2. The structure of society

The vast majority (80%) of the population continued to live in the countryside, with the rest divided equally between the ordinary towns and the capital, Copenhagen. The distribution between town and countryside did not shift significantly during the period, but social patterns gradually changed. The hierarchies in the society of estates became clearer. A small, powerful elite of noble landowners with enormous economic power stood out from the rest of the manorial lords. At the beginning of the period, the large middling group within the rural population – the tenant farmers (gårdmænd) – had been weakened by war and crises, but with economic recovery and agrarian reforms they gradually came to exercise considerable power. Similarly, economic progress and international trade at the end of the eighteenth century meant that the burghers gradually emerged as a politically, economically and culturally significant group. Population growth across the whole of society led to growing numbers in the lower social strata in both the towns and the countryside. The numbers of tenant farms, merchants and master craftsmen were fixed, so the increased population could only be absorbed by the lower levels of society.

Provincial towns

Towns varied in size. Most had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants; larger towns like Odense, Aalborg and Helsingør had around 5,000. Small towns were usually not much different in size from large villages, but there was a sharp division of labour between town and countryside. The towns had the monopoly on trade and most artisan production – for example the distillation of spirits. There were also large cultural and economic differences.

The rural population was much poorer than the urban population throughout the second half of the seventeenth century and the eighteenth century. It was only with the agrarian reforms at the end of the century that a farmer elite reappeared in the countryside.

The largest divide in the towns was between the burghers and other social groups. Merchants and craftsmen were classified as burghers and thus enjoyed a special status. Together with officials and pastors, they constituted the town’s top social layer. Day labourers, sailors, servants and recipients of alms all lacked burgher status, as did those training to practise a particular craft.

Trade organisations were important for the social structure of the town. Craftsmen belonged to the guild (lav) for their trade, which had a monopoly on craftsmanship and regulated prices and the number of permitted masters. The guilds also served as a social safety net, as members supported each other in the event of illness or death. A woman could not officially run an independent business, but she could operate a workshop as a widow if her husband died. Petitions to the king show that women acted as independent business owners, even in trades different from their husbands’. Journeymen were organised in guilds in a similar way to their masters. In addition, they were members of their masters’ household, and subject to their authority.

Copenhagen

Copenhagen was radically different from other urban settlements due to its size. The capital was home to the king and the court, the government, the central administration, the navy, a large part of the army and the university. This led to far greater and more diverse consumption and trade than in other parts of the country. Most international trade was conducted via Copenhagen, which contributed to creating a wealthy burgher estate in the capital. This estate included officials connected to the central administration. The nobility was also present in large numbers, for the presence of the king, the court and the central administration in the capital meant that it was necessary for nobles to have Copenhagen mansions. The ownership of such properties was a demonstration of their rank and influence. But the capital was home not only to the elite, to political decision-makers and to high culture. As a large city, it was also home to poor people, petty criminals and prostitutes, who fought for survival in the narrow, dirty streets and backyards.

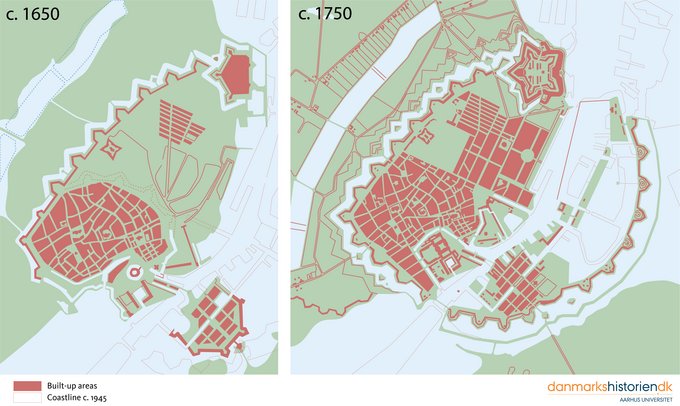

Plans of Copenhagen in 1650 and 1750, which show how the capital expanded during the period. Between 1672 and 1730, the population of Copenhagen grew from approximately 42,000 to 70,000. In 1728, the city was hit by a fierce fire and about a third of the old centre went up in flames. Approximately 1,500 properties, six churches and a part of the university burned down in the fire. The capital was once again hit by a major fire in 1795. The map shows how, after the introduction of absolutism in 1660, the fortification system was expanded, with the Citadel (Kastellet) completed in 1666. © danmarkshistorien.dk

People in the countryside

Property and living conditions in the countryside varied considerably in the king’s territories, meaning that there were major differences between Demark, Norway, Iceland and Schleswig and Holstein. In Denmark, manor (herregård) owners were at the top of the social hierarchy. These rich noble landowners accounted for only a very small section of the population, but they owned virtually all farmland, together with the king. Some of the land was cultivated directly under the demesnes, but the vast majority of it was rented out, either to tenant farmers (gårdmænd), who rented a tenant farm (fæstegård) and accompanying land, or to landless cottars (husmænd), who rented a small house with minimal or no land. Tenant farms were typically large enough to feed a family and a few farmhands and servants. The landless cottars were beneath tenant farmers in the social hierarchy, and their smallholdings were often too small to support a whole family. These smallholders were therefore also forced to work as casual labourers on both manor farms and tenant farms, or to engage in other economic activities such as fishing, charcoal burning or small-scale pottery production. For many tenant farmers, secondary occupations were also an important part of their income.

The number of landless cottars increased from approximately 25,000 to approximately 110,000 during the period, mainly because the number of tenant farms was fixed, so population growth forced more into the smallholder class. Many smallholdings had no land, but smallholdings with land were also set up on manorial land, where they could supply labour.

In addition to tenant farmers and smallholders, the rural community also included servants on manors and farms, as well as those without their own household who rented space in another or lived there as pensioners. Like the towns, villages were also home to society’s lowest level of poor, who were dependent on the charity and support of others.

In the rural social hierarchy, royal officials were placed between mostly noble landowners and tenant farmers. They distinguished themselves by adopting an urban culture. Such officials could include bailiffs (ridefogeder and herredsfogeder) and pastors. The Lutheran pastors were not only responsible for ecclesiastical tasks, but also served as the king’s officials at the very local level. They announced new legislation from the pulpit, registered births, deaths and marriages in the parish records and endorsed servants’ employment record books when they moved between parishes. The precise registration of the population carried out by the pastors created the basis for an accurate overview of population size and distribution, which was useful when levying taxes, among other things. The pastor also enjoyed a special status in the local community, since the rectory farm and the pastor’s household were intended to serve as examples for the rest of the population. However, this was not always the reality, for there were cases of drunkenness and abuses of power among the parish pastors.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, farms were usually located in villages. The land was divided and individually cultivated according to the same principles as in previous centuries, and everything was regulated and co-ordinated through the village community, the activities of which were defined by the village bylaws (vider). These stated how much the individual farms could use common land according to the size of their farms, how much help they were expected to offer to rebuild a farm following a fire, for example, and what their duties were in the event of illness. The vider also included provisions for the conduct of the village assemblies and rules for a system of fines that was used to help support the poor. One of the major social changes in eighteenth-century villages was the break-up of this village community, which came with the agrarian reforms.

The household and its members

The household constituted the basic unit of both urban and rural society. It was also the basic unit of production, and often included more than just the nuclear family. An individual’s opportunities and position in society was determined not only by gender and social affiliation, but also by marital status. As a rule, marriage gave both men and women the status of head of a household, meaning that, as well as having authority over the children and servants, they also had responsibility for the household. Around 10% of the population remained unmarried throughout their lives, and thus formed part of others’ households. For those who did marry, the average age to do so was relatively old – almost 30 for women and just over 30 for men. The vast majority had worked in service for shorter or longer periods before they had the opportunity to marry. People only got married once they could support themselves and a family, and thus establish themselves in their own household. Marriage and the household were social structures that had shaped society since the Late Middle Ages.

Gender and the division of labour in the home

Men had overall responsibility for the household. In the countryside, this meant ensuring that the farm was run properly, and, in the town, that the household’s craft or trade was conducted properly. As a consequence of this, work tasks were largely linked to gender. The male servants, boys and journeymen worked the fields and took care of the animals, or managed the trade or craft. Housekeeping was a woman’s responsibility, and the female servants and girls worked together with the mistress to prepare food, take care of the children, wash, make and repair clothes and perform other household work. Rural women were also responsible for specific agricultural tasks in relation to both the fields and the animals. Milking, for example, was an exclusively female activity, and during the harvest it was women and girls who tied up the sheaves of grain after the men had cut it. The married couple were at the top of the household’s hierarchy and led and delegated the work. The lower an individual was positioned in the household hierarchy, the more manual and heavy work they performed.

According to the law, the master and mistress (husband and wife) had both the right and the duty to discipline their children and servants, within what were then seen as reasonable limits. They were not allowed to use unnecessary violence or inflict permanent damage. Children were obliged to obey their parents; those who exercised physical violence against their parents could face the death penalty. Servants were also bound to obey their master and mistress – as long as doing so did not go against God’s word. In return, parents had the duty to raise their children in the Christian faith and to provide them with an honest profession. Heads of households also had the duty to ensure the morality and Christian enlightenment of their servants, and to provide them with adequate food and the agreed wages.

Marriage and sex

The household was built on marriage and was protected by its societal status. As mentioned above, marriage was a precondition for starting a family and establishing a household, but it was also the only legitimate framework for sexual relations. The post-Reformation legislation that had made extramarital sex a crime was incorporated into Danish law in 1683 and continued into the eighteenth century. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the punishment for having sex outside marriage was gradually reduced; by 1767 it was no longer necessary to confess publicly to the deed in church. From 1812, fines were no longer issued for a first or second offence involving extramarital sex. This decriminalisation of the unmarried was motivated particularly by the desire to alleviate some of the social shame associated with having children outside wedlock. It was not uncommon for an unmarried woman to conceal her pregnancy and kill the newborn child at birth, and lawmakers linked this widespread social problem to the punishments for extramarital sex and the shame of being pregnant outside marriage.

Prostitution was regulated as an independent offence only at the end of the eighteenth century, when people grew increasingly fearful of sexually transmitted disease. Until then, prostitution was regulated according to the laws for extramarital sexual relations; it was the sex outside marriage that was punished, irrespective of whether money was exchanged. In principle, the law applied equally to men and women, but in practice it was always easier for men to avoid the punishment and shame associated with extramarital sex. Rape and attempted rape were punishable by death but were difficult to prove, and if a woman accused a man of rape but could not prove it, she was instead punished for the sexual encounter that took place outside of wedlock.

The authority and duties of the manor owners

The manorial lords had rights and obligations in relation to all the residents on their estate, just like those the master of the household had in relation to his servants. Research in this area has primarily focused on the rights of manor owners, to some extent overlooking the significance of their obligations. The estate owner was the master of the manor and its land, and he therefore had the right to discipline his residents.

In an extension of the law on punishment in the household, the estate owner was responsible for ensuring that all criminal activity conducted on his lands was brought to court. In return, he had the right to collect the fines imposed on criminals. This did not mean that the owners of manors were keen to prosecute residents in an attempt to profit from their fines – in fact, quite the opposite. Prosecutions at the time were brought by private lawsuits, and the guilty party had to pay both the legal costs and a potential fine to the person who brought the case to court. If the guilty party was unable to pay, the legal bill was sent to the person who had filed the case – in this case the estate owner, who was then also unable to collect the fine. For this reason, manor owners were unlikely to file legal cases against poor residents provided the offence was sufficiently small.

If a manor was large enough, it formed its own jurisdiction, with a special court (birkeretten) where the owner had the right to appoint the judge. The estate owner also performed public duties on behalf of the absolute monarch. It was the owner’s responsibility to ensure that taxes on the manor were collected and paid to the king. If the peasants did not pay, the estate owner was liable for the amount. They also drafted soldiers and decided who should be recruited to the military. In addition, they administered matters of probate, which meant that it was the estate owner who calculated the value of a tenant farm upon the farmer’s death.

A number of manorial lords owned local churches, which had economic implications in the form of taxes. The owner of the church had the right to a share in the church tithe (a duty that the tenant farmers paid to the church), as well as access to the church’s capital and the ability to borrow from it in times of hardship. In return, owners were obliged to maintain the churches. Owning the local church also meant that the estate owner had the right to appoint the pastor, which meant that the pastor, who was also a local official, came to depend on the manorial lord.

In this way, the estate owner had both rights and duties. One of these duties was a general obligation to care for the sick and the poor on his land. In many cases, owners founded hospitals (poor houses) for the old and the poor and charitable funds for the deserving poor, which assured them a minimal level of alms and material assistance.

The poor and the destitute

The way in which society dealt with the poor and the sick changed during the eighteenth century. The first major legislation on poor relief in this period was issued in 1708. Since the Reformation, the so-called ‘deserving poor’ had been granted permission to beg. Begging now became completely forbidden, and the ‘deserving poor’ were defined as belonging to one of the following three categories: (1) the old and the sick, who were unable to work in order to sustain their existence; (2) orphans who were too young to work; and (3) people who were able to work, but not enough to support themselves and their families.

Poor people who did not fall into one of these categories were classed as the ‘undeserving poor’; in other words, they were able to work in order to sustain their existence but, for immoral reasons such as laziness or alcohol dependence, constituted a burden to society. The undeserving poor were not supported, but instead put to work: at the local workhouses in the towns, at the royal fortresses and building sites, in one of the workhouses (manufakturhuse) in Copenhagen or in one of the three workhouses that were specially built for this purpose during the eighteenth century – on the island of Møn in 1737, in Viborg in 1739 and in Odense in 1752. It was not possible to end the practice of begging, but serious efforts were made to combat it.

The deserving poor were deemed worthy of support. They could turn to the pastor, who was in charge of the poor fund. This was financed through voluntary contributions to the Church; through a Church tax, although this only represented a minimal source of funding; and through certain fines that went to the poor of the parish. In practice, many of the poor sought relief by going from farm to farm, where they were given food and lodging for a set number of days determined by the pastor. Older parents often took turns staying in the households of their adult children. The poor could also receive minimal support in the form of food and fuel. The elderly and orphaned children were placed in the household that bid the most for them, in return for their labour. When a new generation took over a household, an agreement was often reached for elderly people to remain in the house and be supported by the new master.

Poverty commissions and hospitals

The poor laws were revised again around 1800. A new law for Copenhagen was passed in 1799, for the ordinary towns in 1802 and for the rural parishes in 1803. A poverty commission was established in every parish, with the pastor as a permanent member and often as the chair, but also with places for the most industrious burghers and tenant farmers. The poor were still divided into the same three categories as in the 1708 law, and they still needed to report to the pastor for help. There is little reason to believe that the local poverty commissions were particularly generous regarding whom they helped. Unlike before, however, burghers and tenant farmers were now involved in the administration of social matters which had previously been the sole responsibility of authority figures such as the pastor or the estate owner. Funding for poor relief was now raised mainly from tax revenue rather than from voluntary contributions.

The sick were often covered by the same legislation as the poor, but there were also changes in this regard. At the beginning of the period, a ‘hospital’ was simply a place in which the sick and the poor were cared for under the same roof, but in the 1750s Frederik’s Hospital (Frederiks-hospitalet) was built in Copenhagen as the first to treat disease. At the same time, a maternity institution was founded in Copenhagen where unmarried women could give birth to their children anonymously, in an attempt to stem the many secret births.

Schoolchildren, the Sick and the Poor

In this film, Nina Javette Koefoed discusses the social reforms of the 18th century. The film is in Danish with English subtitles, and lasts about 11 minutes. Click 'CC' and choose 'English' or 'Danish' for subtitles.