two-day stay: honey, flour, malt, bog myrtle (for brewing and flavouring beer), pigs, oxen, sheep, butter, pepper, cheese, fish, poultry, caraway and oats for the horses, as well as cash. The king stayed at royal manors and, as early as the eleventh century, the country was full of such residences. In the early centuries of the Middle Ages, the king also received silver payments from the North Frisians, who were only partially integrated into the kingdom, and taxes from the towns. He also received income from minting coins and, from early on, he had the right to danefæ, which were goods without heirs or treasure trove.

The king had his own men at the royal manors. They assisted him during his stay, and they collected the military tax from bønder, which became customary in the period leading up to the thirteenth century. In the thirteenth century, the king’s men became increasingly involved in official matters. Whereas earlier they could each hold just one of the two hundred territorial districts (herreder), they now held between two and five. Royal castles became the centres of the new administrative units (len) that developed. As these castles were expensive to maintain, additional taxes were required, and, throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it became customary for the king to collect taxes from the rural population, with the approval of the aristocracy.

The fluctuating power of the monarchy

Between 1050 and 1340, the strength of the realm was highly dependent on the king’s ability to lead and negotiate, as well as to involve the country’s powerful figures in his plans. There had been a radical expansion in the power of the Crown during the Viking Age, when Harald Bluetooth (c. 958–987) built ring fortresses with identical layouts across the entire country. Another significant attempt to expand royal power came when Knud the Holy (1080–1086) levied taxes in order to mobilise the fleet for a raid on England. A third example of strong royal power came in the Age of the Valdemars, the reigns of Valdemar I (the Great, 1157–1182), Knud (1182–1202) and Valdemar II (the Victorious, 1202–1241), during which the country’s governance was modernised.

Each of these three periods of strength ended, however, with the king falling victim to the wheel of fortune. Harald Bluetooth was exiled by his son and died shortly afterwards. Knud the Holy was murdered by aristocrats in Odense in 1086, and the subsequent years until 1157 were characterised by complicated power struggles and civil war between members of the royal household and its aristocratic allies. After the death of Valdemar II in 1241, when the glory years had already passed, a monk from Ryde Abbey near Flensburg Fjord presumably had the wheel of fortune in mind when he wrote that ‘His death truly marked the fall of the Danish Crown, for since then they have been derided by the neighbouring peoples for indulging in internal warfare and selfdestruction’. Following this, power struggles broke out within the royal household and the aristocracy gained noticeably more power.

Roughly speaking, political development in Denmark between 1050 and 1340 can be divided into four phases:

- 1050–1086: A period of growing royal power.

- 1086–1157: A transitional period with weaker rule, during which the king had to carefully align his decisions and actions with those of the aristocracy. At the end of this period, the kingdom was divided into several parts.

- 1157–1241: The Age of the Valdemars, during which the king’s position and institutions expanded considerably.

- 1241–1340: A period during which the Crown maintained its ruling position but only by sharing increasing amounts of land and power with the aristocracy.

The Crown’s distribution of land to the aristocracy and foreign princes eventually led to its collapse. Since the course of medieval history was so dependent on the individual ruler, there is no better way to approach it than king by king.

From Viking Fortress to Medieval Castle

From the Viking ring fortress Fyrkat to the medieval castle Kalø. Watch this film in which Bjørn Poulsen visits the two characteristic fortresses and talks about what they can reveal about the development of society in that era. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about nine minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.

Svend Estridsen and his consolidation of the realm, 1047–1076

Before the period explored in this chapter, the Danes were ruled by a Norwegian king called Magnus the Good (1035–1042). But he was challenged by a member of the Danish royal family, Svend Estridsen, who stepped forward to claim the throne. Svend was the son of Knud (Cnut/Canute) the Great’s (1019–1035) sister Estrid, and had grown up in Knud’s court in England. Svend fought King Magnus without great success, but, in 1047, after Magnus’ death, he managed to become the sole ruler of Denmark.

Svend Estridsen thus came to power as a Viking king, and his repeated attempts to conquer England echo the expansive mentality of the Viking Age. Yet he was also a reformer who took steps that strengthened the kingdom, not only for himself but also for his successors. Around 1065, he succeeded in ensuring that Danish coins were the only money circulating in Denmark. This monopoly enabled him to exploit the monetary system for financial gain – something from which subsequent kings also benefitted over the following centuries. Svend Estridsen promoted the towns and helped the town of Schleswig, Hedeby’s successor, grow to become a central point for trade between Germany and the Baltic Sea region.

A close relationship developed between King Svend and the papacy. The Danish Church belonged to the archbishopric of Hamburg-Bremen, but through his alliance with the pope, the king sought to pave the way for an independent Danish archdiocese. Around 1061, the king reformed the organisation of the Church in Denmark by establishing a fixed system of dioceses. For the rest of the Middle Ages, Denmark consisted of the eight dioceses of Lund, Roskilde, Ribe, Viborg, Odense, Vestervig (which moved to Børglum in the twelfth century), Schleswig and Aarhus. Svend worked closely with the bishops and, upon his death in 1076, was buried in Roskilde Cathedral. He had many children – perhaps as many as thirty – and five of them succeeded him, one after the other, to the throne. This gave rise to what might be called a ‘horizontal line of succession’, as opposed to the more standard ‘vertical line of succession’ from father to son.

Knud the Holy’s expansion of power, 1080–1086

Knud the Holy built on the foundations laid by his father, Svend Estridsen. Indeed, his reign marks an impressive attempt to expand the power of the Crown. Knud, who ascended the throne in 1080, operated in the international networks of the time. He was married to Edel, the daughter of one of the most important figures in northern European politics, Count Robert I of Flanders. There is little doubt that Knud dreamed of building an empire. His ambitions can be seen in his plans to invade England and also in the name he gave his son: Karl (in English, Charles). This name was not connected to the Scandinavian tradition but was a tribute to the emperor Charlemagne (Charles, or Karl, the Great), from whom Edel descended.

King Knud extended his authority by imposing new and heavy fines on those absent from military service and those who needed to reverse their outlawed status. He devalued the Danish currency by reducing the value of silver, and it is also thought that he introduced a poll tax. Knud was inspired by the Church and supported its people. He endeavoured to observe the Christian holy days and periods of fasting, and passed laws that improved conditions for manumitted slaves. The oldest extant Danish letter, from 1085, bears witness to his generous donations to Lund Cathedral.

The murder of Knud the Holy, 1086

Knud’s reforms were unpopular with the population, to say the least, and when he planned an invasion of England with his father-in-law, Robert I of Flanders, there was an uprising. The invasion fleet was gathered in the Limfjord and the warriors were crowded together for a briefing when the unrest broke out. King Knud attempted to calm the rebels but ultimately had to flee with a group of aristocrats at his heels. He took refuge at the royal manor in Aggersborg on the north side of the Limfjord, but it was soon plundered by his enemies. From here, the rebellion swept through Jutland. At the provincial assembly in Viborg, Knud once again tried to negotiate with the rebels. Inconveniently, he then had to travel to the town of Schleswig to take care of border issues, and when he and his entourage sailed from there to Fyn and then headed towards Odense, his enemies were waiting. The royal manor in Odense was taken by the rebel army, and Knud sought refuge in the Church of St Alban. On 10 June 1086, the king was killed in front of the altar in the wooden church, together with his brother Benedict and 17 other men. ‘The holy house was awash with blood’, wrote the monk Ælnoth, who described the event in an account of Knud the Holy’s martyrdom. Knud’s wife Edel and his young son Karl, who was supposed to succeed Knud to the throne, fled to Flanders, where Karl later became its count.

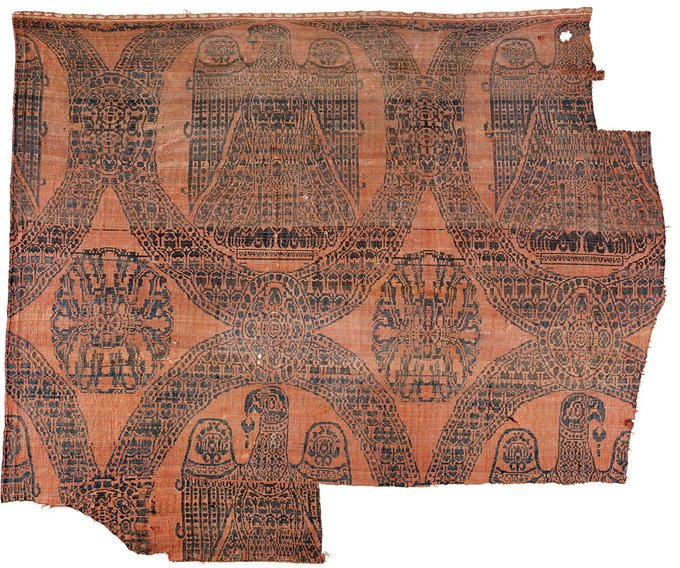

Knud the Holy was killed in Odense in 1086. In 1100 or 1101, his earthly remains were exhumed and laid in a holy shrine in the town’s Church of St Knud. They were wrapped in this purple-coloured byzantine silk cloth with eagle motifs. Photo: National Museum of Denmark

The creation of a royal saint, 1086–1104

Knud’s murder demonstrated that it was impossible to disregard aristocratic networks. His ambition to break the ‘horizontal’ line of succession (whereby Svend Estridsen’s sons claimed the throne in turn) and have his son elected as king did not come to fruition. However, his murder was eventually used to the benefit of the Crown. In 1100, having presented his case to the papacy, Knud’s brother King Erik I (Erik the Good) succeeded in getting Knud recognised as a saint. With this canonisation, Knud became one of the first European royal martyrs. Clergy were able to document that miracles had taken place at his grave, which proved his holy status. Knud’s earthly remains were laid in a golden shrine on the altar in the church in Odense, which was consecrated in his name. The Church of St Knud became a cathedral and a pilgrimage site connected to the royal family. The cathedral subsequently gained a monastic community of English monks, who soon became the bishop of Odense’s canons.

Erik I also strengthened the realm, though by different means. The Danish kings had long pursued the policy of making the realm independent of the German archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen, by which it was ecclesiastically governed in the eleventh century. In 1103/1104, Erik I finally succeeded in obtaining papal approval to upgrade Lund to an independent Nordic archdiocese. Bishop Asser in Lund became the first Danish archbishop, and led missionary activities in both Norway and Sweden. In 1124, he even ordained a bishop of Greenland. Asser took office at the same time as King Niels came to the throne in 1104.

King Niels and the murder of Knud Lavard, 1104–1131

The period between 1104 and 1157 was generally characterised by the weakness of the Crown. One indication of the weak and uncertain standing of the kings is that four of them were assassinated during this period. Another is the loose line of succession within the royal family.

King Niels (1104–1134) ruled in close collaboration with the country’s aristocracy and by accepting that members of the royal family were in charge of certain parts of the kingdom. Niels’ nephew, Knud Lavard, was awarded the title of duke and given responsibility for the most important trading town, Schleswig. Knud became a powerful figure here, earning the epithet Lavard, meaning ‘bread giver’ or ‘lord’. In 1129, the German king, Lothair III, offered him the title of King of the Abodrites, a Slavic people, making him ruler of a new kingdom that stretched from Mecklenburg to Schleswig. This was of course a situation that alarmed King Niels and his son Magnus, who feared that Knud would take over. When Knud celebrated Christmas with the king in Roskilde, the Crown was the first to strike. On 7 January 1131, King Niels’ son Magnus and a group of men killed Knud in a forest. A later text describes how Knud’s head was sliced from his left ear to his right eye so that his brain flowed out, and that, following this, all the murderers pierced Knud’s chest with their spears. King Niels prevented Knud’s burial at the usual royal burial ground in Roskilde; instead, he was buried in Ringsted.

The beginning of the civil war period, 1131–1146

The murder of Knud Lavard threw the kingdom into internal unrest. Two kings faced each other in open conflict when Knud’s half-brother, Erik Emune (Erik the Memorable), used the provincial assemblies to incite a popular uprising and was elected as a rival king. Both King Niels and his son Magnus now tried to win the support of Lothair III, who by this time had gained the title of emperor. Magnus succeeded, and in 1134 he became the emperor’s vassal, meaning that Denmark became a German fief. This was no help, however, as King Niels and his army were defeated by Erik Emune’s forces at Pentecost in 1134. Magnus, four bishops, sixty priests and many aristocrats were killed during the battle at Fodevig in Skåne. Another bishop later died of his wounds. King Niels fled by ship to the town of Schleswig, where he met his fate; he was killed by citizens angry about the murder of their lord, Knud Lavard.

Erik Emune ascended the throne in 1134 as sole ruler and became known for his ruthlessness. He immediately killed eleven members of his family whom he classed as potential rivals. Erik sought to legitimise his position by campaigning for the canonisation of his half-brother Knud Lavard, and he established a Benedictine monastery near Knud’s grave in Ringsted. But opposition was strong, and culminated in him being stabbed with a spear during a public assembly meeting in Jutland. His successor did not last long and abdicated in 1146.

This left two royal individuals with an equal claim to the throne: Magnus’ son Knud (V) – King Niels’ grandson – and Erik II’s son Svend Grathe. The former was elected as king in Jutland, and the latter in Sjælland and Skåne. Denmark was thus divided, standing on the brink of a new civil war. The Chronicle of Roskilde claimed that ‘the internal unrest led even peaceful people to revolt’. A complex game of alliance began.

The struggle of the three kings, 1146–1157

The co-regency was not sustainable. A dispute between Knud V and Svend Grathe developed, and fighting broke out. The situation was further complicated when another stakeholder arrived on the scene, namely the son of the murdered Knud Lavard, Valdemar (later Valdemar I, ‘the Great’), who lent his support to Svend Grathe. Knud V had to flee immediately, but he found an ally in Germany.

In 1152, the powerful German king and later emperor Frederick Barbarossa (‘Red Beard’) called the two Danish kings to an assembly. His judgement was that Knud should not be king, but should rule over Sjælland. Svend, on the other hand, was to become Frederick’s vassal with the title King of Denmark, and Denmark thus remained a fief under the German emperor until 1182. Knud Lavard’s son Valdemar was given control of Schleswig. Svend was unpopular as a ruler, however, and in 1154 it was his turn to flee to Germany. In the same year, Knud and Valdemar I were hailed as Danish kings at the provincial assembly in Viborg. Alliances changed quickly for calculated, strategic reasons.

In the winter of 1156–1157, Svend Grathe returned with an army and gained a foothold in Denmark. A settlement was negotiated that divided Denmark in a new way: Svend received Skåne, Knud V received Fyn and Sjælland and Valdemar received Jutland. Hostages were exchanged to safeguard the deal, and, in August 1157, a peace banquet was arranged at the royal manor in Roskilde, intended to seal the reconciliation. Everyone swore an oath to keep the peace, but the banquet ended in betrayal when Svend’s men killed Knud and others. The banquet became a bloodbath. According to the surviving sources, Valdemar was only able to escape the banquet by overturning the lights. He fled, seriously wounded, and raised an army.

Valdemar’s army faced Svend’s army at Grathe Hede (Grathe Heath) south of Viborg, and Svend was defeated. On the heath that would later give him his epithet, Svend met his death with a blow of a farmer’s axe. Following this royal murder, there was once again only one Danish king: Valdemar I (the Great, 1157–1182). King Valdemar immediately marked his victory by founding Vitskøl, a Cistercian monastery near the Limfjord. In the founding charter, Valdemar described his version of the bloodbath in Roskilde, where ‘faithless men’ with ‘drawn swords suddenly tried to kill me, an unarmed man’, but God was on his side.

The Age of the Valdemars, 1157–1241

The power of King Valdemar I (the Great) was demonstrated at the so-called Church Festival in Ringsted in 1170. It was here that Denmark’s first coronation took place, when the archbishop crowned Valdemar’s son, seven-year-old Knud VI, as co-regent. The line of succession was now secured, and this tied in perfectly with the Church’s pronouncement of monogamous marriage as the basis for creating legitimate heirs. Kings still had to be acclaimed, however; Knud VI only succeeded his father as king once he was acclaimed in the provincial assembly following his father’s death. The legitimacy of the royal line of succession was further safeguarded when Valdemar I’s father, Knud Lavard, was canonised by the pope, which was also celebrated at Ringsted in 1170. The holy shrine was placed on the altar, and texts were read that described how the Lord had made St Knud the leader of God’s people.

One sign of the Crown’s expanded horizons was that candidates for queen were sought abroad. Instead of taking wives from the local aristocracy or from the Nordic or nearby Slavic regions, Danish kings now married prominent women from central European states. Knud the Holy had taken the lead by bringing his queen to Denmark from Flanders. Valdemar I married the daughter of a Russian prince, Sophia of Minsk, whilst Knud VI married the daughter of one of the most powerful men of the time, Duke Henry, the Lion of Saxony, and Valdemar II went even further by marrying Dagmar of Bohemia and, after her death, Berengaria of Portugal. This international alliance policy reached its (short-lived) peak when Valdemar I’s daughter Ingeborg married one of Europe’s most influential men, King Philip II Augustus of France. The union ended in disaster when the French king rejected Ingeborg after the wedding night. This initiated a complicated, twenty-year-long process, since Canon Law only recognised divorce in extreme cases.

The king and the Hvide family, 1157–1241

The kings enjoyed a powerful position between 1157 and 1241, as previous internal fighting had weakened the aristocracy and constrained their networks. The king had to remain constantly vigilant against contenders to the throne from within the royal family, but large sections of the aristocracy had been eliminated in the civil wars, which meant that he could rely on the support of the dominant aristocratic family in Sjælland, the Hvide. He could thus implement his will with minimal resistance. One of the most important members of the Hvide family was Absalon, who became bishop of Roskilde immediately after Valdemar I ascended the throne in 1157. In an unprecedented move, Absalon later merged this bishopric with the archbishopric in Lund.

The Hvide family’s symbiotic relationship with the monarchy is evident from the fact that they were part of an ongoing construction of a more formal central administration. Members of the family were appointed to positions such as chancellor and seneschal, and many of them became bishops. The period was thus characterised by effective co-operation between Church and king, and ecclesiastical legislation gained ground.

Domestic governance in the Age of the Valdemars, 1157–1241

Having a fixed line of succession and a saint as a father embedded the king’s position after 1157, and this was combined with a royal ideology that strongly emphasised God’s close relationship to the king. The monarch was compared to the Messiah, and it was made clear that his power came directly from God. According to this official ideology, the king and his officials had the duty to ensure the safety of everyone in the kingdom. Vulnerable people such as widows, children without guardians, pilgrims, foreigners and the poor were to be protected. In reality, however, caring for the poor and the sick was the domain of the Church or the family. It is still not possible to describe the kingdom as a ‘state’, understood as a central political organisation with a monopoly on law and order within a given territory. The Church’s jurisdiction meant that power was always divided. However, the central administration expanded, partly inspired by the English model, and written laws provided a more uniform jurisdiction throughout the kingdom.

One source describes a relatively well-functioning royal local administration: the so-called Danish Census Book (Kong Valdemars Jordebog), a collection of lists of local royal revenues from around 1231. It shows that there were local officials, ‘ombudsmen’, throughout the country who paid duties to the king and provided for him during his travels. The king received sizable payments from the growing towns but also taxes from the rural population. These taxes were created partly to replace the requirement to accommodate the king during his travels and partly to replace the military tax levied on the rural population. The royal estates were not overly extensive and had less significance for the royal finances, accounting for only an estimated 5% of the total cultivated land in the country.

Military expansion in the Age of the Valdemars, 1157–1241

The well-run kingdom made it possible to conduct conquest raids. In Valdemar the Great’s grave in Ringsted Church, two leaden plates have been found that summarise his achievements. The latest of the plates, from around 1202, describes Valdemar as ‘the mighty conqueror of the Slavs’. During the twelfth century, the war against the pagan Slavic peoples on the southern shores of the Baltic Sea became a major concern for the Danish king, the Saxon duke Henry Lion and the Holstein counts. There were sound strategic reasons for turning against the Slavic peoples. Internal disputes before 1157 had given them free rein to plunder and capture slaves in Denmark. Saxo reported that villages in the eastern part of Jutland from Vendsyssel to Ejderen were abandoned, and a will from 1183 mentions properties in Mols but adds that they were of low value, since they were by the sea and at the mercy of heathen raids.

Archaeological findings show that, in many places in the twelfth century, Danes attempted to protect themselves by erecting wooden barriers in domestic waters. The king and his closest men created a solid coastal defence with stone castles in Copenhagen, Kalundborg, Vordingborg and Sønderborg, in addition to Tårnborg (near Korsør) and the castle on the island of Sprogø. Valdemar I also reinforced parts of the old Danevirke fortification on the southern border. From 1158 there were annual raids against the Slavs, particularly on the island of Rügen. In 1168, Danish fighters stormed the Arkona fortress on the island of Rügen, which was home to the shrine of the god Svantevit. The fortress was captured, the statue of the four-headed god was burned, and all the island’s inhabitants were forcibly Christianised. From this moment on, Rügen belonged to

The island’s conquest was a bridgehead for further Danish expansion, first in the nearby Slavic regions, later (in the 1180s) against the Prussian tribes in the east and, finally, all the way to Estonia. The raids were not only about conquests, but also created peace and helped to unite a country that had just emerged from civil war.

In 1168, the Danes conquered the Slavic island of Rügen, whose main town was Arkona. Around 1200, the event was recounted by the chronicler Saxo; later it became important to Danish identity. In 1894, Laurits Tuxen (1853–1927) painted a famous picture of King Valdemar the Great and Bishop Absalon leading the destruction of the statue of Svantevit in Arkona. The painting can be seen here reproduced as a lithograph, which was used during object lesson teaching in schools at the end of the nineteenth century. From: Royal Danish Library

The Valdemars’ relationship with Germany, 1157–1241

At the beginning of his reign, Valdemar I had to swear obedience to the German emperor. In 1162, accompanied by Bishop Absalon, he travelled through Germany to the meeting place at Dôle (now in eastern France). Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, who had just conquered Milan in Italy, held a triumphant ecclesiastical council and imperial assembly here, and Valdemar had to pledge humble allegiance to the emperor by placing his hands in his. He also swore to adhere to the emperor’s policy on the papacy. The Danish kings soon managed to release themselves from their dependence on the emperor, however. Valdemar I’s son and successor, Knud VI, who ascended the throne in 1182, refused as early as 1184 to renew his allegiance to the emperor. Instead, he continued the Danish expansion into northern Germany with the conquest of Pomerania. In 1201, the Danish army conquered Holstein and occupied the German cities of Hamburg and Lübeck.

When the newly crowned King Valdemar II (the Victorious), Knud VI’s brother, invaded Lübeck in 1202, he was recognised by the German emperor as ruler of all the land north of the River Elbe. He then expanded across the Elbe, and a real ‘empire’ emerged to the east. This expansion, which often took the form of a crusade, culminated with Valdemar II’s conquest of Tallinn in Estonia in 1219. With this, however, the Danes had extended their rule over more than they could sustainably control. Disaster followed disaster, and the ‘empire’ fell apart.

The Danish kings were avid hunters, and one evening in 1223, amidst the conviviality following a hunt on the small island of Lyø, Valdemar II and his son, also called Valdemar, were taken prisoner by a German count. It was only after years of imprisonment, the payment of a huge ransom and the relinquishment of most of the conquered territories that the two royals were released. Their attempt to regain what was lost led to the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227, where a Danish army was defeated by a coalition of German princes. The island of Rügen remained under Danish rule, however, and the pope’s intervention secured northern Estonia for the Danes until 1346, when the area was sold.

Map of the Baltic Sea Region with the Danish ‘empire’ in the early thirteenth century. From 1201, the Danish king had control of Holstein and Pomerania; in 1219, he also ruled in parts of Estonia. A few years later, the ‘empire’ fell apart. © danmarkshistorien.dk

Ruptures in the line of succession, 1241–1340

The period 1241–1340 was one of increasing disaster for the Crown and its territories, partly because there was one dramatic break after another in the line of succession.

Valdemar II (the Victorious) had presumed the line of succession was safeguarded when his son Valdemar the Young was crowned co-regent in 1218. However, the future of the monarchy became uncertain after Valdemar the Young was killed by an accidental shot during a hunt in 1231. Another legitimate son, Erik, was crowned in 1232, taking the throne after Valdemar the Victorious’ death in 1241. Yet Erik was unable to succeed his father uncontested. From the moment he ascended the throne, Erik IV Plovpenning (1241–1250) had to contend with a challenge that was the creation of his father: the dukedom Sønderjylland or Schleswig, which Valdemar had founded by handing it over to another son, Abel, Erik’s younger brother.

Shortly after 1241, a war broke out between the two brothers, Denmark’s King Erik and Schleswig’s Duke Abel. In 1250, it seemed that a settlement could be reached, and the two men met each other at Abel’s court in the town of Schleswig. But the meeting turned out to be a trap, and the king was captured and killed. News of the deed spread throughout Europe, but Abel managed to clear himself of complicity and could even take over the throne, as Erik had no sons. His reign did not last long, however; the army was attacked during a campaign led by Abel (1250–1252) two years later, intended to recover taxes from the North Frisians. In the confusion, King Abel himself was killed by an arrow. Since Abel’s son was imprisoned abroad, an opportunity arose for a third of Valdemar the Victorious’ sons, Christopher I (r. 1252–1259), who died not long into his reign. The wheel of fortune turned quickly.

Finally, in 1259, a royal son was once again able to succeed his father as monarch. Supported by his mother the queen, nine-year-old Erik V (Klipping) ascended the throne. When he formed his own independent government, he immediately encountered opposition from the aristocracy, and this culminated on a November night in 1286 when he was killed in Finderup Lade near Viborg. This was the last regicide in Danish history. Erik Klipping’s son, Erik VI Menved, took over as king but died childless in 1319, so it was once again a king’s brother who ascended the throne, Christopher II. In 1326, Christopher was deposed by a group of aristocrats led by a Holstein count, and a child duke from Schleswig was put in his place as the Danish king. Christopher regained the title for a short period, but, upon his death in 1332, Denmark was left without a king.

The conflict with the Church, 1240–1340

In the years after 1240, the Crown had considerable judicial power, supported by a system of fortified castles. Other social groups also consolidated their positions. The townspeople gained their privileges, the secular aristocracy became stronger and stronger and the power of the Church and its bishops grew so strong that a state under dual leadership came into existence. In many ways, the Church built up an apparatus parallel to that of the monarchy. The archbishop and bishops had central administrations, armed men and castles, just like the king. The archbishop ruled from the heavily fortified Hammershus castle on Bornholm.

With a certain inevitability, there thus arose a conflict between the king and the Church, fuelled by the ecclesiastical theory that the Church was superior to secular power. The interests of the king and the Church collided on many issues. The boundaries between secular and religious jurisdiction – that is, the right to pass judgement – were not sharply defined. It was not clear whether the Church should influence who became king, or whether the king should decide who became archbishop. The bishops did not wish to contribute to the military defence of the realm, and the king attempted to gain a share of the Church’s income.

From the mid-thirteenth century, there were therefore constant disputes between the Crown and a number of archbishops. The king used all the resources at his disposal and did not shy away from incarcerating the archbishops, but the latter often had the pope on their side. There was extremely poor collaboration between the king and the Church.

A Danish parliament, 1240–1340

From as early as the twelfth century, the king had collaborated with the highest-ranking members of the secular aristocracy and bishops. In the second half of the thirteenth century, this collaboration took place at assemblies where the aristocracy from across the realm gathered. These assemblies were held more frequently and were given the name hof (‘court’) or Danehof (‘court of the Danes’). They became a type of parliament, where laws were passed and taxes were granted. Following the European model, there thus developed control over the king.

This control went so far that, in 1282, aristocrats at a Danehof assembly in Nyborg demanded a so-called håndfæstning from King Erik Klipping – a charter that guaranteed the privileges of the secular aristocracy and the Church, in some ways similar to the English Magna Carta of 1215. With this, the king’s right to use his own court was curtailed, along with his right to levy taxes and require forced labour. More importantly, the king had to promise to summon the Danehof every year, so it became a stable form of control, and it was decided that this institution should rule over cases of crimes against the sovereign power.

The murder of Erik Klipping in 1286 in Finderup Lade clearly shows that these royal pledges were not enough to satisfy the opposition. We do not know which – or how many – of the king’s opponents played their part in the fifty-six stab wounds Erik Klipping reportedly received. But we do know the verdict of the case. Whereas kings had once been killed openly, regicide was now a crime to be concealed, for it carried harsh punishments. The Crown, represented by a caretaker government, used Erik’s murder as an opportunity to eliminate the opposition, and nine high-ranking men were convicted of crimes against the sovereign power at the Danehof in 1287. The nine were given protection by the Norwegian king; one of them, Stig Andersen Hvide, built a castle on the small island of Hjelm, from where he engaged in piracy and large-scale counter-feiting operations.

In the years that followed, the Danish kings pursued an aggressive foreign policy, but their aristocratic creditors got the upper hand. This can be seen in the håndfæstning that Christopher II had to submit in 1320. In this document, the king agreed that the Danehof represented a higher authority than his own court, and, among many other things, he promised to pay his debt, to excuse the secular aristocracy from fighting wars abroad and to demolish a number of royal castles. The håndfæstning exhibited the weakness of the monarchy, and it divided society into distinct groups: the churchmen, knights and squires, and burghers. Independent bønder were also mentioned, but tenant farmers were represented by their aristocratic lords. In the period that followed, society began to be divided into legally defined groups called ‘estates’ (stænder).

The financial challenge, 1240–1340

In the first part of the fourteenth century, Denmark faced elimination as a political unit. This was because it was not supported by central taxation; instead the holding of land and castles was delegated to aristocrats. The Crown competed militarily and for status with other European princes, and this was difficult to finance. The royal castles, which covered the country, were particularly expensive to maintain. They were so costly that all the revenue from these areas was spent on their upkeep.

The disintegration of the kingdom began during Valdemar the Victorious’ reign, before 1241, when the king gave his sons duchies. The creation of the duchy of Schleswig was particularly fateful. Throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it became increasingly customary for the king to raise funds by mortgaging the country’s administrative districts (len) and their castles to wealthy nobles and princes. Money could now be directly exchanged for power.

As early as 1325, almost half the len were mortgaged and, in the interregnum of 1332–1340, the entire realm was under the sovereignty of Holstein or Sweden. Taxes were levied, which, together with frequent crop failures, weighed heavily on the population. The effects of this were clear. There were more uprisings. One chronicle describes how, in 1312, the king had many peasants hanged outside Copenhagen. In 1313, there was a large revolt against the king in northern Jutland, and, in 1328, a tax rebellion broke out among the rural population of Sjælland. The king also lost tax revenue when tax-paying bønder entered into tenancy agreements with the aristocracy and were no longer obliged to pay taxes to the crown. The king’s tax base dissolved.

On the other hand, the aristocracy sought to secure their loans to the king – it was aristocratic creditors who removed Christopher II from the throne in 1326. This meant that from 1332 the greatest creditor, Gerhard III, Count of Holstein (the ‘bald count’), became Denmark’s de facto ruler and commanded a puppet government. Keen entrepreneurs, including the Holstein counts, other German princes, Danish aristocrats and the Swedish king, acquired mortgages on len after len in Denmark.

The kingdom crumbled. A song of lament from 1329 mourned the loss: ‘Sigh and wring your hands / Sorrowful fatherland!’. The country was left without a king until 1340 and, as a result, all minting west of the Øresund came to a standstill.