2. Royal politics

The written sources for Denmark’s history in the Viking Age are few and far between. The relatively few and short runic inscriptions only exceptionally mentioned persons or events that can be identified outside the inscription itself. Oral tradition in the form of skaldic verses was handed down for long enough to form the basis for the Icelandic royal sagas in the thirteenth century, among other texts, but these skaldic poems primarily concern Norwegian matters and do not reach back before the late ninth century.

The Franks and their neighbours

The main source for the earliest history of Denmark is therefore the annals that were written down at the court of the Frankish kingdom. The first time these writings mentioned an event related to Denmark was in 777. In that year, we are told, the Saxon prince Widukind sought refuge with the Danish king, Sigfred. The tribal name Danes had appeared during the Great Migration Period, and a Frankish source from the beginning of the sixth century mentioned the leader of an attack in northern France, Chlochilaicus, as a Danish king. But it is unclear which geographical area the term Dane referred to at this time, and in the intervening two hundred years the Danes were not mentioned.

When King Sigfred entered the stage in the year 777, it was first and foremost because until then Denmark had been a remote area that did not interest the Franks. We do not, for example, know anything about the events that lay behind the large-scale construction works at Kanhave, or on the Danevirke a generation earlier. By this time the continued expansion of the Franks had made the Saxons a major opponent, and thus the northern neighbours of the Saxons also began to acquire a strategic interest. Except for this, the Franks’ acquaintance with Scandinavia at this time was minimal.

Godfred’s wars

Shortly after the year 800, however, the Frankish sources became more expansive on the matter of Denmark. In 804, Charlemagne finally succeeded in subjugating the Saxons all the way to the border with Denmark. In the same year, the ‘king of the Danes’, Godfred, rallied a large army at the same border. In the following years Godfred repeatedly provoked his new neighbour: he sailed with a fleet of one hundred ships to Friesland and charged tribute, and he destroyed the trading post of Reric, near Wismar, leading the merchants from there to a new trading town on his own border, Hedeby. In 810 he allegedly challenged the Franks to war. The ageing Charlemagne set out on his last great campaign. But before it came to battle, Godfred was killed by his own men. The only casualty on the Frankish side was the emperor’s war elephant Abul Abaz, a gift from the Caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid. It did not survive the north German climate.

Godfred’s provocations were not trivial for the Franks. For six years, he posed a significant political problem. Various hints indicate that his kingdom was large. One of the grandees who took part in the conclusion of the peace after his death was ‘from Skåne’; on another occasion, Godfred’s successors were in southern Norway to fight a rebellion. In addition to Hedeby, the trading towns of Aarhus in Jutland and Kaupang in Norway were probably founded in Godfred’s time. The power he exercised, however, may well have been strengthened by fear of the new enemy. Throughout the Viking Age, the Danish kingdom and the Slavic Obotrites in Mecklenburg were referred to as the two key political players in the north. Though the kingdom was thus seen from the outside as a major political and geographical reality, it was at times ruled by more than one king. After Godfred’s death the Franks negotiated on several occasions with multiple kings, albeit from the same royal family. Reference was made at least twice in the chronicles to violent struggles for kingship.

Harald Klak and Ansgar’s mission

In the year 814, the year of Charlemagne’s death, his successor Louis the Pious was approached by a member of the Godfred family, later known as Harald Klak. He offered to recognise the emperor as overlord in return for military support. In the years that followed, the struggle to install Harald on the Danish throne received much attention in the Frankish sources. Despite two Frankish-supported campaigns in Jutland in 815 and 819, Harald became co-regent at best, along with some of Godfred’s descendants. In another attempt to win the monarchy, stronger means were adopted. In 823, Bishop Ebbo of Reims travelled to Denmark to preach Christianity. Three years later, in 826, Harald Klak was baptised with his entourage at the emperor’s court in Mainz, and then returned to Denmark with another evangelist, Ansgar, appointed by the emperor himself as a missionary bishop.

Over four decades, until his death in 865, Ansgar’s mission was a focal point in the relationship between the Frankish empire and the northern lands. The account of Ansgar’s life written by his successor Rimbert is an important – albeit subjective – source on conditions in Scandinavia. For a long time, Ansgar had limited access to Denmark, and concentrated his efforts in Birka, Sweden. After 850, once the threat of a Frankish takeover had disappeared, he returned to Denmark, and the king allowed him to build churches in Hedeby and Ribe. These may have served Christian foreigners in the trading towns as much as the newly converted. The mission and church building left a mark, however. A large number of early Christian graves have been found around what is now Ribe Cathedral, the oldest of which date to the ninth century. Finds of cross ornaments from this period also show that some Danes embraced the Christian faith.

Ansgar first established his mission station in Hamburg, but after a Viking attack in 845, his base moved to Bremen. Despite adversity and thanks to ingenious political manoeuvres, both the episcopate and the mission survived him. Ansgar was canonised shortly after his death, and became celebrated as the founder of Scandinavia’s Christianisation. Harald Klak’s case, on the other hand, remained unresolved. He remained a ruler who neither won Denmark nor made the Danes Christians.

The kingdom of Horik I

From 827, one of Godfred’s sons, Horik I, remained as the sole king. He continued to negotiate with the Franks, including on the supremacy of Friesland and the realm of the Obotrites, which, like his father, he regarded as his sphere of interest. The Franks suspected him of simultaneously being the mastermind behind occasional Viking attacks, which he denied. He seems to have made his mark on domestic politics, however. Archaeological traces in Hedeby show that it was during Horik’s reign that the trading town really grew. From the second quarter of the ninth century, both Hedeby and Ribe were organising production of a new type of coin, of the same format as Frankish coins, but with images that were modelled on Ribe’s older sceattas, or sometimes other motifs. This consistent currency reform in the two main trading towns must reflect a political initiative, of which Horik was the likely originator.

In 2018, a hoard of two hundred and fifty-eight coins was found at Damhus, just outside Ribe. All the coins belonged to an early type of the image-rich ‘Hedeby coins’, which, despite the name, were probably struck in Ribe in the first half of the ninth century. The coins have a face on the front and on the back a deer and snake, or in a few cases a ship motif. Although the motifs are the same, the use of a large number of different dies for the coins indicates a large minting and circulation in the trading town. Photo: Museum of Southwest Jutland

After the death of Louis the Pious in 840 the Frankish kingdom was riven by wars between his sons. Viking fleets were remarkably quick to arrive in Francia. The onslaught culminated in 845 with large-scale attacks on Paris and Hamburg, among other targets. Horik may initially have helped co-ordinate these attacks, which must have involved many warriors from his realm, but the expeditions quickly developed into operations under independent warlords, such as the chief Reginherus (Ragnar), who led the looting of Paris. In 854 a grandson of Godfred, Guttorm, whom Horik had exiled, returned to Denmark and claimed the monarchy. This led to a battle, in which Guttorm and Horik were killed along with several other members of the royal family.

An exceptional burial has been found at the southern access to Hedeby, with a chamber grave placed under a longship in a mound. The grave contained the skeletal remains of three men, as well as distinguished grave goods, including a splendid Frankish sword. The tomb is dated to the middle of the ninth century and is among the richest known in Viking-Age Scandinavia. Several identifications have been proposed for the deceased, including the exiled king Harald Klak, but also Hedeby’s town reeve, the king’s representative. A more likely candidate is probably Horik, or perhaps another member of the royal family whose history unfolded in and around Hedeby.

Viking expeditions

The only remaining member of the royal family was a child, who now became King Horik II. He was mentioned in a few sources during the years following, the last time in 864 when the pope wrote to him. In 873, envoys for two new kings – Sigfred and Halfdan, who seem to have shared the throne – sent delegates to Louis the German in Worms and subsequently Metz in southern Germany, making a peace agreement that allowed merchants to travel between the two kingdoms. After almost a hundred years of diplomacy, war and missions, relations between the Frankish empire and Denmark were thus resolved in a trade agreement.

After this, owing to internal strife, division and civil wars, Frankish sources on the relationship with Denmark and conditions there became scarce. Meanwhile, there is no shortage of Frankish, Anglo-Saxon and Irish sources about the Norse chieftains who at this time were leading large fleets and armies abroad. These included Halfdan, who conquered Northumberland in 876; Guthrum, who established himself in East Anglia in 878; Sigfred, who led a large army against Paris in 885; Rollo, who was endowed with land in Normandy in 911 and became the ancestor of dukes of Normandy; and Rurik, who established himself at Novgorod in 862. And more besides.

Some of these sea kings, and others, have been associated with the ruling family or families in Denmark. Names might point in that direction, but it is rarely possible to follow the connections beyond conjecture. Many warriors from Scandinavia must have taken part in the great Viking expeditions in the second half of the ninth century. Other Scandinavians set out to settle in Iceland from around 870, or in other settlement areas in the east and west. Place names and archaeological finds show that thousands of Scandinavian immigrants landed in the British Isles in particular during the Viking Age.

These expeditions also had great significance at home, as evidenced by the numerous finds of silver hoards from this time. The contents might be Islamic coins, payment rings from the east, or coins and jewellery sourced from western Europe. This influx of wealth may in some cases have helped to destabilise power relations: the death of Horik I at the hand of a successful returning exile may be one example. But at the same time, the option to send ambitious princes and warriors out on expeditions may have put a damper on domestic conflicts.

Travellers in Denmark in the 890s

Regardless of the difficulties of tracing a coherent history, we can state that the Danish kingdom continued to be perceived as a political fact. This is demonstrated in two short travelogues preserved in an English manuscript from the 890s. One traveller, Wulfstan, sailed from Hedeby to the trading town of Truso in present-day Poland and then continued further east. Sailing with the Slavic lands to the starboard side, he passed ‘Langeland and Lolland and Falster and Skåne’, and reported that ‘these lands all belong to Denmark’. Bornholm, he wrote ‘has their own king’, while Blekinge, Möre, Öland and Gotland ‘belong to the Swedes’.

The second account, reported by a chieftain named Ohthere from Hålogaland in northern Norway, described a voyage to ‘the port which is called Hedeby [‘heath-settlement’]’, which ‘stands between the Wends and Saxons and Angol [people from the Angeln peninsula] and belongs to the Danes’. During the voyage, Ohthere had to his port side first ‘Denmark’ and later ‘the islands that belong to Denmark’, while to starboard he passed ‘Jutland and Sillende and many islands’. Ohthere’s description distinguished between two population groups: ‘southern Danes’ in Jutland and ‘Sillende’ (southern Jutland) and ‘northern Danes’ on the islands and in Skåne. Since Jutland and Sillende were also described as part of Denmark elsewhere in the text, these accounts thus outlined a realm that included all the territories that were later, in the Middle Ages, considered parts of Denmark.

But there may well have been more than one regnant king in the kingdom at any one time. Over the course of the ninth century, the Danish kingdom was shared time and again between several heirs – as was the custom in other European kingdoms. It is also possible that different parts of the country might have appointed different kings, as happened several times in Denmark’s Middle Ages. At Ladby near Kerteminde on Fyn, a monumental ship grave under a mound was built around 925, the only known grave of this kind in present-day Denmark. The ship, 22 metres long, had housed a funeral rite involving eleven sacrificed horses and the remains of very rich, albeit plundered, burial equipment. It is hard to imagine a funeral of that nature being instituted for anyone of less than royal status, even if his name and deeds remain unknown.

Asfrid’s kings

When the historian Adam of Bremen made an attempt to compile an overview of Danish kings around 1070, he identified a number of names from around the year 900. He admitted, however, that he was unable to determine whether all had followed one after the other, or whether some had reigned simultaneously. Twenty-first century historians have not come much closer.

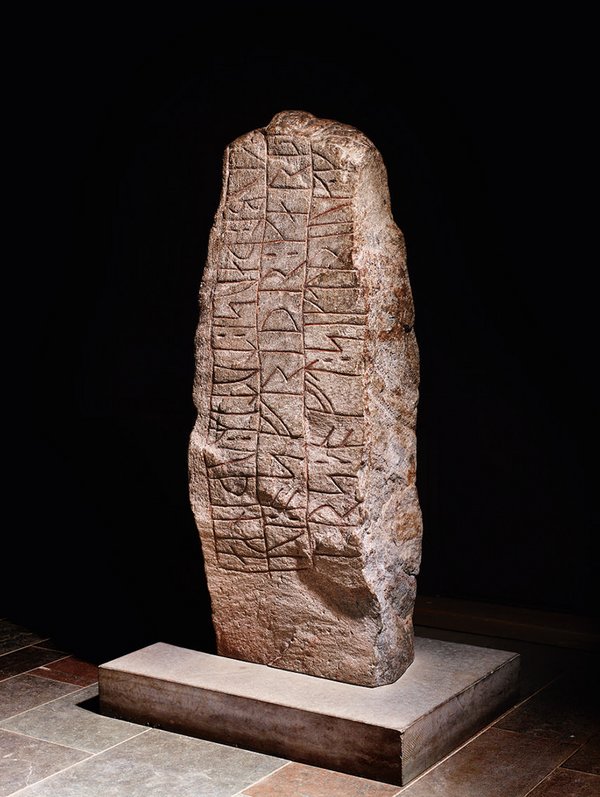

Two rune stones at Hedeby – Haddeby stone 4 and the almost-identical Haddeby stone 2 – were erected by ‘Asfrid, Odinkar’s daughter’ in memory of ‘King Sigtryg, her son and Gnupa’s’. Sigtryg and Gnupa were also mentioned by Adam of Bremen, who claimed that Gnupa was the son of an otherwise unknown king, Olav, who had come from Sweden and conquered the Danish kingdom. This has previously been interpreted as implying that Olav, Gnupa and Sigtryg represent a Swedish dynasty that had conquered Hedeby and possibly other parts of Denmark. Various linguistic-historical and runological arguments have been put forward in support of the theory, but conclusions are indecisive.

Haddeby stone 4, erected at Hedeby. The inscription reads: ‘Ásfríðr, Óðinkárr’s daughter, made this monument in memory of King Sigtryggr, her son and Gnúpa’s. Gormr carved the runes’. In the texts on the two rune stones Asfrid erected at Hedeby, she takes at least as much attention as the two kings she honours – her husband and her son. This and other examples show how women could occupy a prominent place in Viking- Age politics. Photo: National Musem of Denmark

We still do not know the provenance of Asfrid’s male family members, or whether they were kings throughout Denmark. Judging by the emphasis in her two runic monuments, Astrid herself may very well be part of the answer, alongside her family relationships. Other women were also capable of making a strong mark in the policy of the leading families at this time. One leading female figure erected two monuments to two successive husbands in different parts of Denmark: first, an impressive rune stone in memory of her first husband Gunulf, at Tryggevælde, Sjælland, then later a still more impressive monument with burial mound, ship setting and rune stone commemorating a second husband, Alle, at Glavendrup, Fyn. At the Sjælland site, this woman proudly named herself ‘Ragnhild, Ulf ’s sister’, in the knowledge that this was a name that was known. We do not know about her brother Ulf, whose name was apparently more important than that of her parents. But Ragnhild herself must have been a figure of comparable significance to Asfrid.

The Saxon raids

In the year 934, the annals of the monastery of Corvey in present-day northern Germany recorded briefly how the German King Henry I (the Fowler) subjugated the Danes. This is the first mention in the sources since the time of Louis the Pious of an attack on Denmark from the south. The timing was not accidental: after the final collapse of the Frankish empire in the early 900s, the Saxon Duke Henry had united the East Frankish lands. During the 920s, he began to amass military strength against his neighbours.

Adam of Bremen later believed that the king who had encountered his overlord was Gorm, the founder of a new royal dynasty that would eventually come to Christianise the Danish kingdom. That reconstruction fits conspicuously well with the moral of Adam’s tale of a royal family that recognised the East Franks as their masters. The chronicler Widukind of Corvey, writing in the 960s, claimed, however, that it was ‘Chnuba’ (Gnupa) who was defeated. That identification fits better with the events as we can discern them, and, if accepted, provides a date for Gnupa’s reign.

Widukind claimed that Henry not only defeated the Danish king, but also imposed taxes on him and made him receive the baptism. If this is the truth, the defeat can hardly have boosted Gnupa’s political standing. The fact that Queen Asfrid not only survived Gnupa but also raised rune stones in memory of her son Sigtryg may suggest similarly rapid political changes in Denmark after Henry’s campaign.

Gorm and Jelling

In the list of Danish kings learned at school by generations of Danish children, Gorm the Old comes first, because he initiated a series of rulers whose kinship to their predecessors is known. But Gorm’s own ancestors remain unknown. All that we know of Gorm’s family is found in the inscriptions on two rune stones which he and his son Harald erected at Jelling. The smaller of these was a monument in traditional style, not significantly different from the rune stones erected by other great men in Jutland at the same time. It was raised by ‘King Gorm’ in memory of his wife Thyra; it also mentioned other ‘monuments’ erected in her memory. The second and far more extravagant stone was erected by ‘King Harald’ in memory of ‘Gorm, his father, and Thyra, his mother’. The family ties are thus confirmed.

Medieval historians knew the Jelling monuments, and tried to the best of their abilities to fill the gaps in the history they reflected. The earliest of these sources, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum; in English ‘Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg’ by Adam of Bremen, said that Gorm came from ‘Nortmannia’, which may have meant either Norway or Normandy. Others pointed to England, where several prominent Scandinavians with the name Guthrum/Gorm were known in the tenth century. Much of what later written sources said about Gorm appears to be legend. Common to all is that he was perceived as a newcomer; no sources linked him to older kings. This is in line with the inscription on his own rune stone, where, unlike other rune stone patrons like Asfrid or Ragnhild, and his son Harald, he did not name his family or parents.

Up to the mid-tenth century, Jelling was an unremarkable settlement close to the old main road through Jutland. But from the 950s, and especially a few decades later, it became the arena for an exceptional series of monuments to Gorm’s family. Only in recent years have we gained a better understanding of the ‘monuments’ for Thyra mentioned on Gorm’s rune stone. The oldest sections of the Jelling monuments consist of a ship setting nearly 360 metres long, with the northernmost of two huge mounds at its centre. The mound itself contained a large chamber grave, built of timber felled in the winter of 858/859. It was probably built as a grave for Gorm, Thyra or both of them. Gorm may also have commissioned some monumental constructions elsewhere. The trading towns of Hedeby, Ribe and Aarhus – unfortified in earlier times – were all surrounded by large earthen ramparts in the first half of the tenth century. Gorm is the most obvious candidate for the instigator of these large, seemingly co-ordinated defence works.

The struggle over Thyra

We know nothing about Thyra’s origins, either. Two hundred years after her life, the chronicler Saxo thought she was an English princess. The Icelandic sagas said that she was the daughter of a Jutland king named Harald – a name that was indeed passed on to several of her descendants and had been borne by at least three members of the ninth-century royal family. But we do know that Thyra’s significance for kings Gorm and Harald was unusual. While women erecting rune stones to male relatives seems not to have been uncommon, the reverse – stones erected by men in memory of women – was rare.

All the more unusual is the fact that at least two other stones in Central Jutland, in addition to the Jelling stones, were erected in memory of an individual named Thyra, one of whom is even called ‘queen’. These are the stone at Læborg, erected by ‘Rafnunga-Tōfi’ in memory of ‘Thyra, his queen’, and the stone from Bække, the inscription of which states that ‘Rafnunga-Tōfi and Fundinn and Gnypli, these three made Thyra’s mound’. It has been speculated that Rafnunga-Tōfi was a competing contender for the kingship who married Thyra after Gorm’s death, but this theory entails many contradictions – among others, that Gorm’s stone for Thyra would have been a forgery. It is of course possible that the Thyra of Rafnunga-Tōfi’s stone was a completely different person from Gorm’s Thyra, but if so there were two almost simultaneous ‘queens’ with the same name, both of whom received very distinctive grave monuments.

A possible narrative which does not contradict the sources runs as follows. After Gnupa’s defeat in 934, the magnates expelled or killed him and his son Sigtryg and elected a new king, Gorm. For purposes of legitimacy, Gorm married a woman from a leading family with roots in the ancient line – Thyra. After her death, Thyra’s relatives, Tōfi, Funden and Gnyple, used grave monuments to state their claims in competition with her widowed husband, Gorm, and their son Harald. Such a reconstruction is speculative, but it respects the sources we know today.

‘Harald who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway’

Harald, who later acquired the epithet Bluetooth, was the first king in Danish history to have left an account of his deeds. This he did with his inscription on the great Jelling stone:

Harald who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.

Harald’s staking of his claim has not made his reign any less controversial. The adoption of Christianity in Denmark made him a veritable saint for some medieval historians, but for others, he was the loser in power struggles he had not chosen. Archaeology has revealed a third, and very different, history of events not mentioned in the written sources.

That Harald ‘won for himself all of Denmark’ has, in recent times, often been interpreted to mean that he united the kingdom. But that is not what the inscription says. Other kings before and after Harald had won kingship in competition with other candidates. Horik I in 800, Svend Estridsen in the mid-eleventh century and Valdemar the Great in the mid-twelfth century all ‘won’ Denmark. Harald, like them, must have faced challengers. The result, however, was that he won kingship not only in Denmark but also in Norway, where Håkon Jarl recognised Harald as his overlord around 970.

Harald probably also had an active policy in the Baltic region, as some sources suggest. The fairytale-themed Jomsviking saga, from around 1200, provided many generations with colourful stories about this, but it was probably largely fabricated as a counterpart to the Norwegian kings’ sagas. On the other hand, we know from a rune stone erected in Sønder Vissing in central Jutland that Harald was married to a daughter of the Obotrite prince Mistivoj, who was called Tove. This was surely part of an alliance with the strong political entity south of the Baltic.

The Christianisation of the Danes

Early in his reign, Harald Bluetooth became involved in a high-stakes power game with Henry I’s son and successor, Otto the Great, who was crowned Holy Roman emperor in 962. A contemporary chronicler, Widukind of Corvey, wrote that rebels in northern Germany tried to bring Harald into an alliance against Otto, but Harald refused. Instead, according to Widukind, he decided shortly afterwards to receive baptism from a priest, Poppo. It has been argued that Poppo was sent by the archbishop of Cologne, who was Otto’s brother and governor. In other words, there is a high probability that great-power politics was behind Harald’s decision. But contrary to what is often written, this may not have been a decision made under pressure.

One hundred years later, Adam of Bremen reported that Harald had been forced to convert to Christianity after his defeat to Otto the Great, who had led a victorious expedition to Denmark. Had that been the case, the event would certainly have been celebrated in Widukind’s chronicle, which was almost a tribute to Otto. On the contrary, Widukind, in strikingly cautious terms, avoided giving the emperor direct credit for Harald’s baptism. In the first half of the 960s, the newly crowned German and Roman emperor was under heavy pressure from the northern rebellion. It is therefore likely that conditions for the recognition of Harald’s new Christian realm were favourable.

There is little to suggest that a church organisation was established during Harald’s reign, or that Ansgar’s old archbishopric of Hamburg-Bremen came to play a major role. On several occasions in the tenth century the bishops of Schleswig, Ribe, Aarhus and Odense were mentioned in connection with the archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen. In 965, the emperor even issued them a letter of privilege – apparently in recognition of Harald’s conversion. Closer studies have shown, however, that the bishops in question probably served the archbishop. It is unknown whether they had contact with their nominal dioceses.

Harald’s pronouncements – both in the inscription on the great Jelling stone and on his coins, which from the 970s bore a cross motif – did, however, emphasise that the conversion of the Danes was meant seriously. The Jelling stone also fixed the visual representation of Christianity in another sense. It was richly decorated, and very different in form from all earlier rune stones. The inscription was placed in hori zontal bands, as in a book manuscript, and the images were carved in relief – a large animal entwined with a serpent, and Christ, without a cross but with outstretched arms and a halo. Both images became closely associated with Christianity in the Scandinavian art of the late Viking and Early Middle Ages.

The great Jelling stone. The inscription begins on the broad side with the majority of the text: ‘King Haraldr ordered these kumbls made in memory of Gormr, his father, and in memory of Thyra, his mother. That Haraldr who won for himself all of Denmark’. It continues on the side, under the great beast and the serpent: ‘and Norway’, and on the reverse, under the image of Christ: ‘and made the Danes Christian’. The monumental size of the stone and its decoration with images and intertwined ornaments were radically new compared to older rune monuments. In this way, the stone united traditional and new styles in its inscription and form. Photo: Roberto Fortuna, National Museum of Denmark

Harald Bluetooth’s battles and monuments

Archaeology documents that Harald was on the offensive in the 960s. Around 968, the Danevirke border rampart was strengthened with a large extension, and for the first time, the rampart around the trading town of Hedeby was connected to the fortifications. The latter had hitherto been in a border zone, as described in Ohthere’s travelogue in the 890s. Now it was demonstratively incorporated into Harald’s kingdom. Around the same time, Harald expanded the monuments in Jelling with a second grand mound and a giant palisade encircling all of Gorm’s and his own monuments. These were the first in a series of monumental constructions that distinguished Harald’s reign from that of previous Danish kings.

Politically, the winds changed for Denmark with the death of Otto the Great in 973. His young successor, Otto II, began his reign by settling the dispute with the northern Saxon rebels, and in 974 he carried out a campaign against the Danes, possibly provoked by a previous offensive by Harald. This crisis may have been the cue for Harald’s next, and very unusual, project. A group of large circular fortresses was built, the exact purpose of which is still debated. The group is named after the first to be discovered: the Trelleborg-type fortresses. Two of these fortresses are known in Jutland (Fyrkat near Hobro and Aggersborg by the Limfjord), one on Fyn (Nonnebakken in Odense), two on Sjælland (Trelleborg near Slagelse and Borgring near Køge) and two in Skåne, which were probably part of the same defensive network (Borgeby near Lund and a fortress in the town of Trelleborg). At approximately the same time, a wooden bridge, more than 700 metres long and five metres wide, was built over a river valley at Ravning, south of Jelling. All the fortresses were more than 100 metres in diameter and – with the exception of Trelleborg in Skåne – laid out with careful geometric accuracy. Two of the fortresses have been dated by tree ring dates from timbers: Fyrkat to around 975, Trelleborg to 980/981.

The discovery of the ring fortresses was one of the greatest surprises in the modern conceptualisation of the Viking Age. This co-ordinated initiative across regions revealed a level of organisation that had not previously been attributed to a king of this period in Denmark. The fortresses were obviously symbols of power, but they were also real defences, which may have served both as the king’s power bases and as protection against foreign enemies. They were abandoned, and in some cases destroyed, after a few years, perhaps when the threat from the southern border disappeared with Otto II’s death in 983. Their significance, like that of many other military installations in history, was short-lived. Over time they were forgotten.

Aerial photo of Trelleborg, near Slagelse. The five large ring fortresses from Harald Bluetooth’s time in present-day Denmark are all laid out according to the same strict geometric pattern. They had a precise, circular shape, and four symmetrically arranged gates. Two fortresses in Skåne were built according to a similar model. At least three of the fortresses had a system of large wooden buildings within. Trelleborg, to judge by the finds, was the most intensively used of the sites and was rebuilt after a fire with wooden buildings outside the main rampart, behind a small outer rampart. Photo: Knud Erik Christensen

Other finds from Harald Bluetooth’s time demonstrate that his power was more than gesture, however. Though coins were in use in trading towns throughout the Viking Age, trade generally functioned using fragments of silver, traded by weight. Hoards from the time of Harald Bluetooth have been found in several parts of his kingdom, consisting almost exclusively of the king’s own coins. This suggests that the king managed to maintain a monetary system, and probably also a form of tax or duty system, at the same time as the ring fortresses were being built.

From rebellion to raids on England

Several written sources agree that Harald Bluetooth’s reign ended with a revolt led by his son, Sven, and that Harald died in exile somewhere among the Baltic Slavs. They disagree on the details. Where and when Harald died is not clear, though it was probably no later than 987. The cause of the unrest is also explained in various ways: opposition to Harald’s Christianity, anger over workloads imposed by the king or simply family strife.

Perhaps the clearest indication as to what happened is the new policy that was instituted under Sven, later nicknamed Forkbeard. Throughout Harald’s long reign, we know of no major Viking expeditions to England. This changed markedly in the year 991, when a large Viking army challenged the English at Maldon in Essex, some of whom allegedly wanted Sven to be their king. Much silver was used to buy a truce with the Viking army. In 994 Sven led a large fleet against England together with the later Norwegian king Olav Tryggvason. They were paid a booty, known as the Danegeld, of 16,000 pounds of silver for peace. The expeditions continued with varying strength until Sven was recognised king of England at the end of 1013, following another major attack. However, he only enjoyed the title for a few months, as he died in February 1014.

That Sven himself led several of these expeditions was unusual. In the past, large Viking armies had been led by ambitious chiefs or members of the royal family, not by ruling kings. This must mean that Sven’s position in Denmark was secure, as was his political situation in the Nordic countries. After Olav Tryggvason’s death in the year 1000, Sven was recognised as king in Norway, and in Sweden Olof Skötkonung paid him taxes (hence the name – ‘tax king’). This was a marked difference from Harald Bluetooth’s initiatives, which had focused on Denmark, and it is easy to see that Sven’s successful expeditions were likely to have been more popular with the Danish chieftains than Harald’s demands for labour for his grand monuments.

Unlike Harald’s reign, Sven’s time did not leave many great structures to be revealed by archaeology. At Hedeby, Sven raised a rune stone in memory of a member of his retinue, and a large wooden church was built early in his reign in Lund. He had coins minted in English style with a cross motif, but these were few compared to his father’s. Sven also brought several English bishops to Denmark; there is therefore little reason to believe Adam of Bremen when he portrayed him as an apostate. In other ways, he acted carefully as a traditional Scandinavian king. In this way, during his more than twenty-five-year reign, Sven Forkbeard made Denmark the political centre of gravity in Scandinavia and the North Sea region.

Cnut the Great

Immediately after Sven Forkbeard’s death, his son, Cnut, was proclaimed leader of the Danish army that was still in England. Cnut was not recognised by the English, who instead brought back the exiled king, Ethelred. Cnut had to flee with large parts of his army and returned to Denmark, where the kingship had meanwhile passed to his brother, Harald. Cnut then raised a new army. Many warriors from all over Scandinavia were ready for the riches and reputation that had flowed from Sven’s expeditions. In the autumn of 1015, Cnut returned to England. After a winter of complicated battles and negotiations, and the death of both Ethelred and his son Edmund, Cnut won royal power at the end of 1016. He also married Ethelred’s Queen Emma.

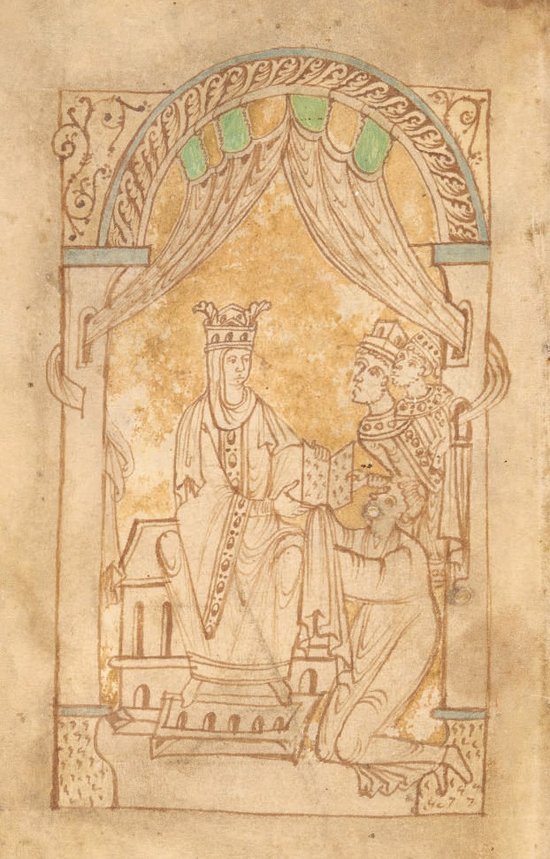

Queen Emma of Normandy, or Ælfgifu, to use her English name, was married to Ethelred, but after his death married the new king, Cnut the Great. She agreed that the couple’s joint children should have first right to the throne over her two sons with Ethelred. In this way, a conflict that could have threatened the lives of her first two sons was neutralised. Emma saw two of her sons crowned kings of England, and a daughter married to the German emperor. The image here comes from a tribute to her written around 1040, Encomium Emmae Reginae, an important source for Cnut the Great’s time. In the picture, Emma receives the document in the company of her sons Harthacnut, who was king of England and Denmark at the time, and Edward (the Confessor), who succeeded Harthacnut in England. Photo: British Library

Cnut was then able to disband most of his Scandinavian army with the largest peace payment ever seen. He set about organising his kingdom with trusted personnel – both English and Scandinavian supporters. When his brother died shortly afterwards, he travelled to Denmark in 1019 and was elected as the Danish king. Then followed a generation with a very special political and cultural constellation in Northern Europe, today often called the ‘North Sea empire’.

The North Sea empire

Cnut brought English mint masters to Denmark and was the first Danish king to have coins minted in multiple places around the country. Finds show that English potters also came to Denmark. Cnut ignored the archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen. Instead, English clergy were sent to Denmark, and he installed his own bishop in the newly established seat of Roskilde, which may have been intended as a future archbishopric for all of Denmark, formally subordinated to the archbishop of Canterbury. Both in England and in Denmark, an upper class emerged, with connections spanning both countries.

Cnut stayed in England for much of his reign, ruling by deputy in Denmark, first through Earl Ulf and later through his own son Harthacnut. But he stayed in Denmark for at least three long periods in the 1020s, and on those occasions took charge of many matters. His rule was not unchallenged. In 1026 he was forced to go to Denmark to defend his kingdom against a coalition of Swedish, Norwegian and Danish opponents. Although he titled himself king of England, Denmark, Norway and part of the Swedes during much of his reign, his power in Sweden was very limited. In Norway Cnut only really held power for a short period.

Seen from a broader perspective, however, Cnut was a ruler on a scale that no previous Danish king could match. This was evidenced in 1027 when he travelled to Rome, where he was received by the pope, and he was by the emperor’s side at the coronation of Conrad II.

Game of thrones

After Cnut’s death in 1035, his son, Harthacnut, was expected to succeed to the throne in England. Due to unrest, however, he could not leave Denmark, and another son of Cnut’s by an English aristocratic woman – Harald Harefoot – became king (r. 1035–1040). Harthacnut succeeded to the throne after him, but when he died in 1042 the English crown went to Ethelred’s son, Edward (the Confessor). Meanwhile, there was a struggle for power in Denmark. The king of Norway, Magnus the Good, won the crown, but was challenged by Cnut’s closest living male relative, his nephew Sven Estridsen. In 1047, Magnus died. Despite repeated attacks from his uncle and the successor to the Norwegian throne, Harald Hardrade, Sven became king of Denmark (r. 1047–1076).

Within Denmark, the 1040s was a time of unrest rather than foreign conquest. Under Sven and his sons, a period of almost eighty years followed without major expeditions from Denmark. As late as 1085, Sven’s son Cnut planned a major attack on England and William the Conqueror, but he had to cancel due to internal struggles. The time of the Viking fleets had passed.