1. The introduction and consolidation of absolute monarchy

With the introduction of absolute monarchy in 1660, all power was in principle concentrated in the monarch and thus lay in the hands of one person. Denmark was the only absolutist monarchy in Europe with its own written constitution, the King’s Code (Kongeloven), which was issued in 1665. Kongeloven set the framework for the most unrestricted form of absolutism, excluding the nobility, the burghers and the clergy from exercising power in representative forums. As soon as absolute royal rule was instituted, a major and sustained effort was made to consolidate the monopolisation of state power within the hereditary royal line of the House of Oldenburg. Shortly before 1660, the Crown’s territory had been reduced, with the loss of Skåne, Halland and Blekinge. The first absolutist kings made it their main political goal to re-conquer these regions from Sweden. In the years after 1660, the tax burden was thus drastically increased in order to finance the expansion of the army and navy, and the country was armed in an attempt to match Sweden.

The Lutheran Church, which had been integrated with the state after the Reformation in 1536, continued to play a crucial role for state administration and society alike. The absolute monarch was the head of the Lutheran state Church, and both the king and the Church saw it as one of their most important tasks to make people good Christians and obedient subjects. The religious education and unification of the population that had begun after the Reformation continued with greater force during absolutism, creating a foundation for a state that was unusually strong and centralised in a European context.

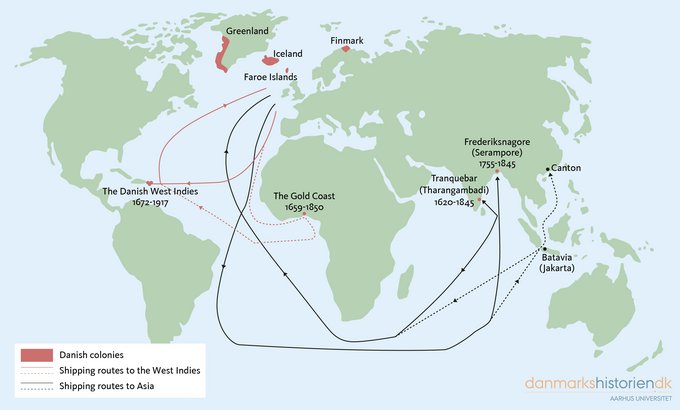

The Danish king led a composite ‘empire’ that became one of Europe’s colonial powers during the seventeenth century. Territories in India, Africa and the Caribbean provided the basis for Denmark to participate in advantageous trade and production in colonial areas.

The government gradually developed a considerable state capacity. This became visible through legislation and reforms, as well as within the judicial system, which consolidated the rule of law. Landowners had earlier served as intermediaries between the state and the peasants regarding tax and military service, but these responsibilities were completely taken over by the state after the end of the eighteenth century. In 1660, absolute monarchy was perceived as representing the power of God and the king was responsible to God, but this theory of the state had become outdated a century later. Instead, it was thought that the state should listen to public opinion and, to a certain extent, that the people should be consulted. From the mid-eighteenth century, Danish absolutism thus changed from being authoritarian to being ‘enlightened’ and influenced by public opinion.

Like other European countries, the Danish state of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries pursued a mercantilist economic policy aimed at developing the economy and improving conditions for trade and production. Improvements to the balance of trade were made by increasing exports and restricting imports, boosting the country’s tax revenues. For this purpose, large, organised ‘manufactories’ (manufakturer) were established, which mainly produced textile products for the military, and large-scale trade was conducted with the country’s own colonies.

Absolute rule lasted from 1660 until the introduction of constitutional monarchy with the constitution (Grundloven) of 1849. This module concludes, however, in 1814, with the surrender of Norway as part of the Treaty of Kiel. That year saw the end of the dual monarchy of Denmark-Norway and, more broadly, marked the end of Denmark’s role as a Nordic great power; only the kingdom of Denmark, the duchies Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg and the colonies remained. At the same time, the country was close to economic ruin after its participation in the Napoleonic Wars of 1807–1814, and absolute rule was being challenged.

The territories of the House of Oldenburg

In 1660, Frederik III’s territories consisted of the dual kingdom Denmark-Norway, and the Faroe Islands and Iceland in the north Atlantic. They also included Greenland, though it was only re-colonised in the 1720s after a long period of little to no contact. As in earlier periods, the duchies Schleswig and Holstein were also part of the conglomerate state. The legal status of these territories was complicated – they were divided between the parts ruled by the king and the parts ruled by dukes. In Schleswig, the king was both duke and, after 1721, also a vassal under the Danish Crown (in other words, he was his own vassal). In Holstein, he was a vassal under the German emperor, since Holstein was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The northernmost duchy, Schleswig, was bounded by the River Kongeå to the north and the Eider to the south and included the islands of Als, Ærø and Fehmarn, whilst Holstein lay between the Eider and the Elbe and included the areas of Stormarn and Dithmarschen. This composite kingdom included many peoples with different cultures and languages, but it was dynastically united under the House of Oldenburg, who ruled from the offices of the central administration on Slotsholmen (‘the castle islet’) in Copenhagen.

We do not have exact population figures for the second half of the seventeenth century, as the first real census was not completed until 1769. However, it has been estimated that around 1660 (that is, after the cession of the Skåne provinces), approximately 600,000 people lived in the kingdom of Denmark, approximately 450,000 in Norway and approximately 500,000 in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. In addition, around 20,000 people lived on the North Atlantic islands, which brought the total population to around 1.5 million.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the monarchy also acquired overseas colonies in the form of small territories in India, Africa and the Caribbean. A small trading colony was founded in Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) in southeast India in 1620, and beginning in 1659 a number of trade forts were established on the Gold Coast (Ghana) in western Africa. In the Caribbean – or the West Indies, as the area was called – colonies were also established on the islands of St Thomas, St John and St Croix in 1672, 1718 and 1733 respectively (today the US Virgin Islands). Denmark thus became a colonial power that participated in, among other things, the transatlantic slave trade. Despite the surrender of the Skåne provinces shortly before the introduction of absolutism, the Oldenburg monarchy therefore remained a medium-sized power in a European context and a significant power in northern Europe between 1660 and 1814, on a par with Sweden, which also included Finland until 1809.

Danish overseas colonies, North Atlantic monopoly trade areas and shipping routes between Denmark and the colonies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During the seventeenth century, Denmark became a colonial power, establishing the Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) trading station on the east coast of India in 1620 and a fort on the Gold Coast – in present-day Ghana – in 1659. Denmark also gained three West Indian islands in the Caribbean in 1672, 1718 and 1733 and the Frederiksnagore (Serampore) trading office in India from 1755. In the North Atlantic, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Finnmark and Greenland also belonged to the Danish-Norwegian Crown. © danmarkshistorien.dk

The existence of the Danish state had been under threat in the years immediately preceding 1660. A new threat appeared with the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815, with Denmark’s involvement stretching between 1807 and 1814). The Danish Crown joined the war on the side of the French emperor Napoleon, and therefore in opposition to Britain. It would be an understatement to say that the war did not work out in Denmark’s favour: it was only through the intervention of major powers that an amputated Danish state survived. Under the terms of the peace treaty signed in Kiel on 14 January 1814, Frederik VI was forced to cede the whole of Norway to the Swedish king. The Danish state was thus one of the biggest losers of the Napoleonic Wars in terms of land, and the country became a small state. In Norway, absolute monarchy was replaced by a constitution, signed at Eidsvoll on 17 May 1814, followed by a personal union with Sweden, which lasted until 1905. All this meant the end of the union between Denmark and Norway, which had been in place for over four hundred years. With the cession of Norway, the Danish kingdom was reduced in size from approximately 380,000 km2 to approximately 60,000 km2.